Posted in: Comics, Recent Updates | Tagged: Buffy Season 10, Comics, dark horse comics, entertainment, hawkeye, image comics, low, Marvel Comics, new avengers, Serenity: Leaves on the Wind, Sir Edward Grey, The Manhattan Projects, The Mysteries of Unland, Witchfinder

Thor's Comic Review Column – New Avengers, The Manhattan Projects, Serenity, Buffy, Sir Edward Grey, Low, Hawkeye

This week's comics include:

New Avengers #21

The Manhattan Projects #22

Serenity: Leaves on The Wind #6

Buffy Season 10 #5

Sir Edward Grey, Witchfinder, The Mysteries of Unland #1 & 2

Low #1

Hawkeye #19

New Avengers #21 (Marvel, $3.99)

By Cat Taylor

For those of you who have been keeping up with Jonathan Hickman's New Avengers, this issue is the climax of everything. It's a payoff that's somewhat expected yet manages to be unpredictable. For those of you who haven't been keeping up, the first thing you need to understand is that the New Avengers comic book isn't about a current team of Avengers at all. It's about that group of superhero geniuses and world leaders informally known as the Illuminati. Their purpose is to covertly work to manipulate events for the good of the world using any means necessary. In the Brian Michael Bendis Illuminati mini-series from a few years ago, he explored how they secretly worked behind the scenes during some of Marvel's most significant events. In most cases, the results caused more harm than good. In every situation, the morality of their methods was questionable, especially by standard super-hero principles.

In the currently ongoing New Avengers series, Hickman has taken Bendis's exploration to a new level. For the past several issues, the Illuminati has been preparing to use a bomb that can destroy an entire planet because our Earth (616) is on a collision course with a parallel/alternate-universe Earth that will destroy both unless something can obliterate one of the worlds before they collide in an event known as an "incursion". It's probably no coincidence that Hickman made sure that Mr. Fantastic was one of the architects of a world-destroying bomb given that he also used a similar device (the Ultimate Nullifier) to prevent Galactus from destroying Earth for his own survival way back in Fantastic Four volume 1, number 50. Of course, everything in comic book storytelling 101 should lead a reader to believe that despite all evidence to the contrary, somehow these brilliant and noble heroes will find a way to avoid destroying an entire world and still manage to save their own. However, comic book stories are more sophisticated now and the Watcher showing up with a deus ex machina won't cut it in today's Marvel universe. I won't give away the final solution here, but I will say that three of the heroes in the Illuminati directly commit some level of major villain-level atrocity during the course of this issue. So, one way or another, Hickman isn't letting anyone off easy.

Most people I know don't really want to see more super-heroes dragged down to 1990s anti-hero level. Yet, this isn't a matter of turning everyone into a dark and brooding version of Wolverine with a giant laser gun. Instead, Hickman has created moral dilemmas that are more complex than comic book heroes typically face and puts his characters in a no-win situation. This is a story where Hickman uses his strength of verbal storytelling and exploration of the super-hero philosophy/psychology and he does it very well. It's somewhat ironic that the artists for this issue, Valerio Schiti (You just know other kids made fun of his name in grade school.) and Salvador Larroca, use a style that is more akin to the Cartoon Network Marvel animation than a more realistic style that would typically be expected for this kind of story. Fortunately, the unusual collaboration isn't distracting or comical. In fact, I probably wouldn't have thought anything about it if I wasn't writing a review of the issue.

There are many obvious moments throughout this story that get to the heart of the matter and a couple of them should really make any reader question what differs some of these "heroes" from villains like Dr. Doom and Magneto, who also believe their actions are for the better of their people. Right in the middle of the book, Black Bolt's brother, Maximus explains the situation better than I ever could when he says, "You're used to dealing with heroes…but what you don't have much experience with is kings…Their very idea of morality is different than what you are used to." By going there, Hickman has added a level of moral ambiguity to the Marvel universe where we should no longer simply define characters as heroes or villains. There is now another distinction, and it's one that exists in reality when world leaders and the military go to war because they believe the countless deaths that will surely result are worth the cost for their countries. It's always a controversial decision that creates endless debate. Now, that part of reality is also in our fantasy world. Pleasant dreams, kids!

