Posted in: Comics, Recent Updates | Tagged: dark horse comics, matt kindt, mind mgmt, Past Aways

The Editor As Talent Scout And Taste-Maker – MIND MGMT's Brendan Wright In The Bleeding Cool Interview

It seems like 2014 was the year when I started noticing Brendan Wright's name on a lot of books I was reading from Dark Horse, though he'd been working on prominent books for the publisher for much longer. Like most people who read comics (let's face it), I seldom really paid much attention to the name of the editor inside the cover. In fact, I'd say I'm more familiar with the names of designers, another group who receive too little attention, than I am with editors. Since I am an editor myself, that's a particularly big blind spot which is, unfortunately, shared by comics culture.

Wright doesn't see it that way, though, and that's to his credit. He feels that a certain amount of invisibility goes along with the job, and that an editor's mark is made in the books that reach readers. So, not only is Wright deserving of a lot more attention, but he's incredibly humble as well. That does not make me feel any better about my oversights.

Wright was kind enough to join us today for an extensive interview about his career, the experience of working on MIND MGMT, and what being an Editor in comics has meant to him so far.

Brendan Wright: There is some anonymity if you work outside DC and Marvel, where the editor's role as long-term shepherd of a property often puts them in the spotlight while talent come in for shorter runs. That actually suits me just fine. I can see why that's an important part of the job if you oversee those types of projects, but I think outside that context, editors should be invisible, and I look at those editors who seek attention with some skepticism; if that's what you want, you probably got into the wrong profession. I work primarily on creator-owned books by talent that I've had long relationships with, either as an editor or as a fan, and I see my job as removing the obstacles between them and producing the kind of work I love. When I work with a particular creator whose work I know, my goal is to make the project I edit the purest version of what they do that anyone has published.

It's very gratifying when I meet people at cons and they know my name from the books or when someone tells me that the books together add up to some sort of editorial vision, but I'm fine with that being as much as people think about me.

BW: Thank you very much! I've actually been at Dark Horse since September 2008, starting as Assistant Editor to Diana Schutz. I became Associate Editor in 2012 and have been working independently since shortly after that, focused primarily on developing new projects. With the bump to Editor I'm looking further out on the schedule at larger programs and devoting more time to training assistants.

Dark Horse is my first paid gig in comics, but I was doing things in and around the scene for a little while before that. I sat on the Stumptown Comics Fest planning committee for a couple years, helping out with general logistics and promotion and running the portfolio review program one year. I took some comics-making classes from artist Jesse Reklaw at Portland Community College and comics theory classes from Diana at Portland State University, which is how we met. I also got to teach my own comics class at the high school level, which I was set to repeat before I was hired by Dark Horse. I loved teaching and still hope to fit that in again someday. Right before Dark Horse, I interned with Brett Warnock at Top Shelf, which exposed me to a lot of wonderful stuff, and I still have a relationship with them; the Top Shelf booth is one of my home bases at cons.

Before comics, I mostly bounced around, with freelance legal research as the closest thing to a constant, working on cases between other jobs. I also worked as a barista and a receptionist and tried my hand at film work, doing a little gripping and PAing for corporate films and stuff. I love film, but Portland didn't really feel like the place to do it.

BW: Oh, yeah. I read about comics as much as I read comics, easy, and comics history is an obsession. I love The Comics Journal's long-form interviews and books like Sean Howe's Marvel Comics: The Untold Story and Gerard Jones's Men of Tomorrow. Fred Van Lente and Ryan Dunlavey's Comic Book History of Comics is so readable and actually explains a few things that I'd read about a couple times before in ways that finally made me understand them. I'm looking forward to reading Jill Lepore's The Secret History of Wonder Woman. My reference shelf at work has some more encyclopedia-style reference books and old comics I like to look through for inspiration.

Related to that, I get very worked up about the history of the treatment of talent in this business, and I was as loud on the blog and on Facebook (but not yet Twitter; I only started using it this year, and am still terrible at it) as someone relatively unknown is capable of being about Alan Moore and Before Watchmen, the Kirby family's lawsuit against Marvel and the lack of compensation to comics writers and artists for insanely successful movies like The Avengers, and the lawsuit brought against DC and Warner Brothers by the Siegel family. That one in particular I think was just a tragic miscarriage of justice. I always think of the treatment of Siegel and Shuster as comics' original sin.

