Posted in: Comics, Vintage Paper | Tagged: daily graphic, robert bonner, the issue, thomas wust

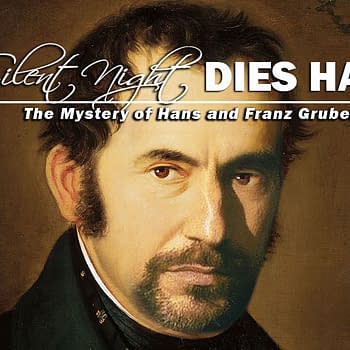

THE ISSUE: The Daily Graphic and the Right to One's Face

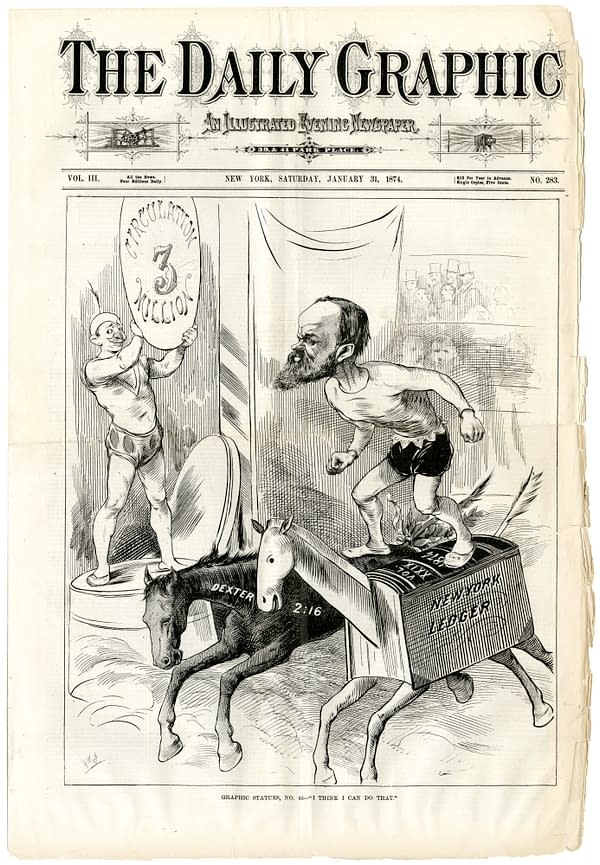

This issue of The Daily Graphic No. 283 January 31, 1874 is doubly interesting to me because the cover page is a cartoon about a story paper — The New York Ledger. The Issue is a regular column about vintage comics and other vintage periodicals from throughout world history. The idea behind The Issue is simple: for each post, I'll choose something from my collection and talk about what's going on in it, and discuss the publishers and creators behind it. And essentially I'm just going to end up stepping through comics history one issue at a time. There is just one rule in The Issue: No recent stuff. Everything will be from before 1940, and most of it will be from before 1920.

When I first got into dime novel & story paper collecting, I thought there was a current newspaper called The New York Ledger. There isn't, but I thought so because I'm a Law & Order fan. The New York Ledger is the franchise's go-to fake newspaper name. The real New York Ledger is actually one of the most successful story papers of the 19th century. Journeyman printer Robert Bonner purchased The New York Merchant's Ledger in 1851 and transformed it into The New York Ledger in 1855. Bonner was able to make the paper a success by paying some of the best writers of the era very well. These included Fanny Fern, E.D.E.N. Southworth, Sylvanus Cobb, Jr, and an interesting one from our perspective here — former Governor of Massachusetts, President of Harvard, and U.S. Secretary of State Edward Everett. Everett wrote an American history column for the Ledger and is an ancestor of foundational Golden Age comics creator Bill Everett.

