Posted in: Comics | Tagged: chicago, dc

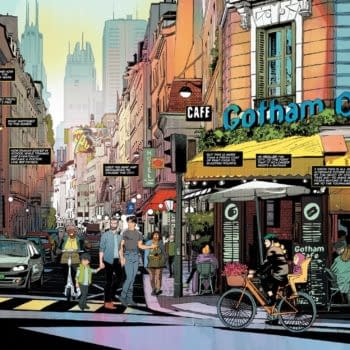

Gotham City, Illinois: Pinning Batman's Mecca on the Map

Stephen Sonneveld writes for Bleeding Cool

In 1932, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster sat on a Ohio hillside, looked up in the sky and imagined a man flying through it. The young men developed a comic strip about their bounding, bulletproof hero, and set his adventures in the Cleveland they knew – and where they hoped one of its newspapers would buy the strip. Comic strips were the prestige medium for cartoonists of that time, but six-years of rejection letters finally convinced the duo to take their creation to the fledgling comic book industry. If those editors liked what they saw, at least Superman would see print in some form.

Did he ever.

Superman leaped over the tall buildings of an unnamed major metropolitan city until Action Comics #16 in September 1939, when his home turf would become Metropolis, evermore. Superman #2 of that same year went one step further, when Clark Kent sent a telegram to his editor in "Metropolis, N.Y."

Of course it was New York. It had to be that state, because it had to be that city.

The first generation of comic book readers identified with Superman because he was an all American man who had immigrated to Earth and eventually landed in Metropolis, just as their families had landed in New York. Superman's story was a melting pot of Moses, Osiris, Hercules and other old world myths refashioned in the bright, burning hope of a new land. Theirs was a street-level Superman who took the fight to slum lords and bent politicians; a character who used his immense power unabashedly for the good of all – the promise of America in primary colors.

Though German director Fritz Lang and his screenwriter wife Thea von Harbou had already been developing the idea for their Metropolis for a number of years, Lang cited a vacation to New York, and how the awe of standing under its skyscrapers influenced the epic cityscape on display in his 1927 film. That landmark of cinema features a dystopic vision of man fighting for his humanity in the age of automation, but the Metropolis of comics remains one of enduring light, and Superman – fighting for humanity against all threats – its sun.

When the United Nations Headquarters were completed in 1952, New York ostensibly became the capital of the world, and no New Yorker would ever have you believe otherwise. Displayed there is a sculpture of a Colt pistol with its barrel tied in a knot – a Superman inspired symbol if ever there was one.

During Richard Donner's beloved epic Superman (1978), the Man of Steel takes feisty reporter Lois Lane for a romantic flight over Metropolis, wherein they pass a number of New York city area landmarks, including the Statue of Liberty where all those immigrants first arrived. There was no need for the film's producers to construct a newspaper building with a giant globe, because one already existed (the New York Daily News). Lex Luthor's brilliantly designed lair was set in the Big Apple's famous subways, making Luthor lord of the underworld in every sense. No viewer batted an eye at these references because there was no disconnect.

Metropolis is New York.

Yet, the DC Atlas places Metropolis somewhere near NYC, as opposed to just overwriting it and embracing the mythology years of super stories had been stoking. Some poor town on the map was going to get substituted, yet DC wasn't brave enough to make it the appropriate one. The home of Superman's crime-fighting ally Batman doesn't fare much better on the DC Atlas, which places Gotham City in Jersey, within view but a world apart from Metropolis on that crowded Northeastern seaboard.

Notwithstanding, the prevailing theory among comic book writers is that Batman's famous home is also a stand in for New York. Frank Miller offered that Metropolis was New York by day while Gotham City was New York at night. Denny O'Neil specified, "My standard definition of Gotham City is, its New York below 14th Street after eleven o'clock at night. Recognizably New York, but with an emphasis on the darker aspects of the city." In Tales of the Dark Knight: Batman's First Fifty Years: 1939-1989, author Mark Cotta Vaz asserted, "Although it was meant to be a fictional place, it was – and is – clearly modeled after New York."

This seems contrary to the intent of Bill Finger, the writer who shaped with Batman creator Bob Kane the character's early adventures and memorable rogues gallery, who claimed, "We didn't call it New York because we didn't want anybody to identify with it." Stumped for a good name, Finger thumbed through the New York City phone book and happened upon the G-word. Though Bruce Wayne had begun prowling alleyways a year prior, Batman #4 in Winter 1940 marked the first time Gotham City saw print in his books.