I get told I'm a bad nerd sometimes, because as much as I love comics, I'm not into a lot of the related fandoms. I don't play video games (though I find them fascinating), watch sci-fi TV shows or go the superhero movies, and I don't really have any fan culture merch outside of the comics themselves. But comics run deep for me, and I read all kinds of genres in comics that don't really interest me in books or movies; something about the medium just plugs me more directly into those stories. I nerd out about weird Marvel comics from the seventies, like Power Man or Howard the Duck, DC crime stuff from the eighties like Underworld and Thriller (and oh man I wish the 1st Issue Special issue of Lady Cop had become a series). Love and Rockets, Hate, The Invisibles, Hitman and Preacher, Jack Kirby's Fourth World books, and everything Osamu Tezuka have always meant a lot to me. I got into comics reading Batman, but I don't really follow superheroes anymore.

For the blog, originally I was just writing about the comics I was reading to get better at thinking about them and generate some writing samples, and the early interviews were with people I knew, having first met Jamie S. Rich when I job shadowed him for a day at Oni while in high school and Shannon Wheeler when he guest taught my comics-drawing class around the same time. I just wanted to know what people thought about comics; I interviewed my retailer, Floating World Comics' Jason Levian, and Brett Warnock, who I had interned with at Top Shelf. Interviewing Brian Michael Bendis was the first time I received much attention, especially after he reprinted the interview in Powers. Once I was working in comics full-time it got harder to then go home and write about them some more, but I've been thinking about it lately. Steve Gerber is a personal hero of mine, despite his flaws—but your heroes should have flaws, right?—and if I get the blog going again, which will require a lot of overhauling, I have a big Steve Gerber project I want to do.

BW: I got my degree at USC, which has a beautiful history in the film world and provided both amazing depth in film theory and astonishing resources for someone as only semi-talented at filmmaking as I was. I look back at the equipment and soundstages they willingly entrusted to me, and it doesn't seem quite real. I refer to that training a lot. You obviously have to keep the differences in film and comics in mind, but my background is in visual storytelling, which naturally comes in handy on a daily basis. There's also a ton of juggling that goes on when you're making a film, and that translates pretty well. I enjoyed directing, but I remember planning a short film I was going to shoot in Portland while I was still in LA, and somewhere in between talking to the people who were doing casting for me a thousand miles away and making sure the locations were close enough to each other to shoot in just a couple days, something clicked. This kind of project management, still creative but very much about logistics and making sure things work, really got me excited, and when I later decided to give comics a shot, that was one of the things that made it pretty clear editing was the right fit.

They also bang character and story structure into you, both of which are handled differently in comics than in film, but with tons of overlap. I sometimes feel like a fraud for not having an English degree, but film is actually excellent training for comics.

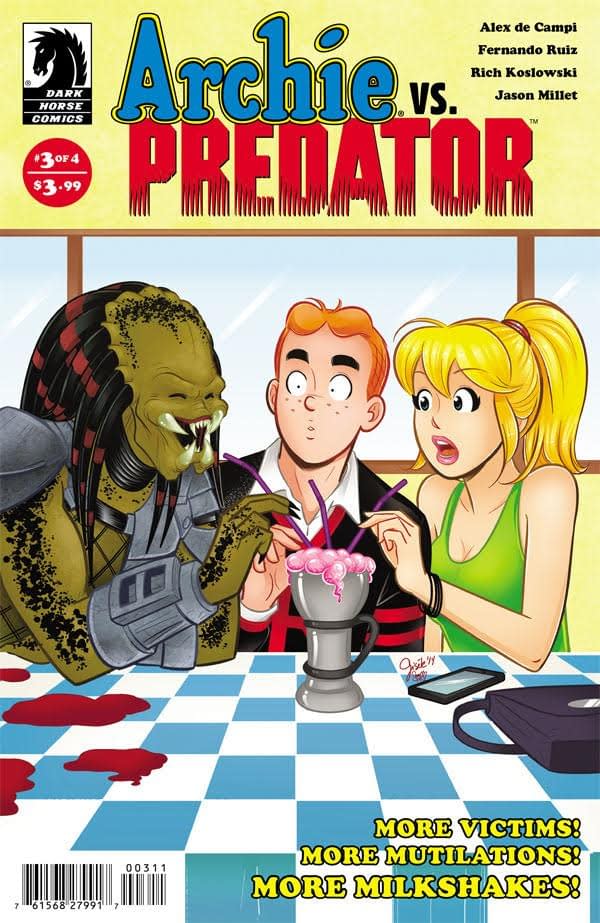

Beyond that, I refer to movies for visual ideas as much as I do comics, and I'm pretty comfortable talking about eras of movies in terms of developing aesthetics for books. My attraction to Alex de Campi's Grindhouse: Doors Open at Midnight comes as much from loving movies as from comics, and the movie poster pinups and the occasional movie recommendations the whole team writes have been so much fun.

