Posted in: Comics | Tagged: Alan Moore, British Library, Comics, comics unmasked, entertainment, paul gravette

The British Library Vs. The Sunday Times Over Comics

Today's Sunday Times has a review by Waldemar Januszczak of the Comics Unmasked: Art And Anarchy In The UK exhibition, currently on display at the British Library. And he's not happy. On Friday I went to a talk by the curators Paul Gravett and John Harris Dunning looking through the exhibition for the audience talking about their decisions and obsessions. I thought it might be interesting to compare and contrast the two. Waldermar's comments in red… it seems appropriate.

But first Gravett and Dunning talked about the choices they had to make and the story they wanted to tell with two hundred and twenty objects. That there was a danger of showing too much contemporary work, they didn't want the experience to be like going into Waterstones. They wanted to reflect the vital artistic modern scene but tell the story of its past.

For a British Library exhibition, there was an unusual amount of loans because, while the Library keeps an exhaustive collection of printed works, they didn't have original scripts or artwork. But the forty loans, just with the government indemnity scheme and insurance cost an awful lot.

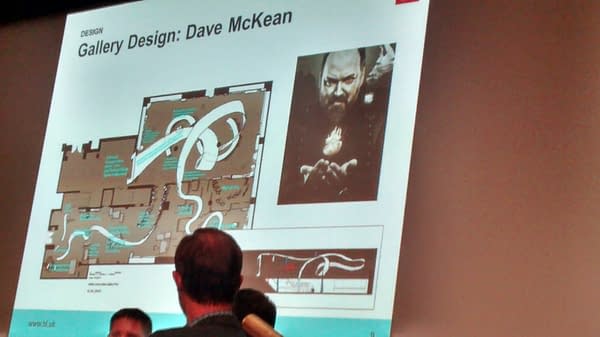

The very high ceiling, gave designer Dave McKean the chance to create a roll of paper, suggesting a stream of consciousness running above the show to its conclusion and attendees are encouraged to follow the strip. They talked about Paul Gravett coming in to the exhibition every week with a new with a carrier bag of things to display, even up to the final week.

That the dramatic entrance wasn't working so had to be totally redone six weeks before the launch, and recreated by McKean.

They wanted lurching cabinets but found the books just wouldn't stand up. Not everything Dave McKean wanted was affordable, such as the curved cases for the Social side of comics area. So they took cases for the Georgians Revealed exhibition joined up by MDF, and gave the sense of a curve. If not an actual one.

As for TV audio, much of what they wanted such as Frank Bough arguing against the existence of the Action comic in the seventies moral turpitude (years before the expose about his sex and drugs parties) no longer exists. But they did use the recording of the Oz trial, when an edition of the alternative magazine Oz edited by school children began a major obscenity trial. The audio on display has the then-fifteen year old Viv Berger being very articulate in the dock and his mother telling the court that she wasn't shocked by the comic.

Jamie Hewlett was their first choice for the posters. A big name, his work on Tank Girl summed up a period and spirit of rebellion on British comics. It was also interesting to see how he moved on to cartoons and music, with the Gorillaz being the most prominent fake band in the West "since The Archies" as Paul pipped in. Doing a second "panel" for the poster was Jamie's idea and turned the poster into a comic, and was inspired by the front and back pages of the old Giles Annuals.

The exhibition sets out its stall in the foyer of the library, where a huge poster of a sexy superheroine in hot pants, who looks like X-Girl, is taking a slug of whiskey in a dark alley. It compares itself with the famous tapestry on the opposite wall, in which Ron Kitaj reimagines Eliot's The Waste Land as a dystopian nightmare set in the shadow of Auschwitz. In their size and colour, the two images are comparable. Where they differ is in the fact that one is the creation of an intelligent adult who's read some books, while the other is teenage drivel that has poured out of a mind untouched by historical reality.

At the feet of the superheroine (created by Jamie Hewlett, of Gorillaz and Tank Girl fame) there's a heap of drug paraphernalia: some broken cigarettes used to make a joint; a few empty wraps. And at the back of her alley is her superhero boyfriend, zonked out in a junkie coma. The sight of the British Library seeking to get down with the kids as crudely as this is depressing.

