Posted in: Comics, Vintage Paper | Tagged: brave and bold, horatio alger, street and smith, the issue

THE ISSUE: The Brave and Bold Before The Brave and the Bold

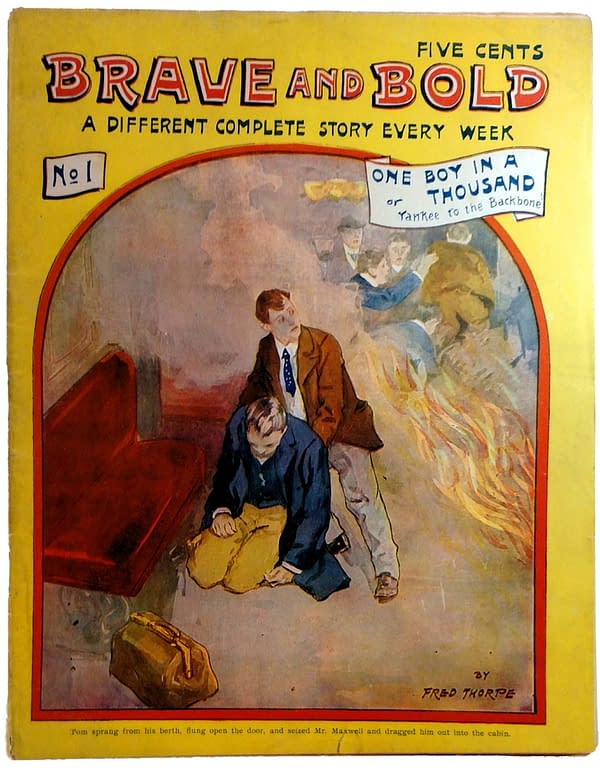

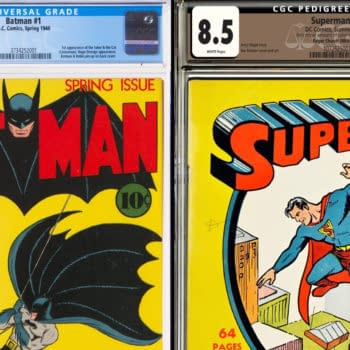

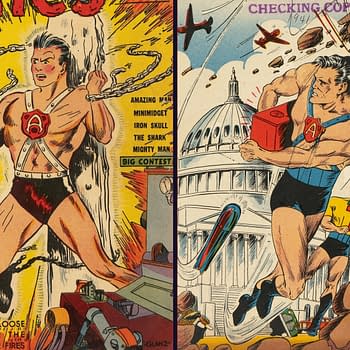

Most people reading this post will know The Brave and the Bold as a longtime DC Comics brand best remembered today for its association with Batman. That brand began with the series of that name which began in 1955, largely written and edited by Robert Kanigher to start with, and probably named by Kanigher as well. But our featured issue this time comes from several decades before that, and is the debut of a different Brave and Bold entirely. Brave and Bold #1 from publisher Street and Smith launched a 492 issue weekly series lasting from 1902 to 1911. As DC Comics writer, editor, and historian Mike Gold replied when I mentioned this matter in the Platinum Era Comic Books & Periodicals Facebook group, "Bob Kanigher was really good at… borrowing… old dime novel titles. Then again, he certainly was not alone in that."

The Brave and Bold Street and Smith title itself was borrowed from a Horatio Alger story which was first serialized in another Street and Smith title, New York Weekly in 1872. Many other well-known dime novel series titles were likewise based on Alger story titles — Work and Win, Do and Dare, Fame and Fortune (notably, a Frank Tousey nickel weekly which was eventually acquired by Street and Smith, becoming a pulp title that debuted their original version of The Shadow).

The Issue is a regular column about vintage comics and other vintage periodicals from throughout world history. The idea behind The Issue is simple: for each post, I'll choose something from my collection and talk about what's going on in it, and discuss the publishers and creators behind it. And essentially I'm just going to end up stepping through comics history one issue at a time. There is just one rule in The Issue: No recent stuff. Everything will be from before 1940, and most of it will be from before 1920.