BW: Oh man, it's been four years. I was first just assigned as the assistant on "the next Matt Kindt book," and then I got a Facebook message from Matt titled "mind mgmt?!" In it he said he'd heard I was assisting on his next book, but I had no idea why that was the subject line. A little later, Diana's schedule had required that I take over the series, and the next thing I saw were the scripts for the entire first arc, since Matt likes to write several scripts at a time when possible. It had little thumbnails of each page on it, so I had a pretty good idea right away of what volume 1 was going to look like, and while I gave a little feedback on both the script and art, it's not very different from that initial version I got. There were two endings, in case sales didn't allow us to go past issue #6, but fortunately we didn't need that other one.

From those first scripts, it was obvious that this wasn't like other comics series, and it was even pretty different from Matt's previous work. I loved the characters immediately, and reading the outline for the rest of the series, which was longer at that point, before Matt moved some things around and condensed some others, sucked me in with its story that is actually really simple on one level, but allowed him to hang so many new ways to use comics and so many unique characters on. The side text appeared when the art came in (it's never in the script) and that was a whole new experience. Truthfully, I've been lucky enough to be on a series where I get to be the first reader and experience all the same surprises everyone else does as much as I get to be the editor.

BW: If something looks weird, I just text Matt. If it's intentional he'll explain what I'm missing; if it's a mistake, he'll text back, "oh shit."

Beyond that, it's a lot of rereading, a lot of referring to old issues while reading new scripts. It's probably not all that different from how MIND MGMT's more devoted fans read the book. I just do it early and get to ask Matt what's going on. It does help to know where we're going, since Matt's had the ending in mind since the beginning. Matt also reread heavily before each of the final arcs, and my brilliant Assistant Editor Ian Tucker also gives each issue a pass and catches things I don't.

HMS: Have you ever used a magnifying glass to edit the annotations in the margins of MIND MGMT?

BW: I should have! I have 20/20 vision, but I've started to notice things far away getting a little blurrier, and squinting at those annotations are probably part of the reason.

HMS: In all seriousness, though, Matt Kindt has referred to you as a "conspirator" on the series, and it has occupied your mind for several years now. Now it's winding up, though some time ago Matt used to say there might be some more aspects of MIND MGMT once the original series was complete. What will you miss most about working consistently on the series?

BW: It's felt like a phase of my career ending. To whatever extent I am known in the industry, it is primarily through this series, and I have thought about it every day for four years now. Giving the last six scripts an initial read and edit when they came in all together was a pretty emotional evening, and finalizing each issue since then—we're about to send #35 to the printer—has been a small blow. That said, it was always meant to end, and I'm proud that it's ending exactly on Matt's terms exactly when he wanted it to. As much as anything else I have done as editor of MIND MGMT, I am proud of the hustling that I did to help those initial six issues sell well enough for us to go all the way.

I'll miss the characters—I love them very much—but I don't really have to miss much else. Matt and I have known what the followup series to MIND MGMT is for a couple years, and we're finally announcing it at San Diego this year. So when MIND MGMT finishes, we head right into the scripts of the new series, and I'm pretty confident that Matt's going to continue to come up with new ways to tell stories in comics.

