Posted in: Comics, Vintage Paper | Tagged: Frederic Wertham, karl marx, le grelot, paul lafargue, the issue, vladimir lenin

THE ISSUE: Fredric Wertham's Hero and the Third Republic

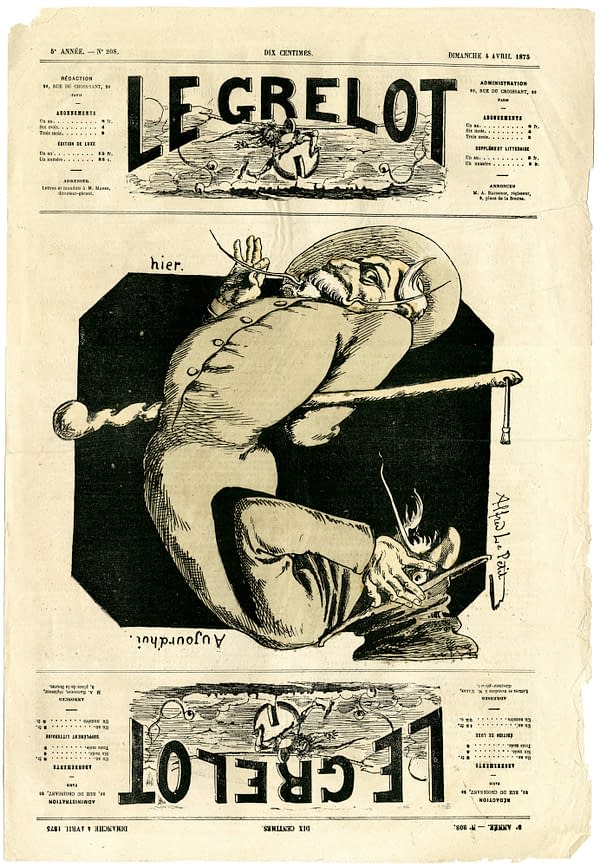

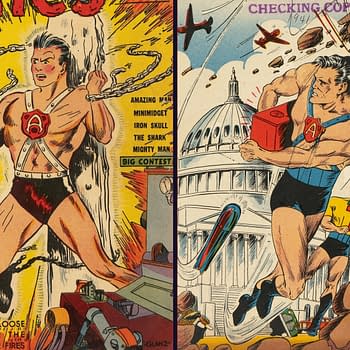

Welcome back to a post-revolutionary edition of The Issue. At issue today is Le Grelot No. 208 from April 4, 1875, with cover art by Alfred Le Petit. This one caught my eye for further study due to its usage of the now-familiar "flip cover" technique, complete with flipped logos and cover dress. What could have inspired such a thing in France in 1875? I'm fairly well grounded in 19th century American history, but 19th Century French history…? Not so much. So this issue of Le Grelot gave me a good opportunity to brush up a bit. As it turns out, the text that accompanies the cover illustration gives us our hook into understanding this history — after a fascinating detour into 20th century comic book history via Fredric Wertham. It reads: Yesterday / Today.

The Issue is a regular column about vintage comics and other vintage periodicals from throughout world history. The idea behind The Issue is simple: for each post, I'll choose something from my collection and talk about what's going on in it, and discuss the publishers and creators behind it. And essentially I'm just going to end up stepping through comics history one issue at a time. There is just one rule in The Issue: No recent stuff. Everything will be from before 1940, and most of it will be from before 1920.

Both figures depicted on this flip cover illustration are the same person — Patrice de Mac Mahon, who was Chief of State of France 1873-1875, and President of France 1875-1879. This of course gives us a clue as to what this is about: the defeat and capture of Napoleon III and his entire army in 1870 during the Franco-Prussian war triggered a collapse of the old French government and the declaration of what is known as the Third Republic of France. But with no surrender offered by France, German forces proceeded towards Paris. French government officials withdrew from Paris to keep the fledgling government intact and to mount a defense — while negotiating peace.

Here comes the plot twist: with Paris on its own and under siege by Germany, a group of radical socialists called the Paris Commune seized power in the city and took control of Paris. They held power only briefly, but it took time for the Third Republic to stabilize and coalesce after all this. France's new Constitutional Laws were being passed in 1875 as this issue of Le Grelot hit the streets. Le Grelot was launched in 1871 at the dawn of the Third Republic. It was an "anti-Communard" comic paper, or as they said in France then, a Caricature Journal (or Caricature Paper). Notably, caricature was subject to France's 19th century version of the Comics Code during most of the period 1820 – 1881 — it was subject to strict guidelines and had to be pre-approved before publication. This was administered by the interior ministry of the government, with no appeals accepted, and no explanations given.

A man named Paul Lafargue played a role in the Paris Commune, and in the "Communard" agitation tactics that led up to that moment in 1871. You might have heard Lafargue's name mentioned in more recent comic book history in America. If you have, you might have seen him described as "a physician who happened to be married to Laura Marx" — he is the person for whom Fredric Wertham named his NYC psychiatric clinic, the Lafargue Clinic.

That description is wrong in every regard — except for the part about being married to Karl Marx's daughter Laura, which he certainly was. Lafargue was an ardent disciple of Karl Marx, who moved him around Europe like a pawn. Lafargue was also a very good propagandist and agitator. He was never a practicing physician, and had no faith in modern medicine. That led to a rather bizarre moment in this history, as with France reeling from war and rebellion, LaFarge's father still felt compelled to write Karl Marx to complain about his son's lack of diligence in pursuing his medical career. This in turn led Marx writing to Paul in France, where Lafargue was playing a role in the Paris Commune, and was a signatory of the infamous "Red Poster" that paved the way for it. When Paul and Laura Lafargue completed their suicide pact in 1911, Vladimir Lenin traveled to France to eulogize them. He said in part:

[We in Russia] who have had the good fortune, through the writings of Lafargue and his friends, directly to draw on the revolutionary experience and revolutionary thought of the European workers—we can now see with particular clarity how rapidly we are nearing the triumph of the cause to which Lafargue devoted all his life.

In Europe, too, there are increasing signs that the era of so-called peaceful bourgeois parliamentarianism is drawing to an end, to give place to an era of revolutionary battles by a proletariat that has been organised and educated in the spirit of Marxist ideas, and that will overthrow bourgeois rule and establish a communist system.

This is not obscure history… except among comics historians. Lafargue, a radical Marxist revolutionary who worked to destabilize the governments of France and Spain, and who made Lenin believe that "a communist system" could be established around the world…and incidentally, had no faith in modern medicine… was a curious choice by Frederic Wertham for naming his psychiatric clinic in Harlem. Unless perhaps he had similar ideas himself, of course. And wasn't all that interested in pursuing serious medical research, either.