Cat Taylor has been reading comics since the 1970s. Some of his favorite writers are Alan Moore, Neil Gaimen, Peter Bagge, and Kurt Busiek. Prior to writing about comics, Taylor performed in punk rock bands and on the outlaw professional wrestling circuit. During that time he also wrote for music and pro wrestling fanzines. In addition to writing about comics, Taylor tries to be funny by writing fast food fish sandwich reviews for Brophisticate.com. He has the dubious distinction of not having a Twitter account but you can e-mail him at cizattaylor@hotmail.com.

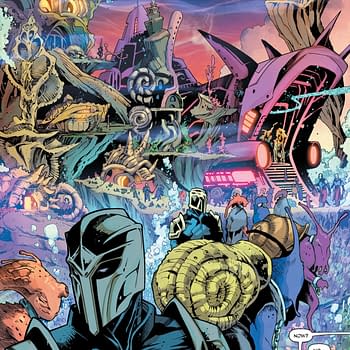

The Manhattan Projects #22 (Image, $3.50)

By Joe Colewood

Ever since the Enlightenment (and even that name is a giveaway, isn't it?), western society has been wildly conflicted about science. There are a whole host of philosophies, positive and negative, that have been attached or ascribed to the concept of "science" over the years, despite the fact that it supposedly exists completely apart from humanity's biases and desires. Many of these are fascinatingly contradictory; the culture of science has been demonized by both the political right and the left, seen as both a threat to the status quo and as a tool of oppressive authority. And just as it's often portrayed as the tool of humanity's inevitable downfall, it's occasionally championed in its own right as humanity's only hope.

I won't lie, as a SF-obsessed kid whose father was an engineer with a science degree, I've always leaned more towards that last one. I've found it dismaying to see how our culture has swung away from scientific principles in recent years—not just in the overt embrace of things like creationism and new age mysticism, but a more subtle rejection of rigorous, logical thought. It's the kind of thing that leads to people denying the existence of global warming, or believing that vaccines cause autism, or even the general tendency for people to cherry-pick evidence when it supports their beliefs while refusing to try to get a grip on the larger body of evidence.

Interestingly, there's been a pushback in recent years, a championing of science that's seen Neil Degrasse Tyson becoming a minor celebrity, a website called I Fucking Love Science becoming wildly popular, and the trailers to the upcoming Christopher Nolan blockbuster Interstellar expressly appealing to the philosophical thrill of space exploration. There are problems with stuff like this—it can be argued that a lot of modern pop-culture science "fandom" is ironically pretty shoddy in its application of logic and the scientific method, and that trying to treat scientific discovery with the same kind of mindless enthusiasm that you would apply to the Marvel blockbuster movies isn't likely to be good for anyone's dignity. Still, it's hard to fault the basic idea of reverence for science and for the men who have furthered our understanding of it.

So, with The Manhattan Projects, Jonathan Hickman and Nick Pitarra take that reverence, crumple it up, and urinate all over it.

Make no mistake, The Manhattan Projects is pure punk rock comics. Just as punk reacted to the peace 'n' love mentality and artistic seriousness of 60s music with sneering irreverence, TMP is a comic aimed at dismantling the cult of science and spitting in the faces of pretty much all the great men behind the achievements of the 20th century. Robert Oppenheimer (or rather, his evil twin Joseph) is a cannibalistic serial killer. Albert Einstein (or rather, his parallel-reality counterpart) is a thuggish sociopath. Enrico Fermi is a murderous space alien. Werner Von Braun is…well, he's still a Nazi. Even the warm and witty Richard Feynman is portrayed as a cowardly narcissist. And those are the "heroes" of this book.

Banding together to advance humanity's understanding of science well beyond their original mission of building an atomic bomb, the figures behind the Manhattan Projects have become the de facto rulers of the world out of simple necessity—they want to keep up their experiments unhindered by political entanglements, and to that end they've been secretly working alongside the Russians for years. This banding together for a common cause could be seen as noble in other hands' than Hickman's, but here of course it's purely about self-interest and control, and seems doomed to fail besides.

In past issues we saw the Projects clashing with the military-industrial complex, despite Oppenheimer's installation of a drug-addicted JFK as their puppet (did I mention this comic was irreverent?) In this issue we learn that the Russian government, newly led by Khrushchev, has been infected by a Thing-like alien colony and are set to re-ignite the cold war…and put the Manhattan Projects out of business.

Like I said above, I'm a guy who admires science and scientists, and that's exactly why The Manhattan Projects is such a useful book. It's good to have heroes, but it's also important, once in a while, to remind yourself not to put them on too high a pedestal. This is particularly important when you start thinking you're too smart to blindly worship anyone or anything—which is exactly the trap that "science fandom" may be falling afoul of.