Daily Graphic before Graphic Novel

The Daily Graphic might be the most under-studied comics-related periodical in American history. The illustrated newspaper was launched by pioneering Canadian printers, engravers, and inventors George-Édouard Desbarats and William Leggo, who developed "Leggotype", a photographic method of reproducing line drawings, which was later refined to be used with photographs. On October 30, 1869, the pair launched the Canadian Illustrated News with what is regarded as the first-ever photo printed in a newspaper. The pair then took their pioneering techniques to New York City, launching The Daily Graphic in 1873 as the first true illustrated daily in the United States. The paper was a financial failure due to lavish promotional spending, but was innovative in a number of ways, including in its publication of weather maps. It must also be noted that along with the UK's The Graphic, The Daily Graphic represents an early usage of the term "graphic" in association with a comic art-related publication — long before the phrase "graphic novel" entered common usage.

The cartoonist for the cover page of this particular issue is Daily Graphic regular Thomas Wust. The Daily Graphic usually has a blurb about the cover on the next page, and this one says:

The cartoon on our first page represents the proprietor of Dexter and of the Ledger determined to achieve a circulation of 3,000,000 for his well-known paper. The horses are studied, one from life, the other from a model belonging to the youngest son of the artist. The fidelity of the likeness of the equestrian editor will be promptly recognized. The picture is full of spirit and other things, and is a fair illustration of the career of the successful man who, has curiously yoked together fast horses and steady-going newspapers.

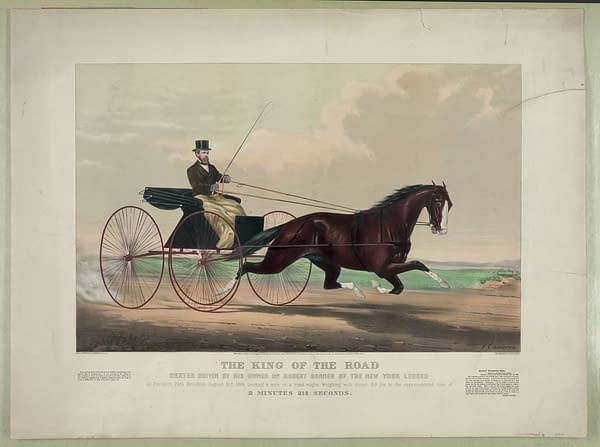

The Legend of Dexter

Robert Bonner parlayed his New York Ledger earnings into racehorses. By the time his stable was sold off by his family at the turn of the century, it was considered the finest horse stable in New York, with a reputation for producing some of the best horses. As for Dexter, he was one of the most famous trotters in the country during his run. The Dexter Cup, named in his honor, is a major annual horse-racing event to this day. The town of Dexter, Kansas was also named after Robert Bonner's legendary trotter.

When Dexter passed in 1888, The New York Times ran an obituary which appears to explain the 2:16 on his side in Wust's cartoon here. Dexter set a world record for a one-mile race first at 2:19 and then bettered that with 2:17 1/4, and himself was only beaten a handful of times during his career — once by a rival who finished at 2:16. So, it seems that while Bonner was chasing circulation numbers with the Ledger, he had also been chasing 2:16 with Dexter.

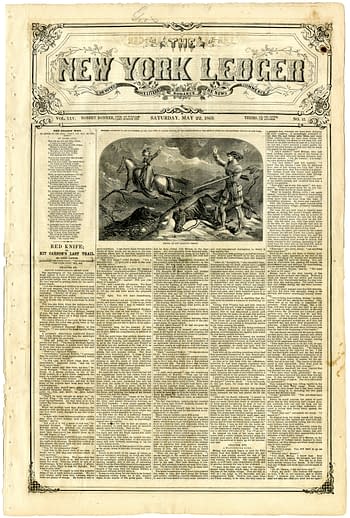

- New York Ledger Volume 25 Number 13 1869-05-22 Kit Carson, published by Robert Bonner.

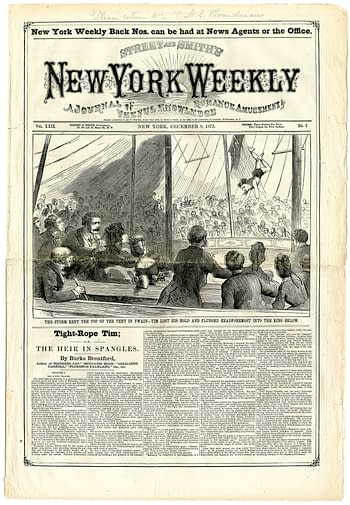

- New York Weekly Volume 24 Number 5 1873-12-05 Tight Rope Tim, published by Street & Smith.

