Posted in: Comics, Recent Updates | Tagged: andrew wheeler, Comics, no more mutants

No More Mutants #5 by Andrew Wheeler – Superhuman Disabilities

One of the defining characteristics of superheroes is that they are people who can do more. They can fly, or read minds, or punch through walls. Even if they have no superpowers, they still have peak abilities, and they still go out and fight crime. They do things that you and I cannot do.

In that context, people with disabilities are a minority group that you may not expect to see well represented in superhero comics. Disability, as defined by the World Health Organization, is about impairment, limitation and restriction. In that sense, people with disabilities are people who can do less.

I'm aware that this is an over-simplification that doesn't represent individual experiences. In many cases disabilities are only limiting because we build our society to suit the majority. However, in the broadest and most impersonal terms, superhuman ability is the farthest extreme from real life disability.

At last year's San Diego Comic-Con, Andrew Imparato, the president of the American Association of People with Disabilities, told the Los Angeles Times why superhero stories seem to resonate with a disabled audience. "There are a lot of disabled people who just want to be who they are and not have to change themselves to fit into society. … And a lot of people with disabilities like to have a fantasy life. If you're a disabled person – on disability, living at home – it can be pretty depressing and isolating."

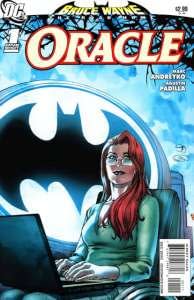

The genre does not lack representation of people with disabilities. Though the numbers are not great, there are three very high profile heroes with major physical disabilities – Daredevil and Professor X at Marvel, and Oracle at DC. (There are also a great many characters with mental disorders, but I'll talk about that in a future column.)

Yet do any of these characters really represent people with disabilities? After all, these heroes are always compensated in ways that real people with disabilities are not – and sometimes in ways that may seem provocative or insensitive. In real life, people who have lost a limb or are born without one do not get powerful cybernetic replacements, like Forge, Sasha Bordeaux, Misty Knight, and too many others to name. Iron Man's suit is better than any artificial heart, and can we really say that Daredevil represents blind people when his radar senses allow him to 'see' better than most of us? He uses his stick to swing through the canyons of Hell's Kitchen, not to navigate the sidewalk.

Yet Oracle is also the clearest example of the incongruity of disability in a superhero/super-science setting. Batman suffered a broken back at the hands of the villain Bane, but went on to make a remarkable recovery. Damian Wayne had his spine replaced after he suffered a similar injury. Over at Marvel, Professor X has stepped out of his wheelchair on more than one occasion for all sorts of contrived reasons – though he always ends up back there in the end.

Current medical science could not restore Barbara Gordon's spine, but in superhero comics even death is not forever, so spinal injury could be an easy fix. Superhero science could restore her, and many fans believe that she should be restored. Some creators have even pitched stories to make it happen. Alex Ross says that his pitch was rejected precisely because of Gordon's perceived value as a disabled superhero. DC editorial wants the character to resonate with readers with disabilities – and perhaps they recognise that it would infuriate and insult readers with disabilities if they were to restore her.

As tempting as it is to say that it doesn't make sense that Barbara Gordon will never walk again in a world of magic and super-science, this is the world that superheroes exist in; one where every problem might be solved by punching the walls of reality or making a deal with the devil, but it's not a very good story if they are. The paralysis of Barbara Gordon is Oracle's origin story, and if you undo the origin, you undo the character.

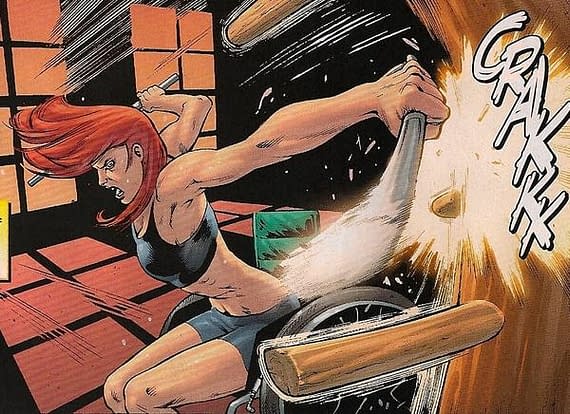

Oracle remains an exceptional figure in superhero comics. Her wheelchair does not fly or shoot lasers, and she cannot physically chase villains across rooftops (though she probably can chase them remotely with her advanced super-tech). She has not been given superhuman powers that nullify her disabilities; she has had to overcome her limitations through intelligence and will. It's a rare but empowering story.

As for those other heroes, the Daredevils and the Iron Men, perhaps it's not so incongruous that their superpowers allow them to transcend their disabilities. After all, most of us appreciate the idea of a fantasy life – it's why we all read superhero comics. The fact that superheroes with disabilities can do things that real people with disabilities can't do is consistent with all our experiences. The rest of us can't do the things that Daredevil or Iron Man can do, either.

These characters offer an escapist fantasy that readers like Andrew Imparato clearly appreciate, and that value should not be ignored – but they are no substitute for a character like Oracle, whose experiences are more representative of real people with disabilities.

Andrew Wheeler writes about food and comics and gaiety. Sometimes simultaneously. He is the author of Eat Britain!