Science is impassive, and exists apart from petty humanity. But our relationship with science is like anything else we humans struggle with, and it's good to be reminded of that once in a while…even in as snotty a way as this comic. Kill your idols. Think for yourself. Isn't that a rule we can extrapolate from science, too?

Joe Colewood is a great man, a man of vision. No one understands him. He had good reasons for doing the things he did. Consider the 20 years of peace in Lichtenstein, not to mention the electric toothbrush, and ask whether it was all worth it. The whereabouts of the bus full of nuns was never ascertained, anyway. You'll see. History will vindicate him.

And I Beheld, A Dark Horse – A Report from the Whedonverse, with a Slight Detour through Mignola Country

By Adam X. Smith

Whilst our mandate has always been pretty lax to accommodate everyone's schedule and purchasing requirements, one of the bits of feedback we've had during the teething process of moving into the Bleeding Cool neighbourhood is to try to keep it to one book per review per writer per week, presumably to keep things tidy and easy to follow – a reasonable request. However, due to the rigours of trying to get the comics I want on time to meet deadlines, plus the fact that I'm a stubborn dick who likes to write about what interests me right now, damn it all! – fuck it, here's a column about what I'm reading over at Dark Horse Comics. Notably absent: Brain Boy. Not sure what's going on there.

Anyway, here we go – it's the re-view, the re-view, whut-whut, the re-view.

Serenity: Leaves on The Wind is not the first comic Dark Horse has published in the Firefly wheelhouse, but it is the first one to be set in the direct aftermath of the film, with many key characters dead and the beginnings of a shake-up in the status quo as an Occupy-style resurgence of the Browncoat movement led by a group of young idealists, and Zoe being sent to a penal colony shortly after giving birth. The Serenity crew have seen better days, and it'll take some unlikely alliances for them to get Zoe back.

With the sixth and final issue, we get a nice wrap up of the main story, with an ending that raises just as many new questions as it seemed to answer, with gorgeous artwork throughout by Buffy Seasons 8 and 9 alum Georges Jeanty and Zach Whedon doing a serviceable job on a script that bashes along at a decent clip without really stopping to check if it makes a ton of sense. Sure, it's one of those scripts that would probably raise some questions if you stopped and looked at it a little longer, but fridge logic aside it's a decent imitation of the elder Whedon. Cameos from old favourites happen, in-jokes are made. It's not the crazy tone-shift that Buffy Season 8 was when it landed, and it's not a bunch of new episodes (more's the pity), but it certainly stands as evidence that the signal isn't stopping any time soon.

Speaking of Buffy…

I noted not so long ago that Christos Gage, whom I'd previously had limited exposure to, was the best thing about the finale issue of Superior Spider-Man, and his work so far on Buffy Season 10 with Angel & Faith penciller Rebekah Isaacs is some of the most animated work I've seen on a Buffy title. The timing helps, I suppose – the early arcs of these "seasons" tend to benefit from fresher eyes and a healthy amount of rebooting the status quo* – as in this case the Scooby Gang have to deal with the double-edged sword of magic being returned to the world after Buffy inadvertently destroyed it saving the earth from Twilight (not the one you're thinking of – although how cool would that be?) whilst still being highly unstable and in need of some beta-testing. In short, vampires are no longer mindless ravenous zombie-like beasts anymore, but they're also now able to transform into bats and wolves and fog ala Dracula, who makes a welcome return. Also Giles is back from the dead (don't ask) and in the form of a pre-pubescent boy with all that that entails (still don't ask).

Dropping in to the writer room for essentially a guest spot during the Dracula-Xander-Dawn love triangle arc (just… try not to think about it too much) is actor Nicholas Brendon, presumably to make sure that this is just as awkward an experience for us as it must be for him. I still don't see the benefit of Xander being in a relationship with Dawn, although they do find a few new tangles to that little conundrum whilst making what feels like the umpteenth retreading of Xander's role as butt-monkey to Dracula feel fresh again. And between the new rules of magic, and Buffy's resolution that she and the Scoobies will be the arbiters thereof, being a pretty good arc for the series, and the fact that Ms. Summers seems to have finally gotten her act more or less into gear, it's a good time to be a Buffy fan.

