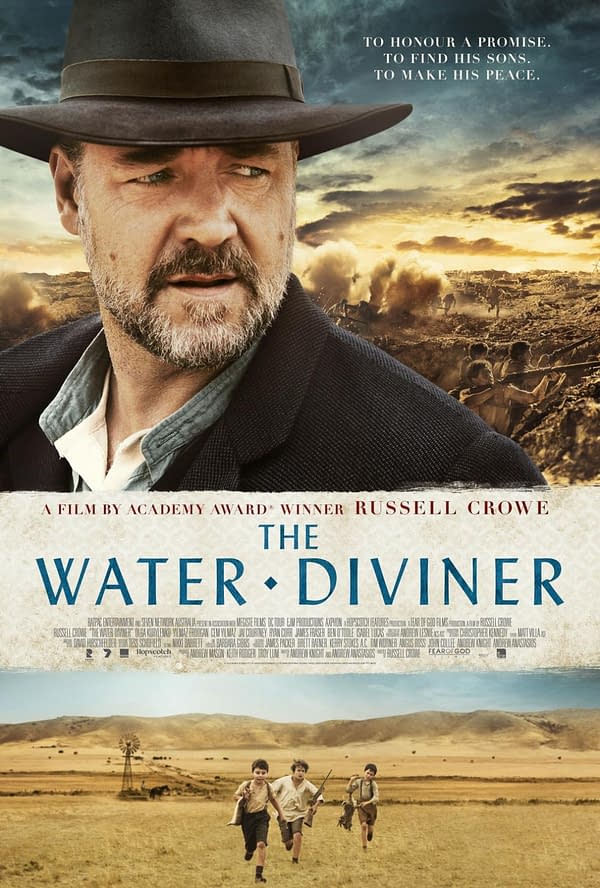

Posted in: Movies | Tagged: Andrew Lesnie, entertainment, film, olga kurylenko, russell crowe, the water diviner

The Water Diviner – Visually Stunning, Ultimately Hollow

By Chris Maltby

The film opens with an interesting sleight of hand; as an officer dresses and prepares for battle the western viewer typically assumes that they are witnessing the preparations of someone fighting on the more culturally recognizable side. When it is revealed that we are watching Yilmaz Erdogan's stoic Maj. Hasan prepare for what seems to be a decisive battle, in the closing days of Gallipoli, it momentarily flips expectations on their heads, allowing the audience to suppose for a moment that they will see something different than expected, that the film may yield a more interesting and contrary perspective than was expected.

What is surprising is that Crowe, an industry veteran of countless years and even more productions could spend so much time in the business and produce something so emotionally tone deaf and inauthentic. The death of both his wife and three sons seems to register with the character only fleetingly, before becoming something of a generally advertised standard for why he's doing what he's doing. Moments that should resonate emotionally alternately fall flat or grossly overplay their hands. This overall sense of inauthenticity culminates in a musical scene midway through the film that feels less like an organic moment than something recorded for release on a Starbucks exclusive Putumayo CD.

This subtle fishing for a substitute wife and son crescendos in a late night dinner between Kurylenko and Crowe that is set in a room with enough lit candles to burn Istanbul to the ground. However, the scene is visually sumptuous, and cinematographer Andrew Lesnie's work throughout the film is phenomenal. What the film lacks in narrative substance is inversely proportionate to how visually sumptuous it is. Lesnie imbues the film with golden hues and amber tones, incorporating bountiful vistas with a gorgeous palette that is constantly arresting and almost decadently rich. Through Lesnie's camera, western Australia is alive with sunsets of burnt umber and rolling ochre plains; his Istanbul is a riot of color that would make Tarsem blush.

By the time the film's third act rolls around the audience should be able to predict with unerring certainty the ultimate outcome of the film, which while visually bountiful, is an ultimately hollow vehicle seemingly executed to appease it's directors notoriously self indulgent ego stroking.

Chris Maltby is an NYC based street walkin' cheetah with a heart full of napalm.