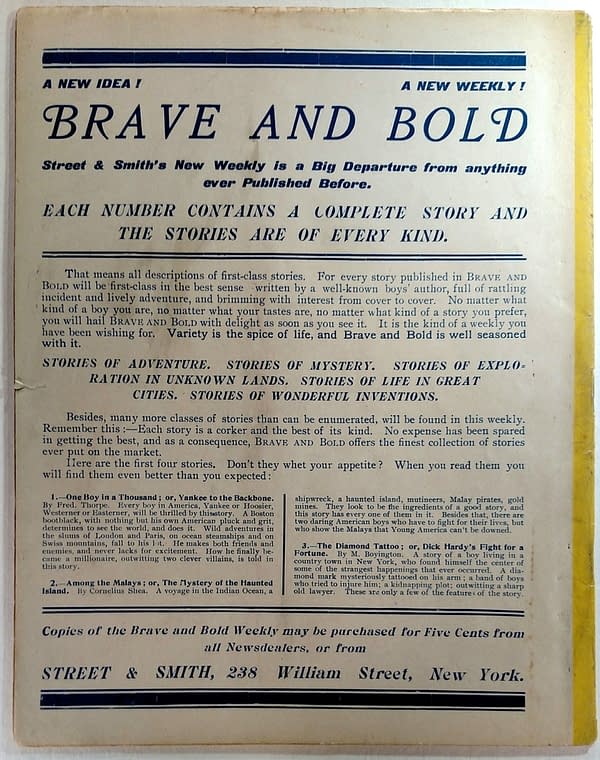

Reading the blurb on the back, you can see that it captures the spirit of the more famous comic book series that the title was inspired by as well: "Stories of Adventure. Stories of Mystery. Stories of Exploration in Unknown Lands. Stories of Life in Great Cities. Stories of Wonderful Inventions." That sounds pretty great, and as I have quite a few issues of this run, I can tell you that it is in fact a great series.

But I can't mention Alger without seeing red, and since a fair bit of scholarship on the subject chooses to sidestep this matter, and since… among many other terrible things… it is perhaps the canonical example of the cultural impact of bad history, let's go there: You probably know that the classic notion of the "Horatio Alger tale" has become synonymous with the notion that success comes from hard work and honesty (or to be more accurate to the original stories, hard work and honesty will bring you to the attention of a wealthy patron who will help make you a success). The Batman/Robin dynamic is often considered an example of the Horatio Alger type of story: A brave and capable young boy taken in by a man of wealth and means, who can help him achieve greatness.

Unfortunately, Alger's history as understood by the public at large was based on deliberate deception for nearly a century after his death, the actual story finally being documented in a singular piece of smart, stellar historical scholarship in the book The Lost Life of Horatio Alger, Jr. in 1985, by historian Gary Scharnhorst.

I should note that this is going to be a tough read which involves sexual assault, though I'm going to leave out plenty of details for reasons that will be obvious. In brief, here's what happened: In 1866, a group of parishioners from the Unitarian church in the village of Brewster, Massachusetts, threatened to prosecute Horatio Alger, Jr. to the fullest extent of the law if he remained in their town. Why? I'm going to quote a bit from Scharnhorst's book:

At first, unsure how best to break the news, [Horatio Alger, Jr.] said nothing of the brewing scandal. On March 19, he posted a letter "written in deep sadness" to the committee charged with investigating his conduct in Brewster, begging them to consider the shame his family would suffer if they chose to publicize his transgressions. Then, delaying no longer, he confessed to his father that he had been charged with pedophilia, engaging in sexual acts with boys in his congregation.

Scharnhorst goes on to outline the realities of much of the rest of Alger's life, after he'd fled to New York City and elsewhere. Noting that Alger very often "took in", "informally adapted", and otherwise lived or spent time with street boys, Scharnhorst also systematically demonstrates that many of the details of the life that Alger himself claimed to be living at the time are verifiably false. I'll leave that at that, except to note that this puts a sinister cast on the notion of the fictional "Horatio Alger tale", to put it mildly.

Moving beyond that and getting into how this history was covered up — and how unspeakably poor scholarship kept it from coming to light for so long — are likewise important to note here. In brief, upon his death, Alger's family burned all his letters, papers, etc that they had in their possession. They then commissioned a falsified biography of Alger. The biographer, Herbert R. Mayes, who would go on to become the editor of Good Housekeeping, a director of The Saturday Review, and president of major magazine publisher the McCall Corporation, would claim very late in his life that finding little available documentation to base the bio on, he chose to write… a parody. Yes, a parody, that he never expected to be taken seriously.

Most scholars have chosen to give Mayes a pass on this. I'll simply observe that I don't find his explanation remotely credible. The details of the fake bio were perpetuated in a couple of ways: 1) The Alger family is known to have threatened at least one scholar who may have attempted to seek out the real details. 2) Subsequent researchers and writers simply cribbed the Mayes book and passed it off as independent work. I think many historians and researchers will realize that (2) happens far more often than it should.

Although the Scharnhorst book is universally considered well-researched and accurate, and has been followed up by others with corroborating research, this matter remains little known. When I've brought it up to scholars in the area, it's largely met with shrugs and comments about separating the author from his work. While there are certainly cases where that's a legitimate point, the author's life and his work share such tragic commonality in this case, that I'm not sure it's possible here.

And beyond all of that, there's also this: Never be afraid to challenge any bit of history by doing your own research and forming your own conclusions. No matter how revered the subject, no matter how respected the authors who came before you. Don't be afraid to question or engage in civil debate with fellow historians. Or gracefully accept when you're wrong. That happens to everyone. People tend to strongly resist the notion of challenging such long-accepted, comfortable history, but it is incumbent on anyone who considers themselves a historian to seek out the true past.