It was writer Washington Irving, in 1807, who created "Gotham" as a satirical pseudonym for New York, in reference to the town in Nottinghamshire, England, which was famous for being inhabited by fools. Folklore has it that the 11th century villagers didn't want the expense of a planned Royal Highway, so when King John's knights came to survey the land, the people acted insane, a condition that was thought to be contagious at the time. Before idiots, it was known for its goats, from which the name in Old English derives: gat (goat) + ham (home) = "homestead where goats are kept".

Just as the mythos of Superman outgrew his Cleveland roots, so, too, has the Dark Knight evolved from that tangential connection to New York. Batman is too fully realized in the public imagination to reside in only half a city for half the day. This rich character exists in his own space, one geographically apart from the Man of Steel, and one more organically representative of his essence.

The argument that Superman (NY by day) and Batman (NY by night) are two sides of the same coin is only true on the superficial level. Ideologically, at their moral core, the characters are essentially the same man. They're on the same side of the coin – it is Luthor and Joker who represent their opposite numbers. Batman and Superman are wholes, not halves, and it is the details of their differences that makes each unique and intriguing. Superman is the champion of a shimmering city, forced to confront it's seedy underbelly, while Batman must protect a city with a notorious reputation, without forgetting the beauty it offers.

New York is a Gershwin tune, but Chicago is a Sandburg poem; lyricisms reflected in Superman and Batman.

Metropolis is New York. Gotham City is Chicago. Time will tell if the editors of any future DC Atlas will be bold enough to put the original comic hero's Metropolis atop the media capital, and the Gotham of comics' second hero atop the Second City, where each belongs.

Chicago has always been a city of duality, the perfect home for a Dark Knight. The World's Columbian Exposition of 1893 created a "White City" of neoclassical elegance that is said to have influenced L. Frank Baum's visions of Oz. Frederick Douglass, born a slave, was invited to be an international delegate. Modern gods Tesla and Edison traded lightning bolts in competing electrical exhibits. From the whimsy of the first Ferris Wheel to the forward thinking Parliament of the World's Religions, the six-month fair truly was a celebration – yet would close not with festivities, but with funeral and memorial services for the assassinated mayor, shot in his home by a deranged man.

Whether the result of pistols or meat-packing, blood always seemed to run in Chicago streets. Yet it is from those same stockyards where an early Batman prototype emerges. In 1906, journalist Upton Sinclair worked undercover, then exposed the graft, exploitation, unsafe conditions and human misery of life in a company town with his seminal work The Jungle. Though public outcry didn't have Sinclair's desired effect of focusing on the worker, it did lead to immediate food safety laws and eventually to the creation of the Food and Drug Administration. Sinclair didn't have a cape, but he was no less a crusader.

The same could be said for Jane Addams, who turned a dilapidated mansion at 800 South Halsted into Hull House, a settlement house that set about to give social, cultural and educational opportunities to the patchwork of poverty-stricken immigrant communities, and became a political force that helped create a number of legal reforms, such as the creation of America's first juvenile court, worker's rights, unemployment compensation, child labor laws and women's suffrage. Her commitment to pacifism in the face of the first World War and beyond, made her the first American woman to be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

Though Addams' efforts earned her international acclaim, most Americans visiting abroad throughout the 20th century discovered that many people the world over envisioned the United States as either the Old West, or urban hellholes besotted with gangsters – no doubt why every American carries a gun. Both of those archetypes have root in the Windy City, and provide the perfect soil from which a character like the Caped Crusader could grow.

Western fiction, lore, cinema and later TV contributed to the cowboy stereotype, though by the time of Batman's arrival in 1939, all the men and women who lived those days had passed into legend, including Illinois-born Wyatt Earp. The lawman's exploits would be dramatized for years to come, though at the time of his death, he couldn't even convince the cowboy stars of silent film that his was a tale worth telling.

Instead, when Batman began, it was the gangster who was at the forefront of the collective memory, immortalized in fedora and pinstripes by the man who ran Chicago, Al Capone. When Prohibition ended in 1933, the tumult of those years, and the legend of Scarface Al's murderous rise and tragic fall gave film noir and the pulps a bloody relevance.