Finally, I'd like to take a moment to say that based on the first two issues of Sir Edward Grey, Witchfinder's new miniseries "The Mysteries of Unland", Kim Newman – writer, critic, author of the Anno Dracula novels and officially one of the best dressed men in journalism – needs to write more comics. I don't even care that I'm completely biased – the guy is a legend, and he fits this particular expanse of Mike Mignola's Hellboy universe like a glove.

In collaboration with co-writer Maura McHugh and artist Tyler Crook, we get a murder mystery set in a Victorian West Country village (complete with ropey accents) involving a patent medicine factory, a suspicious drowning and an unsettlingly emphasised presence of eels. Imagine if you will H.P. Lovecraft's The Shadow Over Innsmouth if instead of featuring inbred frogmen and eldritch abominations, it featured parasitic lungworms, murderous giant eels and a cultist conspiracy focused on the draining of the local swampland.

Whilst I wasn't overly familiar with Sir Edward Grey prior to reading – in the process of researching it turns out that he's been around since the "Wake the Devil" days – in practice he shares just enough connective tissue with the majority of Newman's protagonists to soften the bump, whilst carrying off a snarky wit that's usually absent from them. Newman's well-earned reputation as the most knowledgeable writer on the subject of horror in Britain, and his status as an untapped resource in the field of comics, stands him in good stead for what's shaping up to be a real page turner.

Well, that's it from me for this week. I'm Adam X. Smith, and I wish I was a wild west hero. Not sure why – maybe I've been listening to too much ELO.

*I know this is sort of a leftover instinct from the show – where Joss Whedon would habitually treat every season finale as a potential point of no return right up to the point where he actually did kill off Buffy before the show moved to a different network – but really? Okay, no big deal – just a pet peeve.

Adam X. Smith is a paranoid android from the Planet X. For the last 27 years he has been living amongst the people of Birmingham, England (and more recently the University of Lincoln) ostensibly as a student of the school of hard knocks (also BA Hons Drama), but secretly on a mission to scout out the planet for invasion by alien forces; his weekly communiques on his various blogs are actually highly coded messages to his extra-terrestrial masters. He enjoys the musical stylings of local chiptune-metal band Elmo Sexwhistle, the fiction of Kim Newman, Kurt Vonnegut and Chuck Palahniuk, and his hobbies and interests include film-making, drama, occasional Youtubing, journalism and plotting the subjugation of humanity. He can be found on Youtube, Tumblr, Twitter or by jamming an ice-pick through the optic chiasm.

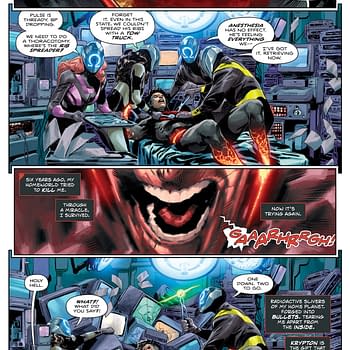

Low #1 (Image, $3.99)

By Graig Kent

There are apocalyptic stories and there are end-of-the-world stories, and though stalking similar ground, they're not exactly the same. While both are steeped in death, a story of an apocalypse tends to be about the cause and about surviving, about fighting and triumph and sacrifice. An end-of-the-world story tends to be a more low-key affair, about acceptance, about finality, and sometimes the chaos and madness that occurs along the way. The apocalypse can become post-apocalyptic, of survivors and new terrain,, whereas the end-of-the-world literally means the end.

Low, the new Image series from creators Rick Remender and Greg Tocchini, sits in middle ground between the two, as the distant future Earth on display finds the remaining members of humanity (a few million) long having moved deep beneath the surface of the ocean to escape the deadly radiation of an expiring sun. Humanity is on its last legs, though this underwater civilization, the city of Salus, is an extremely comfortable habitat, full of technological and architectural marvels.

The story centers around the Caine family. Stel, the matriarch, is relentless in her search for another home among the stars. She monitors the reports returning from deep space probes launched centuries ago and remains optimistic that there is a solution to salvation. Her husband, Johl, is a realist, more than aware it will all be ending soon, but in the meantime, things need to get done, as what remains of life still carries on. He's the operator of the last remaining Helm, a weapon in the form of high tech armor programmed to respond only to his family bloodline. He's excited to take their young daughters, Della and Tajo, out into the open water to train them to one day take the Helm. Their son, Marik is content being a grease monkey repairing subs.

