Posted in: Comics, Recent Updates | Tagged:

Tough Minded Questions With Marc Guggenheim – Halcyon, Action Comics And More

Marc Guggenheim has a credit list that many envy. For TV he's written for The Practice, Law & Order, CSI: Miami and Brothers & Sisters. He co-created Eli Stone and is currently the producer and writer for ABC's No Ordinary Family.

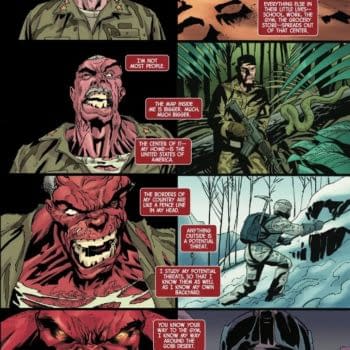

But twenty years ago, he was a Marvel intern. His comics writing credits since include Aquaman, Wolverine, Blade, The Flash, Young X-Men and his creator owned comic Resurrection. But this year, as he prepared to turn forty, he announced Collider Entertainment, a new publishing venture through Image Comics to bring Hollywood writers to comics, including his own book Utopian, then retitled Halcyon, written with Tara Butters, writer/producer for Law & Order SVU, Dollhouse and creator of Reaper, and drawn by Ryan Bodenheim.

Issue one of Halcyon came out this month and sold well. However orders for the second issue are due and might need a bit of pre-publication publicity. And this meant Marc putting his head in the jaws of Bleeding Cool. Not that, of course, he wouldn't bite back…

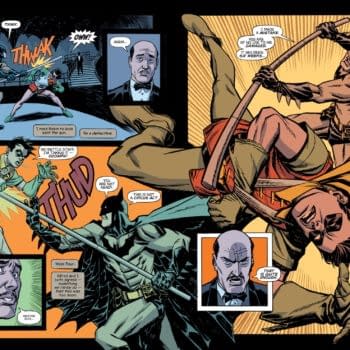

Rich: They say there are no original ideas left, just new and interesting ways to tell them. But Halcyon feels even more of a patchwork than usual. Super soldiers taking out insurgents and terrorists in their home countries feels like War Heroes. An extra-dimensional space where the same individual can compare notes with other dimensional equivalents of themselves, straight out of the Captain Britain Corps and recent Fantastic Four. And the world's greatest supervillain with the mindset of Golgoth from Empire, surrendering with a greater plan in mind straight out of Nemesis. Batman and Superman equivalents sleeping together from The Authority. And the whole "what happens when the superheroes win" seems ripped straight from Mark Gruenwald's Squadron Supreme or Alan Moore/Neil Gaiman's Marvelman/Miracleman. There have been lots of modern-world reinventions of the superhero over the last couple of decades, but based on the first issue, this doesn't seem to bring anything new to the party, indeed it doesn't seem to be as radical as its forefathers. Are you aware of the similarities, are they coincidental, and more importantly does it matter?

Marc: So you like the book is what you're saying… ;^)

Look, I think if you look hard enough, you can find similarities to anything — and clearly, you've looked pretty hard. But let me speak directly to the comparisons to Squadron and Miracleman because they go to the basic concept of Halcyon and they're also where your comparisons are the most, with respect, forced. In both Squadron and Miracleman, the heroes — with admittedly different degrees of totalitarianism — are actively trying to enforce a new world order on society; essentially forcing a utopia down their throats. Halcyon has as much relation to this concept as it does to the concept of, say, Deadpool — which is to say none at all.