Fictional Bruce Wayne was born from blood in the streets, having watched his mother and father gunned down before him. It's no stretch to imagine that boy growing into the type of lawman – especially, in Batman's early, gun-wielding adventures – that would put a bullet in the back of John Dillinger's head outside a crowded theater. As their storytelling matured, Batman's creators reasoned that a boy who witnessed his parents die in cold blood would have an urge to protect life, not take it. The character's metier ever since has been to avenge, not out for revenge.

That moral stance only bolstered another of the Dark Knight's traits – investigating; he made his first appearance in Detective Comics for a reason. Batman's obsession to rid the world of crime remained in tact, but his methods became those of cool logic, reason and deduction. He had evolved from the type of emotional response that would leave public enemy number one dead on the sidewalk, just like crime-fighters in Chicago had learned to do the same.

It was Capone's city, and everyone else was just living in it. Scarface convinced himself he was Robin Hood, giving the people what they wanted, damn the unjust laws. Conservatives, such as industrialist John D. Rockefeller, were able to get their temperance opinions made into law when the Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution went into effect in 1920. By 1933, Rockefeller finally realized how legislating morality brought about fearful consequences, writing, "Instead, drinking has generally increased; the speakeasy has replaced the saloon; a vast army of lawbreakers has appeared; many of our best citizens have openly ignored Prohibition; respect for the law has been greatly lessened; and crime has increased to a level never seen before."

Needless to say, Capone was making a killing. City officials, judges and cops were all on his payroll, putting him on par with the organizational support of fictional Gotham crime boss Carmine Falcone. However, the open violence of events such as the St. Valentine's Day Massacre put Scarface in league with the sociopathic Joker. Just as Commissioner Gordon and Batman would face the corruption and vice in their city, fearlessly into the lion's den walked Elliot Ness and his small band of trusted lieutenants who valued justice more than payoffs, their city more than their own safety.

As with any great detective story, the Untouchables didn't defeat dear Alphonse because they outgunned him, they beat Capone because they outsmarted him – twice, in fact. First, since the well-greased wheels of injustice stymied the crew from being able to make a murder, racketeering, prostitution or smuggling charge stick to the boss, they went after him for tax evasion, resulting in an indictment. Upon discovering the mob was paying off and intimidating the jurors for Capone's upcoming trial, the feds convinced the judge – on the day of the trial – to bring in the jury from the courtroom next door. It was a swerve worthy of David Mamet's imagination, screenwriter of the 1987 feature The Untouchables, but it was no invention.

Ness and the Untouchables are a high water mark in the lineage of the Chicago crime-fighting detective, but the greatest of them all not only shares common ground with Batman, but also with that cowboy who once roamed Gotham City's Old West – Jonah Hex.

Grant Morrison's 2010 Return of Bruce Wayne story hammered home to distraction the canon that Gotham was an east coast city. No issue was more jarring than #4, which featured the gunslinger Jonah Hex on the hunt in a Wild West Gotham.

The Clint Eastwood version of the Old West Hex inhabits bears no resemblance to post-Civil War, or even antebellum New York. The urban slums of the city's Victorian age existence is documented in grimy detail both in the nonfiction book and fictional film of Gangs of New York. Kingpin fences such as "Marm" Mandelbaum were the big time operators in the city. The image of cattle rustlers and bandits on horseback is a far cry from the upscale dinner parties Mandelbaum hosted for Tammany Hall officials and her underworld friends.

In the comic pages, Hex began bounty hunting after the Civil War ended in 1865. Ever dichotomous, the Chicago of this era was trapped between two worlds. The city was incorporated in 1833, and it's access to waterways, as well as being a major railway hub, contributed to population and industrial growth. The city gained a cache of celebrity in the 50's for being the home of the "Little Giant" Stephen Douglas, who was making national headlines debating political rival and Illinois neighbor Abraham Lincoln.

Considering that the Great Chicago Fire of 1871 was believably blamed on a cow – thanks to a reporter wanting colorful copy – or that another explanation blamed a man who snuck into the barn to steal said cow's milk, it isn't difficult to imagine a gunslinger walking down a dirt street of wooden building after wooden building, but it is still not the Eastwood West. After the Fire decimated much of the wooden city, Chicago marched toward progress, erecting the world's first skyscraper in 1885. Out of the ashes, the modern city and steel-framed structures rose, leaving rurality in its past. Batman would certainly be at home in such a place, but not a cowboy.