Low gets off to a fairly slow start, with Remender taking his time in establishing the world, its sense of history and it's encroaching end, and how that inevitability affects the civilization, as seen through the eyes of the Caines. There's a calming, comfortable status-quo at play, of lives moving onward and the worry about the doomed sun no greater than the worry about sustaining food supplies or the general operating conditions of the submersible fleet. It's a concern, but it's also their reality. In the backmatter, Remender talks of personally finding his own optimism, and how that is reflected in the book. It's a welcome message in a future fantasy, one that is mid-end-of-the-world and post-apocalyptic, that not only is there hope, but that things can be all right in the present, even when in the grandest scope they're not.

Of course, Remender builds all this up, especially the wellness of family, simply to tear it down in the book's second half. It's enough to have a futuristic society dealing with the looming end of the world, but there also have to be those who don't care. As the Caine family is out on their Helm training, they are attacked by the Scurvy Horde, a pirate society living outside of the safe sphere of Salius, and desperately wanting in.

The story takes on a whole new facet with the introduction of the Scurvies. There's a class distinction here, of the haves and have nots. Where you have one seemingly harmonious, prosperous even, society that's focused on the survival of humanity, there's a whole other society eager to survive at any measure, to get into the domed city to make a home, to win a fight only they're really concerned with, not realizing there's bigger issues at hand. The glories and spoils of petty, narrow minded, selfish men. The fight of the Scurvies may be born of legacy but there's no real interest in moving beyond long ago grudges. They are generally, an uneducated, violent, crass lot, out to reap what they can through might and numbers and whether they're aware of the world's end is unsure, it's certain they don't care.

But you look at any culture that's poor, oppressed or mired in war. There's no concern over the environment, there's no worries about space or shark finning or the global economy. It's all about the survival and/or satisfaction of self. The Scurvies are the enemy of the story, by their violent nature, but I won't be surprised at all if Remender has more complexity in store for them.

As noted before, Low is a challenge to start because of its establishing pace. This isn't helped much by Tocchini art, which can be difficult to interpret at times. Foreign landscapes, environments, and technology are all that much harder to resolve when the artist doesn't have a definite line that accentuates and separates the details. The scratchiness of his work is impressionistic, but what holds and binds the visuals together is his deft color palette. With his use of vibrant yellows, soft oranges and greens, Tocchini helps build Remender's optimistic future. There are no heavy shadows, no murky browns, no oppressive grays here. Tocchini uses stark reds to highlight danger and violence but always leaves a touch of vibrancy around the Caines amidst this.

Ultimately, while some panels can take a few passes in order to fully comprehend the detail therein, so many of the panels are worth exploring, some quite breathtaking. Tocchini has crafted a wonderfully realized world, his ships inspired by aquatic life are fabulous, and his design of Salus both in and out are marvelous, though we only catch a glimpse of both with any sense of scale.

Even with the slow-ish start, it ratchets up incredibly to a taut, gut-punch of an ending, sinister and severe. Once you reach the end, you kind of forget about the end of the world a bit. There are more important things at hand, and the coming issues are eagerly anticipated.

Graig Kent keeps promising to finish the final edit on that novel, play test that board game, start drawing that web comic, find an artist for that children's book, and maybe write that teleplay, but first he's got to read that pile of comics and watch that backlog of movies…and that dog won't walk itself. He's been reviewing things for over 15 years. He's rarely on twitter @thee_geekent, he sometimes writes about movies at [wedisagree.blogspot.com], and his dog has a blog [tacomblur.tumblr.com]

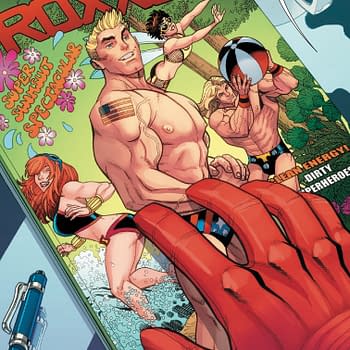

Hawkeye #19 (Marvel, $2.99)

By Jeb D.

One curious effect of the increasingly frustrating delays between issues of what has been arguably Marvel's best comic for the past few years is that issue #19 arrives just a week after #11 picked up the Eisner award for Best Single Issue, and this current comic bears more than a slight resemblance to that adventure of "Pizza Dog": once more, writer Matt Fraction and artist David Aja offer a largely non-verbal storyline, with readers required to use Aja's brilliant visual signposting to follow the action. Like #11's "Pizza Is My Business," Fraction and Aja use a variety of visual tricks to convey the difficulty of confronting the world in isolation; this time, though, it's not a dog, but Clint himself who's forced to take on the "outsider" perspective.