In Halcyon, the heroes wake up one day to discover that through no fault nor action of their own, that crime and violence have stopped. It's not an event of their own creation. Rather, the story comes out of (a) the consequences this event has on their lives and (b) the mystery behind what caused it — because I don't think I'm spoiling anything to say that the world suddenly losing its capacity for crime and violence probably isn't a natural phenomenon. Bottom line, this is extremely different from Squadron and Miracleman because the heroes aren't the driving force behind the book's premise. Now, if you want to draw a comparison to a pre-existing work — and I can tell you do — then you're best off sticking with your Empire reference. Empire, as you know — and it's one of my favorite series — posed the question: What happens if the bad guy wins? Well, Halcyon poses the polar opposite question — what happen when the good guys win? — but I don't think it's any less original or innovative for asking the same question that Empire did, just rotated 180 degrees.

I find it ironic that among the works you referenced, you didn't mention Watchmen because if Halcyon has roots in any other comic, it's that. Let me explain: My wife — who's my co-writer on Halcyon and a professional writer in her own right — never read Watchmen. (Yeah, I don't know how I ended up marrying her, either.) We went to go see the movie version and her takeaway was, "That was interesting, but what really drew me in was the ending. I wanted to see what happened to those heroes in the post-utopian world Ozymandias created." And as we talked and riffed we both realized that there was an interesting story there: What happens to the heroes once obsolescence is imposed upon them? And, I'm sorry, but I've never seen that story told before. So I actually think the concept of Halcyon is really quite original. That having been said, let me be clear that Halcyon in no way aspires to be a sequel to or continuation of Watchmen. That'd be like me sitting down at a piano and thinking I could compose Eroica. Besides, I think the tone of Halcyon pretty clearly demonstrates that we're not aspiring to be Watchmen-like in any regard.

Now, you might feel like the characters who populate the book are unoriginal and to that charge I'd say… kinda. Obviously, a book like Halcyon — like Empire or The Authority or Nemesis — is playing with certain super-hero conventions and tropes. That's the whole point. For example, the high concept of Nemesis is Batman-as-a-bad-guy. For that book to work, there needs to be some similarities between Nemesis and Batman — or else it's just bad guy as bad guy. So the challenge with these kinds of post-modern or "meta" stories is to tweak the paradigms enough so that the characters are original but not so much so that the paradigms are unrecognizable. It's a very tricky business. That having been said, I think you'll find that in Halcyon, the characters of Enos, Triumph and Null are as original and non-paradigmatic characters as you're likely to find in a 21st Century comic.

Rich: For me the ending of Watchmen concentrated on Rorschach's diary, a single book with the potential to destroy Veidt's new reality entirely. Is there an equivalent in Halcyon?

Marc: Hmm. Trying to figure out how to answer without spoiling anything. Lemme put it this way: When you have a story that introduces a new status quo, one of the narrative questions that's instantly posed is whether that new reality will remain in place at the end of the story. In the case of Halcyon, one of the questions that readers, I'm sure, is "will the world stay perfect" at the end of the story? I think Tara and I have come up with an ending that will surprise and satisfy people — which is kinda tricky, when you think about it, given the binary nature of the question.

Rich: Well, here's an attempt to question a utopia. You've denied this but never really given any evidence against it that I can see – Collider feels like an imprint designed specifically to show pitches for films as a comic book, create a little astroturf movement and then make a more impressive pitch as a result, using the comics fanbase. It's worked for some – Cowboys & Aliens being the most prominent example, – but it does generate resentment from some readers, thinking they are just being used as a means to an end, and paying for the privilege. Can you explain how Collider is different? Feel free to use graphs.

Marc: I'm sorry, Rich, but this made me laugh. No evidence? How about the books themselves? I realize that The Mission hasn't been published yet and Halcyon is only one issue old, but the proof, as they say, is in the pudding.

Let's take a step back for a moment and consider the proper way to, as you say, "show pitches for films as a comic book." The best and most economic way to do that is to generate one issue — heck, just cover art will do in most cases — and shop it around to Hollywood. That issue, by the way, is best produced by spending all your money on that all-important cover and then finding some bargain basement — i.e., shitty — artist to fill 22 pages. (Sadly, you don't have to look very far for examples of what I'm talking about here.) Then you're off to, as you said, set up a pitch. First, I think you can tell from the quality of the art of both Halcyon and The Mission that we didn't go that route at all. We've gotten talent that's Marvel and DC quality, from the art to the coloring to even the graphic design. Everyone's mileage may vary, but I think the quality of the books — whether their your cup of tea or not — speaks for themselves.