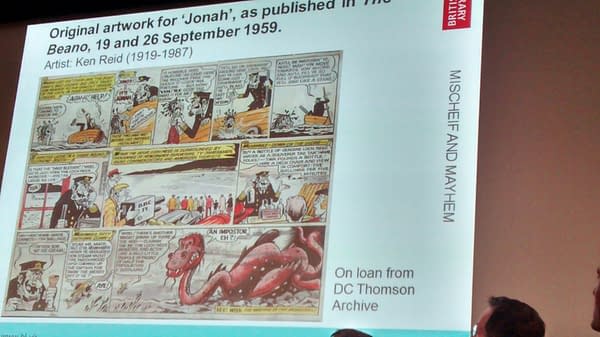

Paul Gravett revelled in the Jonah page by Ken Reid in the Beano from 1959, so much insanity in half a page of comics, being read by a million children. Although they did talk about how the page was a little illegible, having to be read in the low light necessary for preservation.

We commence with Mr Punch, the "radical scourge of all authority", whose cartoon antics were intended to annoy the Victorian middle classes. A statue of Mr Punch, which stood in the lobby of the Punch offices, is followed by a painting by Leonard Raven-Hill of Punch in a smoking jacket, smirking impishly. These Mr Punch portraits are accompanied by examples of subsequent cartoon characters who, like Punch, were notorious for causing mischief: Beryl the Peril, Dennis the Menace, Jonah, "the hapless, buck-toothed jinx from The Beano".

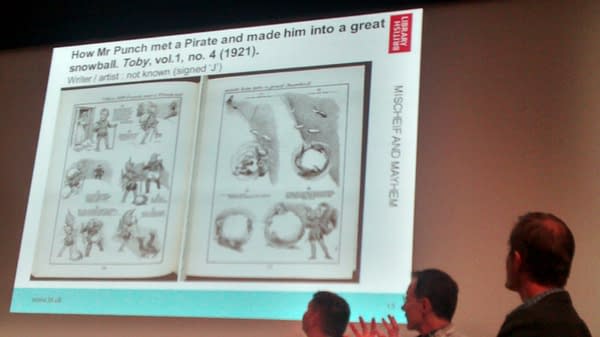

Gravett looked at how Toby magazine spun out of punch, with anarchic comic strips from 1921.

Mr Punch was indeed a notable comic character, but his origins lie in Italian theatre, in the commedia dell'arte and the notorious Neapolitan scoundrel Pulchinella. In Britain, he belongs more actively to the history of the seaside puppet than the history of the comic book. Even in Punch magazine, he appeared most often in single cartoons. The defining comic-book idea, of a story told simultaneously with pictures and words, barely applies to him.

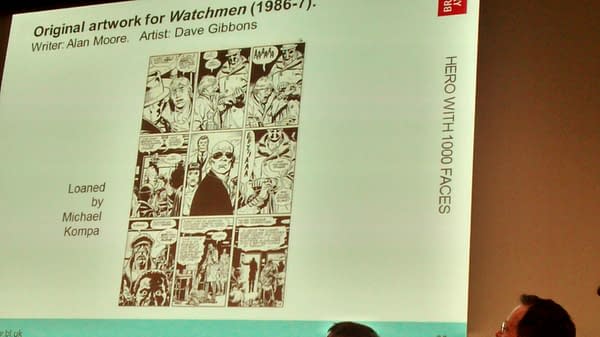

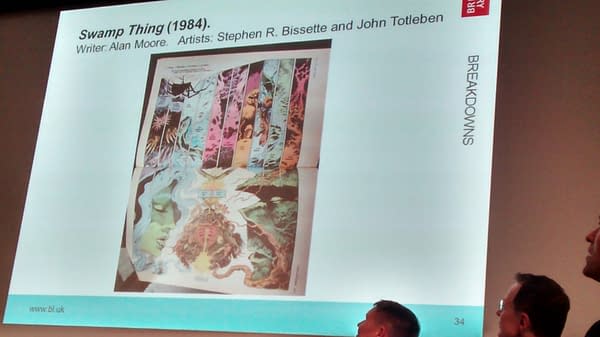

They talked about the transforming work of Alan Moore, what influenced it and what it influences, choosing a mean spirited Watchman page. They talked about his influence in breaking and smashing the page up, with a page from Young Avengers to see how that has mainstreamed, and taken an influence from gaming as well.