Circulation 3 Million?

But in regards to "Circulation 3 Million"… that would seem to be either part of the joke, or a misunderstanding on the part of the artist. Taking a look at the best data available, which is Rowell's American Newspaper Directory for 1874, we see that the paper likely to be Bonner's most successful story paper rival at this time — Street & Smith's New York Weekly — is listed with a circulation of 200,000. The New York Ledger itself did not accept advertising, and so there is no data listed for the paper in either Rowell's or Ayer's. Even a typical bellwether like Harper's Weekly is listed at 105,000 in '74.

An 1889 Garden City, Kansas newspaper story titled Millions Made in Story Papers may give us a clue as to what Wust may have meant with that 3 million number in his cartoon. It says:

The New York Ledger started in 1854 and in two years had 200,000 circulation. Its highest circulation has been 350,000. Robert Bonner made three million dollars out of it. Two years ago he turned it over to his three sons, and retired from business.

While we must take all the numbers with a grain of salt, it seems possible that Bonner's push towards $3 Million was well-known, and Wust chose to use that outrageous-sounding number as his cartoon hook. This article Millions Made in Story Papers is interesting, and I'll break it out into a separate post shortly. In the meantime, I'll leave you with this cartoon-adjacent article also from this issue of The Daily Graphic, which covers right to likeness and caricature controversies of the time:

The Right to One's Face

The Times of this city has recently devoted a good deal of space to the discussion of the right of illustrated papers to publish portraits of men and women whose faces are of interest to the public. Now the right to publish such portraits is not a matter of opinion, but of law. When a person goes to a photographer's and has his portrait taken, he can, if he chooses, copyright it. If he does so it is his private property and can-not be used by any illustrated journal without his consent. If he neglects to do so, the photo-graph is simply a publication without a copy-and he has no such property in it as to authorize him to prevent its use by any proprietor of an illustrated publication. It is not to be expected that the Times should be familiar with American law, and its assumption that every man has a natural and inalienable right to the exclusive use of an uncopyrighted photograph is therefore excusable. But between the right to use such photographs and the uniform exercise of that right THE DAILY GRAPHIC has always made a distinction. When a person requests as a favor that his likeness shall not be published such favor is granted, except where the request is obviously unreasonable. That women who promenade the street and frequent balls and public entertainments for the express purpose of displaying themselves should affect to object to the publication of their portraits usually an affectation which no editor is bound to respect. And when the objection to such publication is couched in tho form of a peremptory demand that the portrait shall not be published, the editor is certainly at full liberty to pursue such a course in the matter as may seem fit to him.

THE DAILY GRAPHIC has uniformly listened to all requests when made. It is only recently that it refrained from publishing a sketch of a wedding which was celebrated with all the publicity which thousands of invitations, the presence of brass-bands, and other features separating it wholly from an ordinary private party could give. At the request of those most nearly interested in the affair, the sketch was withheld from publication. Had this request, however, come in the form of a peremptory demand, there certainly would have been abundant justification for a refusal to accede to it.

The theory of the Times, that while "all that a man does for the public " is a proper subject of remark, no journal has any excuse "for saying or doing anything in regard to his person," is obviously untrue, It was generally thought that the person and dress of Mr. Greeley were occasionally alluded to in the Times during the Presidential campaign; and that journal's weekly praise of Mr, Nast's caricatures of Mr. Greeley, of the editor of the Tribune, and all the prominent advocates of the Democratic candidates, can hardly have been forgotten. How does it happen that it was right for the Times and Mr. Nast to caricature and ridicule the personal appearance of political opponents, and wrong for THE DAILY GRAPHIC to publish accurate portraits of men like the late Mr. Bristed? The whole theory upon which the Times proceeds is not only without any just foundation, but, if true, would compel it to retract and apologize for a large proportion of the leading articles which it published during the Summer of 1872.