Now… as hard as it may be for me, let's set the books themselves aside for a moment and consider the writers that Collider is involved with. Taking me out of the equation for a moment, do you think Jon and Erich Hoeber — who are writing The Mission for Collider/Image and who wrote the film adaptation of RED and the upcoming Battleship summer movie tentpole — need a comic to get a movie set up? These guys are as hot as magma in Hollywood right now. If they want to set up a pitch at one of the major studios, they pick up the phone and call their agent.

So why do they bother creating a comic?The answer to that question goes back three years, to when my partner, Alisa Tager, and I met. These days, you get two or more people who work in Hollywood (Alisa is a producer who's produced several films including Joss Whedon's Serenity) and they'll start carping on what's wrong with Hollywood. In the case of Alisa and I, we felt the problem was twofold. First, no one's generating original ideas — everything's getting recycled from some pre-existing property or material. Second, between the two of us, we knew A LOT of frustrated screenwriters who hungered for a creative outlet that allowed them to explore their own, original ideas. Many of them liked comics and were interested in writing comics, but didn't have the expertise and/or connections to do it — and that's where Alisa and I realized we could help. The Hoebers are a perfect example of our model in action: Take talented screenwriters who just want to create and give them the resources in which to do it across a variety of mediums, including comics.

Now, that's just the Hoebers, but the same goes for me and the other writers Collider is working with. Every writer we're developing with is an established talent in Hollywood. Even my wife — who's my collaborator on Halcyon, as I mentioned (ad nauseum, probably) — is an extremely established writer, having worked in television for over 12 years and created her own show (Reaper). Every writer we're working with is working in comics for one simple reason — the only reason, quite frankly, for a screenwriter to work in comics given how little it pays relative to Hollywood: the love of the game. (Brief digression: Halcyon and The Mission aren't the only two projects we're developing, but one of our cardinal rules is to never announce a comic until it's actually being drawn. I mention this because I feel it's another way Collider is different from other companies and imprints who's raison d'etre is to publish comics merely as proof of concept for would-be movies.) Specifically with respect to me, I would never want to squander whatever street cred I have in comics by being associated with badly-produced ones. That's why each Collider comic has to and will stand on its own as a quality read. Again, your mileage may vary, but we're not crapping these books out just to set up a Hollywood pitch which we could easily set up without the comic.

Oh, and by the by, we haven't taken Halcyon or The Mission out to the studio marketplace, so if our intent all along has been to leverage these comics into movies, we're doing a fairly lousy job of it, don't you think?

I hope I've satisfied your desire for evidence. I'm sorry I didn't use graphs.

Rich: Well, let's look at the comics publishing side, through Image. I was recently talking to Image publisher Eric Stephenson about how the comics system pays. There seems to be three main models right now, one in which the creators take all the risk, work for free and hope months down the line that money and possibly a film option will come through. A second where one of the creators works for free, mortgages their house the pay the other creator, and hopes no one forecloses. And a third where the publisher pays a page rate, takes the lions share of the rights and then spends years flogging it round studios hoping one hit will pay for all the flips. Which is Collider closer to, do you think – or does it have its own paradigm?

Marc: I'd say it has its own paradigm because we're experimenting with a variety of different ways to finance the books we're producing and we haven't settled upon one particular model. I'll tell you a story: Early on in our partnership, Alisa and I were trying to figure out the particulars of a certain writer's deal. Our concern was that if we offered this writer X, we were "setting a precedent" to offer X to subsequent writers. I went to sleep that night and thought about a couple of things. The first was that I was an attorney for five years and I'm sick to death of precedents. The second was that I'd been working for one of the major studios and their reason/excuse for doing things — or, more often, not doing things — was "to avoid setting a precedent" and I found it a remarkably limiting way to conduct business, particularly in a creative industry. So I called Alisa up the next morning and said, "What if Collider was a company without precedent? Each deal, each project and each writer will be approached differently because, hey, deals, projects and writers are all unique." That's a long-winded way of saying that Collider's paradigm is really a lack of paradigm. Each book is different and is treated as such and we haven't fixed our wagon to a particular model.