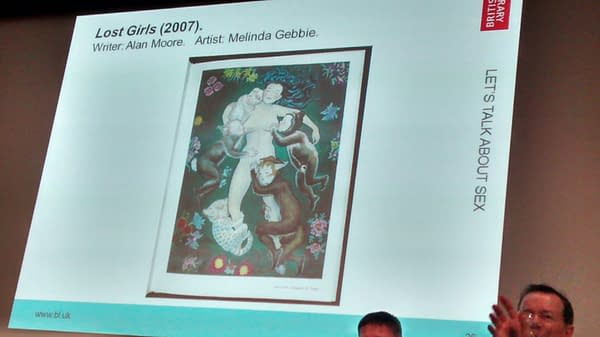

They also discussed how Alan Moore and Melinda Gebbie made a marriage out of working on pornographic comics, and how they both had similar influences but Moore has the mainstream comics success, Lost Girls was a project that saw he trying to return to his roots, a place Gebbie already inhabited.

Moore, who gets more namechecks here than Popeye had cans of spinach, sets the tone for a show fixated with the Mr Hyde side of comic art: lots of mutilation, lots of violence, lots of horror and a horrible "sex" section featuring grim sadomasochism and tied-up girls.

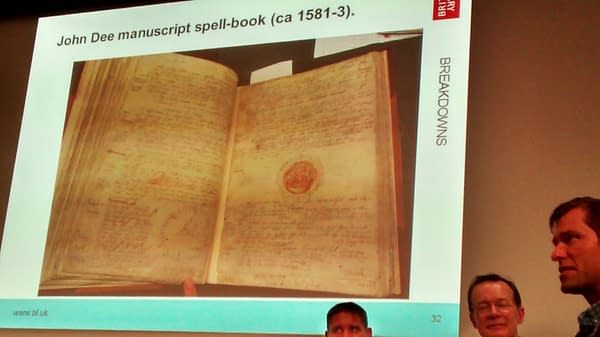

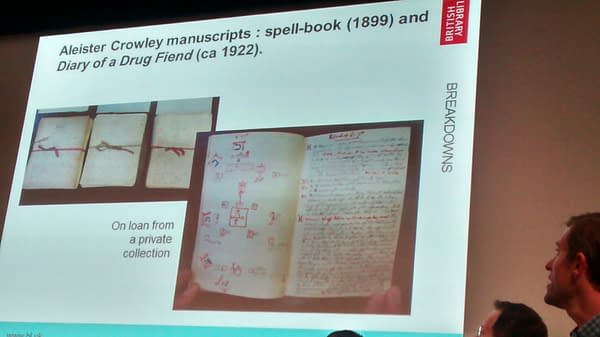

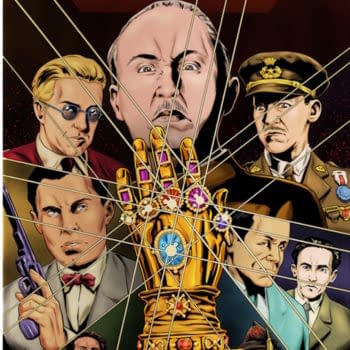

In a truly ridiculous climax, the final room is devoted to Aleister Crowley, the "Great Beast", and his passion for drugs. Apparently, Crowley's influence on the history of modern comics has been immense. Moore, who describes himself as a magician first and comic-book writer second, is a follower of "the Magus" and shares his appetite for magic mushrooms and occult realities. Quite how the British Library, the fount of so much reason, ended up devoting this much space to this much unreason is beyond me.