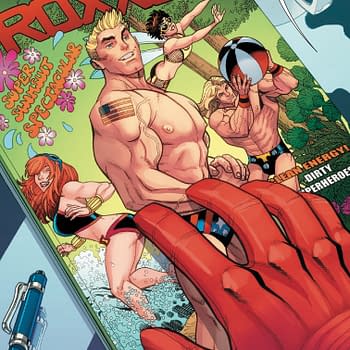

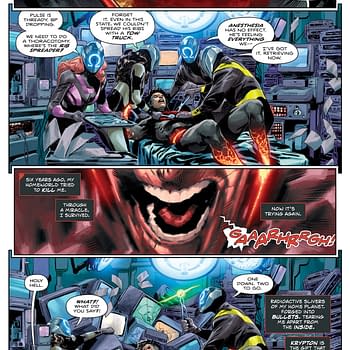

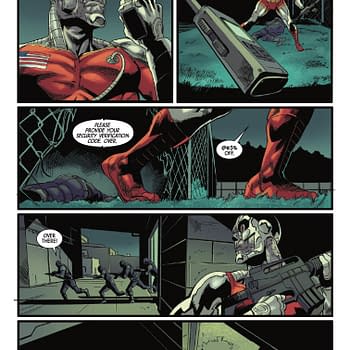

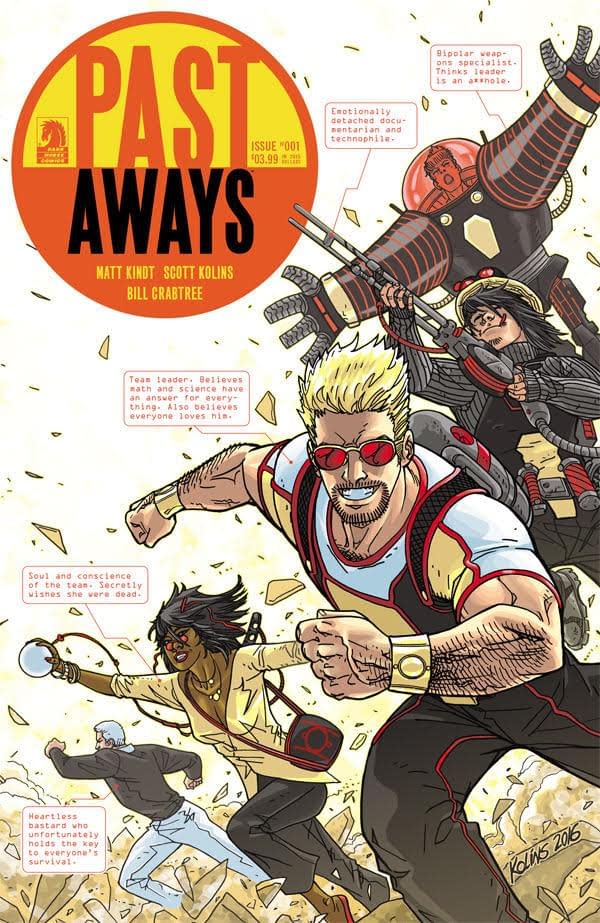

BW: I'm a sucker for time travel stories, so Past Aways appealed to me right away when I read the initial paragraphs about it in a document Matt sent with a bunch of his ideas for different series. The initial pitch also made me think a little of the original Challengers of the Unknown, which I love, and while we've moved away from some of those elements—as well as the original title, FourEver Men, in part because there are now five main characters—there's still some of that flavor.

Part of it is that it's a traditional ongoing series. Whereas something like MIND MGMT had its ending planned from the beginning and its exact length nailed down fairly early, Past Aways has an ending, but it is also designed to be able to accommodate all kinds of detours and the inclusion of whatever is interesting Matt or Scott at the moment. That's not new—Grant Morrison described exactly this when writing about Sandman in his original pitch for The Invisibles—but it's not something we do as much anymore outside of DC and Marvel and some of the big Image series like The Walking Dead or Saga.

I think what ongoing series are great at is developing an exciting but broad enough premise that you can kind of go anywhere, and explorers from the distant future trapped in our time is a great example. There are so many things they can encounter that have nothing to do with their immediate predicament but that still resonates with them. Great sci-fi comments on our own world, and we have the shortcut of literally taking people from the future and having them react to the present. Meanwhile, trying to get home forms a consistent backdrop. It sounds really calculated when I put it like that, but like a lot of great ideas, much of this fell into place as the series was developed.

And just seeing the world come together has been a pleasure. Matt asked Scott what kinds of stuff he likes to draw and has worked a lot of it in, and in the scripts many of the exotic technologies are left to Scott to make up, with a note saying, "I'll figure out a caption for whatever you draw." Scott has a wonderful visual imagination and has given the future technology an organic and consistent look.

BW: I think you have to have something to say, but you need to be able to express that through the projects you choose rather than trying to make your projects say what you want them to. The cliché of editors being failed writers isn't as common as some people make it sound, but it exists, and I'm sometimes thanked for not trying to write over people, but that often feels like being thanked for breathing, since it's just what comes naturally. I'm not resisting an urge; I honestly have no desire to write comics.

You have to be confident in your taste and push for the things that matter to you. I advocate for comics that I want to read and things that I think people I know want to read, and I love working with newer artists, that thrill of discovery. It's also important to be open to suggestions. Editors end up knowing a lot of artists, but writers and other artists know many more, and a lot of the best people you find are people that someone else recommends to you.