Rich: Are the media as unique? You have a long and wide history in television drama, both writing and producing. What are the main differences you find writing a scene for the comics medium and for the TV screen? How do you write action, dialogue, scene to scene transition differently?

Marc: Y'know, I get asked this question a lot and I never feel like I have a satisfactory answer. Part of that is because I don't have the greatest understanding of my own process. Like David E. Kelley once said, I don't spend a lot of time looking under the hood. That having been said, the dialogue scenes generally write the same. In comics, I'm really standing on Brian Bendis' shoulders, trying to write interesting, funny, compelling dialogue. Conveying emotion in a comic is a bit more difficult than in TV or film, but it can be done if you've created the right dramatic situation and you've got an artist who can "act."

Action's a trickier thing because one panel of a comic could blow out the budget of a TV show. In TV and film, visual effects houses bill out by the shot. That's what you pay for, so that obviously affects how you conceive of action sequences. Even if you're doing action that doesn't involve visual effects, you're still thinking in terms of budget. Even on a film — where you have a lot more money to play with than in television — there are budgetary concerns that you have to write to. It's not often in the first draft — in first drafts, I like not to limit myself — but the closer you get to production, the more realistic your action needs to become in terms of budgetary constraints.

Honestly, one can write a book on the difference between writing for comics and writing for television and writing for film — make me an offer! — so I never know where to begin or end with questions like this, to be honest. There are a million things to discuss and that number only grows once you start making distinctions between different types of comics and TV shows and films. But I don't want to leave you with the impression that there are a million differences. There are actual remarkable similarities, particularly between TV and comics — both of which utilize shared universes and long-running storylines. I've also found my comic book experience has been very helpful in my feature work — and I don't just mean in working on movies like Green Lantern and The Flash. For example, one of the narrative devices I've gotten used to using in comics — narration playing out over action — has found its way into a few of the films I've written lately. Bottom line, it's a give and take. In all three mediums, I'm telling a story — and, ironically, I've recently found myself telling stories about super-powered individuals in all three mediums. And each inform the other in terms of technique. Another example: The action sequences I script for No Ordinary Family — the TV show I'm presently consulting on — have been very well-informed from my feature film experience (much to the chagrin of NOF's producers, I'm sure).

Sorry if I'm rambling. You ask all these tough-minded questions and I whiff on the softball. But I really could go on forever, there's so much to talk about.

Rich: And what responsibilities do you delegate differently to others?

Marc: Well, in TV, I'm typically showrunning/Executive Producing and that requires a lot of delegation, a lesson I've learned the hard way. In the comics I write, I don't really delegate anything — except for some research, which my assistant Lindsey (hi, Lindsey!) helps me out with quite capably. For Collider, I'm aided and abetted by Alisa and we hired Aubrey Sitterson — who edited Blade back when he worked at Marvel — to edit and traffic our books ('cause lord knows I don't have that kinda time).

Rich: I was wondering if you adhered to the old Mort Weisinger, 210 written words on a page, 35 words a panel in a six panae page, no more than 25 words in a balloon standard for comics – and if any of that affects your screenwriting?