Where Chicago has a link to points west is in Detective William Pinkerton. Not only is Pinkerton a viable example of a Jonah Hex Western hero operating out of the Windy City, but he is also the best example of a living Batman, as well.

After Allan Pinkerton's death in 1884, his youngest son Robert took over the New York office, ensconced in paperwork, while William took the reigns of the Detective Agency's Chicago headquarters. Like his city, like the very age he lived in, William was a man of duality.

First, it was not uncommon for Pinkerton to be in his Chicago office one day, then hopping a train to Denver the next, so as to saddle up in pursuit of whatever bank robber, horse thief or killer was terrorizing the dusty plains. Utterly fearless, he earned his reputation bringing to justice the likes of Kid Curry, Texas Jack, and Butch and Sundance. Wounded in a shootout with the Farringtons, Pinkerton nevertheless got close enough to pistol whip the gang into surrender. Jonah Hex would be proud to call a man like that friend.

The Pinkerton Detective Agency filled a need in a country with no FBI and a world with no Interpol. From the New York office, Robert's communications with foreign police forces looking for the Agency's aid, amassed an international database of criminal offenders. The Canadian government reportedly relied solely on the Pinkertons for all investigation and security needs. Not unlike Morrison's Batman, Inc., a less altruistic private agency of such information and influence could bend the world to its will, except that – as with Ness a generation later – the Pinkertons prided themselves on absolute incorruptibility.

Scotsman Allan Pinkerton founded the Agency in Chicago in 1850. President Lincoln tasked him to be wartime spymaster, and Allan had no issue sending William on missions into Confederate territory – that is, when William wasn't involved in the usual business of war, such as fighting in the Battle of Antietam. For their logo, the Pinkertons chose an unblinking human eye, accompanied by the motto, "The Eye That Never Sleeps", a psychological warning to the suspicious and cowardly criminal lot… as much as a man dressing like a night terror. That logo, their Bat Signal, became so ingrained in the public consciousness that the term "private eye" remains to this day.

Just as Gotham city scumbags tremble in panic at the idea of Batman lurking in the shadows, Gilded Age safecrackers, fences and outlaws all came to fear the dogged pursuit of the man they called the Eye. Criminal Eddie Guerin said of his bane, "When Bill Pinkerton went after a man he didn't let up until he got him. If it cost him a million dollars, he didn't mind." In addition to the Eye, burly William was also christened the Big Man. When the Agency founded the Protective Association of American Bankers as a division offering specialized protection for banks, reputation alone kept criminals away. In the words of burglar Josiah Flynt, "The guns would leave the Big Man's territory alone, if they can. If there was two banks standin' there close together… the gun's 'ud tackle the other one first. The Big Man protects the Bankers' Association banks." Caped Crusader or the Eye, Dark Knight or Big Man, fear invoked legend.

It has been said among comic book creators that Superman is the disguise of Clark Kent, but Bruce Wayne is the disguise of Batman. Such a sentiment would have resonated with William Pinkerton. His obsession sustained him; the cause of nabbing crooks and bringing them to law ever-present in his thoughts. Yet, the final duality in Pinkerton's nature is that he would become most at home among the criminals who occupied his mind. That strange kinship prompted Pinkerton to hire many of the ex-cons he put away. Unusual for his time, Pinkerton wasn't afraid to show admiration for particularly clever or daring crimes, and when Adam Worth, the gentleman thief Pinkerton had been pursuing for decades, finally made the Big Man his confessor, a lasting friendship endured. In comic books, fictional Batman met fictional Sherlock Holmes, but in a Chicago office, our real life Batman befriended the criminal who was the basis for Moriarty.

The dichotomy of Chicago lives on. Her spirit is Batman's spirit. As Christopher Nolan's elegant films demonstrated, just as Superman had for that hero, years before, there was no disconnect in audiences seeing the black cape take wing over Chicago landmarks. Fictional Gotham City on a real world map would be pinned on the southwest shore of Lake Michigan. It is here, this strange current of spirits, that can produce the murderous evil of would-be geniuses Leopold and Loeb, but also the humanism of genius Clarence Darrow to defend them. The incorruptible cops of Gotham's four-color fiction seem to have risen from the same clay as Chicago's crusaders, detectives and defenders.

Consider 2008: Chicago is the murder capital of the United States, yet Grant Park was flooded with people in celebration of one of their own winning a historic election. To embrace hope in defiance of the blood in the streets – this is Gotham City, this is Chicago, this is Batman.