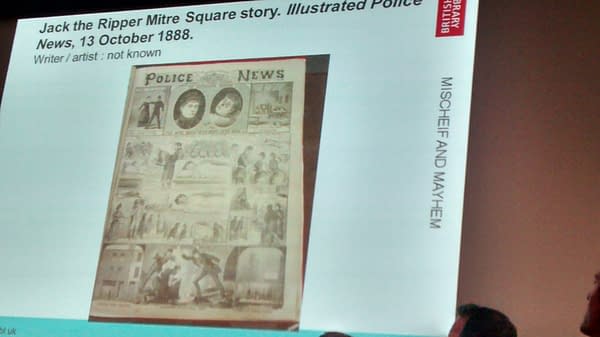

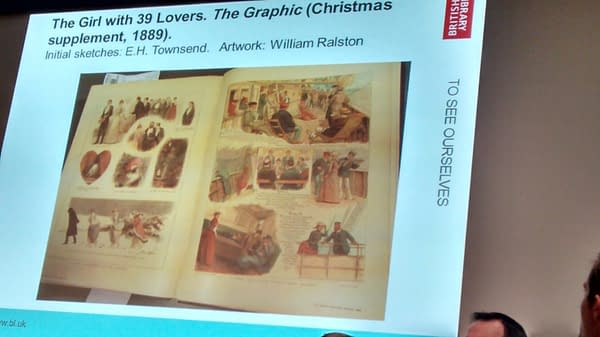

Illustrated Police News from 1888 was one of a number of publications, including The Graphic that took news stories or people's experiences and retold them in comic book form, almost a century before biographical or journalist comic books would become popular, and well before the US had The Yellow Kid.

Tales From The Crypt, the UK edition with a warning that it was not for children printed on the cover unlike the US edition, nevertheless it was a subject for outrage in the House of Commons and horror comics were banned in the UK in the fifties,

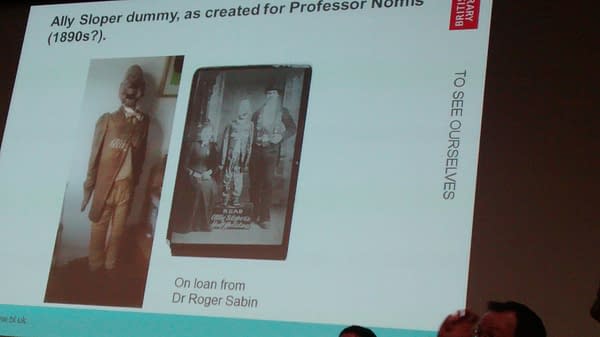

Described as "the Spider-Man of his day" by Gravett, Ally Sloper was a comic book drunken wastrel character with a half a million a week readership, who saw two spinoff films and a ventriloquist act on the stage. The ventriloquist dummy on display is stuffed with newspaper for paper mache… one of which is the Temperance Society Chronicle…

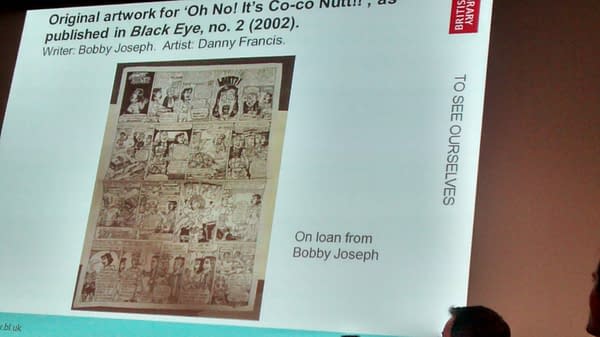

They highlighted Black Eye, a black version of Viz Comic from 2002, tackling black British issues in an incredibly irreverent way, from Bobby Joseph, who has previously been sued by athlete Linford Christie when a previous comic, Skank, alleged he took drugs. Christie would later be banned from competitions after testing positive for anabolic steroid nandrolone.

There was the Glasgow Looking Glass, billed as the world's first comic book, aimed at adults with speech balloons, strips, and continuing characters… and a satirical look at local politics that ran for 19 issues.

Action Pact from the Anti Nazi League gave advice on how to fight the National Front and deal with the police, but also gave a superhero teamup The Justice Brothers, fighting fascism with their fists.

Catalogue images were used to create comic books intended to subvert the original form, such as this front page from International Times.