Marc: Well, I have to be upfront about my ignorance when I say… I didn't know there was such a rule. Has someone told Bendis? (grins) Seriously, this is news to me. I'm actually kinda curious to go back an look over some of my comics and see how much I've adhered to this by accident or instinct. I have my own rules that I try to adhere to to keep the pace going and a rein on the wordiness. I try extremely hard to limit the number of 6-panel pages I have in a book. For me, the ideal number — barring some action sequences — is 5 panels-per-page. I'm not fond of the look of 2-panel and 4-panel pages. 6-panel pages can look a bit cramped. So I find myself partial to 5-panel pages. As far as word balloons within a panel, it really depends — for me, at least — on the kind of "shot" that's being called for in that specific panel. For example, if there are two people in the panel instead of one, that affects the number of balloons in the panel. I'll generally do more words and more balloons if it's a "close-up" on one person. Their chance to speechify, if you will. Similarly, I try to keep the talking to a minimum if there's action going on. Unless, I'm writing Spider-Man, of course.

Speaking of Spider-Man, I just did a five-page story in Amazing Spider-Man #647 that pretty much breaks all these rules. I was going for a very Aaron Sorkin-like feel in the story — basically a conversation between Spidey and Flash Thompson — and there were A LOT of words and balloons, but I have to say that Graham Nolan, who drew it, and Joe Caramanga (who lettered it), really, really rose to the occasion.

As for screenwriting, that has its own rules, but my general approach — which is to internalize the rules, make them instinctual, then forget about 'em — is the same.

Rich: Well, you do have that experience. In terms of the amount of screen writing and comics writing experience in the respective industries, it's probably you and JMS right now.

Marc: Huh. I hadn't thought about that. Strange — lofty — company to be in.

Rich: Well, it was alleged at the time that you left Action Comics shortly after being appointed writer, when you discovered Superman wouldn't be in the book, only in the Superman comic. JMS denies that he insisted Superman only be in his book. How did you see it? And seeing the overwhelmingly positive critical reaction Paul Cornell has got with Lex Luthor's Action Comics, playing with Neil Gaiman's Death and the like, do you regret that decision at all?

Marc: Well, first let me say that I never had any direct dealings with Joe. Apart from a brief conversation with Dan DiDio, all of my Superman-related communications were with super-editor (and I mean that in every sense of the term) Matt Idelson. So I don't know if Joe passed down a mandate that Superman couldn't be in any book other than Superman, but by all accounts he's one of the more principled people in the business and I take him at his word — and, besides, such a mandate would be pretty unnecessary since, in my opinion, it would be pretty stupid to have two books where Supes is traveling the country. For one thing, it would've taken away from Joe's story. I also think — though you would have to ask them — that DC felt the same way. Having Superman in Action while "Grounded" was taking place was never a consideration in any of our minds.

That having been said — and I really should make this crystal clear — I was perfectly fine with being Superman-less for a time. In fact, I'd worked out a whole story that would lead up to Superman's triumphant return to Metropolis — in it's darkest hour, natch — that turned his absence into a virtue. But then, as these things often happen, discussions ensued and ideas evolved and the focus started to fall more on Lex and the story started to become more about Lex's quest for a Black Ring… and I realized that while the story had become extremely cool, it had also evolved itself out of my wheelhouse. Realizing this, I went to Matt and said I didn't think the Lex story fell within my skill-set anymore. Bottom line, I didn't want to write a story I didn't think I could knock out of the park — and certainly not on a book like Action Comics. So I suggested stepping aside and Matt was very gracious about it. Enter Paul Cornell, who seemed to have been genetically-engineered to write the Lex/Black Ring story, as he's proving every month on Action. (If you're "mates" with Paul, you should check with him on a photo to run with this interview — at SDCC, his wife took a great shot of us strangling each other.) So do I regret my decision? Not at all. I feel validated. Ask my wife — nothing makes me happier than being right. Plus, moving off of Action made me available for my current gig on Justice Society of America, which I'm having an absolute blast on. So it all works out.

Thank you Marc. Halcyon #1 is in comic shops now. Watch Bleeding Cool for a preview of issue 2 on the morning of Thanksgiving Day.

Photo by Caroline Symcox

Marc Guggenheim can be found at legalscribe.net and lilysara.com.