The Barton brothers are recovering from the latest of their (seemingly interminable) encounters with the tracksuit-wearing gangsters: Barney's in a wheelchair, and Clint has lost his hearing (for the third [?] time IIRC), deepening and underlining the isolation that he's battled since the series' beginning. And just as readers had to follow Lucky's (AKA Pizza Dog's) investigation through visual cues, and the few words that Lucky himself could understand, for this issue, Aja and Fraction have matched their previous effort, coming up with a dizzying assortment of clever ways to approximate Clint's state of temporary deafness, including empty word balloons, fractured text (where he's doing his best to lip-read), and infographic-style representations of American Sign Language.

But that's where things get a bit dicey.

A digression: I grew up very close to a grandfather who was completely deaf. His family did not have access to ASL instruction for him when he was young, so they devised an alphabet-based sign language (as opposed to the word-and-concept approach of ASL) which, so far as I know, is today a "secret code" known only to his grandchildren. He lived what most of us would think of as a fairly "normal" life: married a hearing woman, had kids, and worked most of his life as an auto mechanic; everyone in town knew him, and though I don't think anyone outside the family ever mastered our sign language, he was able to communicate with his neighbors and customers. In other words, he assimilated himself into a society that proceeded on the assumption that his deafness was something to be overcome, which was pretty much the standard view of his condition in those days.

Times change, though, and in the years since my grandfather's passing, we've seen the emergence of a unique culture among many who share his condition, who regard deafness not as a "handicap," but as a specific and distinct way of interacting with the world. As a result, the juxtaposition of the Pizza Dog story, with one that attempts to convey the experience of deafness, is in some ways an uncomfortable one. Just for starters, there's no one who can definitively say that the team did, or did not, accurately convey the experience of a dog listening, and reacting, to humans; but there are certainly plenty of people with first-hand experience of living deaf in a largely hearing world, for whom this either will or won't ring true, regardless of how it reads to the rest of us. And while Lucky was encountering cues and signage that occurred naturally in his environment, the ASL representations here serve more as "text boxes," that stand apart from the action, giving them a slightly artificial quality (I also have no idea how accurate or effective they might actually be). I'm certain that Fraction and Aja did their research (and I have no idea how much personal connection they may have with deaf people), but this is a bit different than, say, writing an issue with no scripted dialog at all: like it or not, they're outsiders paying a temporary visit to a culture whose experiences they can only approximate (the fact that Clint's deafness is described as "hopefully temporary" reinforces that).

This isn't to say that Fraction and Aja shouldn't have attempted this at all: rigid requirements of cultural or sexual specificity in creating comics would eventually lead us to situations where a cast of mixed genders or ethnicities would require separate writers and artists for each individual character. In fact, one of my favorite current series, A Voice in the Dark, features a cast that is principally made up of conventionally-abled women of color… written and drawn by an arthrogryposic white male. And on that basis, I think we should cut Fraction and Aja slack on the question of cultural appropriation: there is definite usefulness in any attempt to break readers out of their normative perspectives, and from the point of view of a hearing reader, this comic succeeds. But I wonder if either of them (or colorist Matt Hollingsworth or letterer Chris Eliopoulous or editor Sana Amanat) considered bringing a deaf creative collaborator onboard for this issue.

As Fraction detaches himself from his Marvel superhero work, Hawkeye is winding down, with only three more issues remaining, and while it's given us some fantastic reading, the recent bifurcation between the Clint-centric stories, and those focused on Kate Bishop, has exacerbated its pacing problems (although I've found the recent Kate issues, with art from Annie Wu, a nice change from Clint's troubles with the "bros"). But I can't gainsay the amount of creativity, hard work, and good intentions, that went into the creation of this issue. It's going to be a shame to see Hawkeye end, but issue #19 makes it clear that Fraction and Aja aren't coasting on their way out.

Jeb D. is a boring old married guy whose comics background includes attending the very first San Diego Comic-Con, being lectured on Doc Savage by Jim Steranko, and fetching an ashtray for Jack Kirby. After a quarter-century in the music biz, he pursues more sedate activities these days, and will certainly have a blog or Facebook account or some such thing one day.