An ability to see what writers and artists are trying to do in their storytelling and to offer guidance on making sure it comes through is important, but I approach that less as making sure the rules are followed and more just going on my reaction when I read it. Did that scene make sense? Is something over- or underexplained? I think this scene was trying to make me feel this. Why did it do that or not do it? Most of my notes are presented in the form of questions, and anytime I suggest something specific, it's meant to prompt a writer or artist to reply with their own, better idea. But, and this is also a cliché, the goal is to not have to give notes. You pick the right project with the right people and you make sure everyone knows before you start what you're trying to accomplish, and ideally you as the editor don't have to do a lot more after that than keep to the schedule.

Beyond that, to make a career out of it, to last? I dunno if I'm qualified to answer that. I don't consider myself to have lasted yet. I'm still less than seven years into doing this for money, and turnover in comics being what it is, that is kind of long in a way. But it's not that many years. It's a weird business; there's not a lot of money in it. Comics are a low-margin product so you can't get away with not selling very many of them, and it hurts when something you believe in doesn't sell. It hurts as much today as it did when I first started. You have to be able to be disappointed, sometimes brutally, and pitch the next project with the same enthusiasm. You have to be good with a lot of different kinds of people: administrative workers, freelance artists, staff designers and artists, agents, bosses, movie and video game people; you end up working with everyone.

I think my greatest strength as an editor is that I fall in love with every project I do. I get assigned stuff sometimes that I don't have a natural affinity for, but it's an important or necessary book and either because of a particular skill I have or simply because my schedule is where it will fit, it goes to me, and I find my connection to it. I get as protective of it as all the others. Especially when you're at a stage where you mostly edit what you're assigned—and I'm lucky enough at this point that nearly all of my projects are either things I brought in or things I requested to be assigned—it's pretty important to be able to do that, to find what it is about a project that makes you love it. Sometimes it's the chance to work with a specific artist, or it's getting to try something with a design that you haven't before, or through it you get to learn about comics history, but there is always something. I'm very lucky to get to do something I love, but whenever you love something, the personal stakes are high, and it can be hard, so figuring out how to get through the times that love hurts, keeps you good at your job and allows you to keep doing it.

BW: Originally I wanted to avoid working in comics for fear it would harm my ability to be a fan of comics. It has permanently changed my relationship to the comics I read, even the ones I have nothing to do with, but in the end I feel like working in comics has enriched my relationship to the medium more than seeing how the sausage has made has complicated it.

My parents are both criminal defense attorneys, and my dad pushed me to go to law school for several years, but I never seriously considered that. I did do some freelance paralegal research, which I think gives me some small insight into the freelance lifestyle of the people I work with, and took the very earliest steps into studying for an investigation license, but didn't go very far. The cases I worked on as a researcher, including the largest offshore bank fraud case in American history, were fascinating, and I got very into them, working around the clock and doing extracurricular stuff like reading a biography of Charles Ponzi during the bank fraud case, which the government was describing as a Ponzi scheme. But for the most part that was just to make money—and it was pretty good money—not something I thought would be a real career.

The main thing I thought about doing before comics was film, which I went into a little bit before, but in part because living in LA didn't really work out for me (though it is much more livable today than it was then) and in part because I wasn't all that inspired by the people I met through film, I started looking at other stuff. The short time I spent doing film work in Portland was denial, I think. Because I happen to be from Portland, which is such a comics hub, I decided to give that another look. At that point, I'd only been out of college about a year, and it actually didn't take that long to start finding the gigs like Stumptown and Top Shelf and my teaching. I started at Dark Horse when I was 24.

Compared to film, comics moves a lot faster and is able to take more risks, since the budgets aren't so ridiculously out of scale. The money thing does go both ways, of course; almost no one in comics is paid enough, but that's because there really isn't that much money to go around. I am all for comics being more respected and taught in schools and reviewed in literary magazines and all that, but I still like how disreputable we are and how much that means we can get away with since there are fewer eyes on us. Books like Grindhouse are born out of that, though ironically that series has become one of my bigger hits. The freedom is great, and I like that it's a small enough community that you can get to know a large portion of the American field, even if only a little. Comics very much becomes a lifestyle.

HMS: Thank you so much, Brendan, for doing this monumental interview with such a retrospective about your career included, as well as looking at the beginning of a new era for you as full Editor at Dark Horse and starting a new project with Matt Kindt. We wish you all the best and thanks for all the great comics you've helped bring to our shops and shelves.

MIND MGMT #35 will arrive in shops on July 22nd.

The "New MGMT" final issue, #36 will arrive in August.

Past Aways #4 arrives today, June 24th in shops.