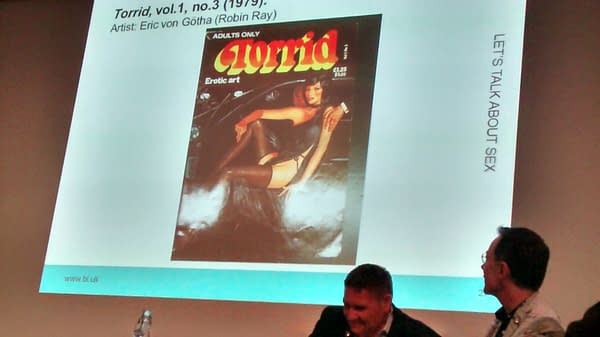

They talked about a velvet underground distribution of erotic comics featuring S&M material, retelling personal experiences and distributed through mail order in the UK and US, often from female writers and artists.

An early example of the fight for creator's rights, Torrid was a seventies fully painted sexually explicit comic that by an ad man. Erich von Gotha was told by his publisher that this would be the closest many of his audience would come to having sex. However he discovered that the same publisher was selling the rights and the original art to France without telling or paying him so…. he moved to France and gained much more open success.

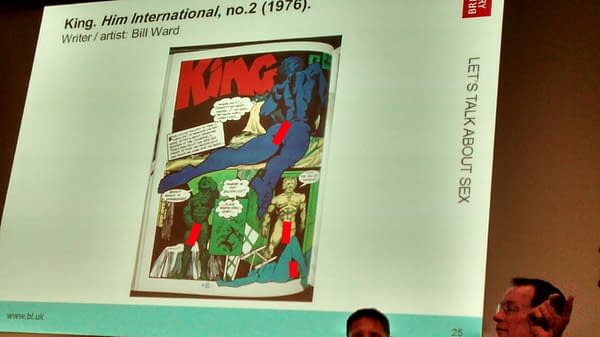

There was a lot of love for porn crime thriller King by Bill Ward in gay porn magazine Him International. Tens of thousands of copies of the magazine were seized and burnt however. Ward died of AIDS but a fan of his has collected an archive, with a plan for a retrospective exhibition and reprinting of his work.

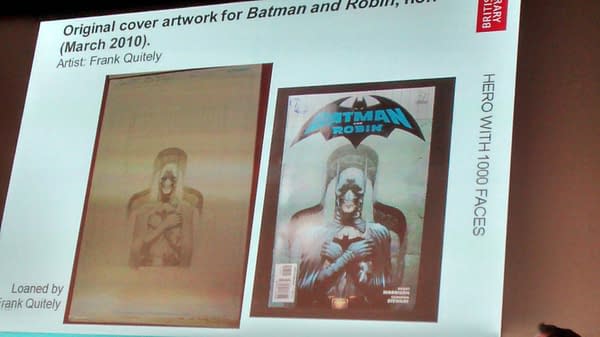

And then there was this Batman cover, described as a beautiful object and pulled out of his studios's shelves by Frank Quitely.

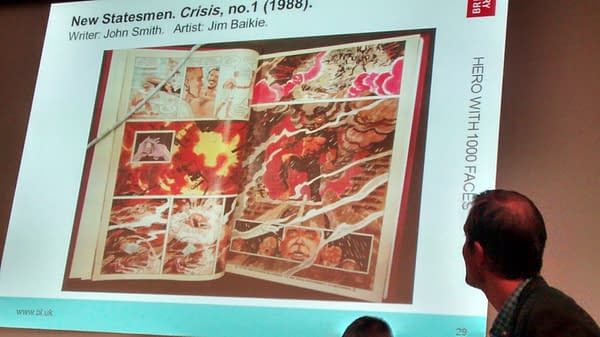

Crisis in New Statesman here portrays a superhero picking up men in a sauna before killing a bunch of Christians. Dunning, growing up in South Africa faced a media ban on anti-apartheid messages but comics such as Crisis with such messages made it through, because no one dreamed that there would be anything problematic in comics.

Also, on that point, I know of Spitting Image videos made it through for similar reasons. Including "I Never Met A Nice South African…"

So… what do you think? Are these the naughty little schoolchildren of the Oz trials as the Sunday Times may paint them? Or the curators of comic anarchy as they might see themselves?

Comics Unmasked runs at the British Library in London until August 19th.