Posted in: Comics, Vintage Paper | Tagged: civil war, Saturday Evening Post, story papers, the issue

THE ISSUE: Infernal Machines in the Saturday Evening Post of 1881

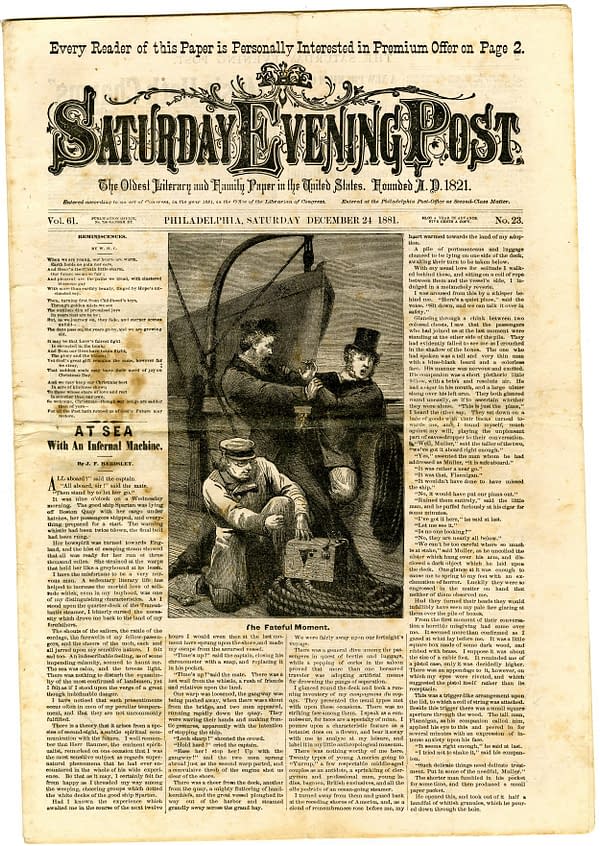

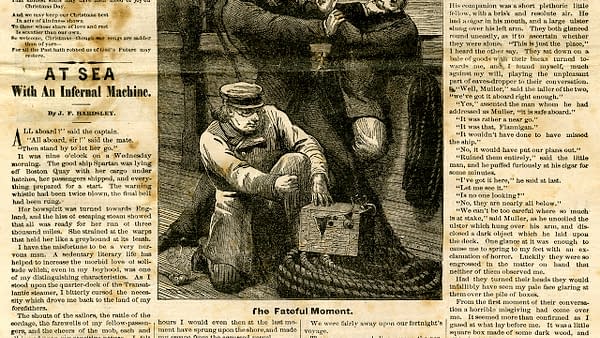

Saturday Evening Post Volume 61 #23, December 24, 1881 features a fictional story called At Sea with an Infernal Machine, by J.F. Bardsley. An "Infernal Machine" can mean a few different things but figuring out what it meant in this particular context led me to one of the most fascinating backstories I have researched in recent times. The Issue is a column about vintage comics and other vintage periodicals from throughout world history. The idea behind The Issue is simple: for each post, I'll choose something from my collection and talk about what's going on in it, and discuss the publishers and creators behind it. And essentially, I'm just going to end up stepping through comics history one issue at a time. There is only one rule in The Issue: No recent stuff. Everything will be from before 1940, and most of it will be from before 1920.

At Sea with an Infernal Machine begins with a ship departing from America, bound for the UK. But soon, the hapless hero of the tale accidentally discovers furtive men who have possession of a mysterious device. Exactly this scenario had made headlines around the world during the summer of 1881. Six Infernal Machines — Nitroglycerin-based explosive devices with timing triggers, in this case — were discovered aboard American ships heading for Liverpool in June and July 1881. That year marked the beginning of what is known as the Fenian dynamite campaign of 1881-1885. This history reverberates through politics and pop culture to this day. It also prompted the beginning of the British Special Branch.

This is fairly well-known history, but diving into some of the fine details surprised me. I'll preface this by saying that one suspects that there is disinformation among these details, so it is to be viewed with appropriate skepticism. One wonders at the outset why the purported inventor of these particular devices was so forthcoming with details when approached by the press. But Peoria, Illinois "gasoline lamp contractor" P.W. Crowe not only admitted that he was the originator of these devices on behalf of Fenians in America, he also had a historically fascinating story to tell in the process.

James McClintock After the Civil War

By way of explaining why the Infernal Machines were created, Crowe claimed that in 1880, a man named George Holgate had come into possession of one of inventor James McClintock's submarines. Holgate and some associates were essentially arms manufacturers and dealers of that era, while McClintock was the primary developer of the Confederacy's submarine technology, among other things, and a figure of some mystery. McClintock had begun working with Holgate by the late 1870s, and in 1879 the press reported McClintock had been killed while experimenting with underwater explosives in Boston Harbor. Notably, there was some initial confusion as to whether McClintock or another man had been killed in this incident, and there are more recent theories that suggest he may have actually survived that mishap — and that he may also have become a British agent in 1880.

By 1881, Crowe was suggesting that McClintock had died during experiments with a submarine and that his associate Holgate had refused an overture from Spain to acquire it. Holgate claimed that "the boat would blow up any vessel in the British fleet, and could blockade any port, regardless of all the men-of-war in the world. It would cost about $20,000 to build it", and he would place it at Crowe's disposal. He further asserted that the boat "would do more good for Ireland and fetch the British Government to terms quicker than half a million men."

They abandoned this plan in favor of the Infernal Machine scheme, as the devices could apparently be built for $25 each.

McClintock's technology was likely far from the only Confederate-era tech that made its way into the wider world in the subsequent era. Some claim that John Maxwell's "horological torpedo", a time bomb used against Union headquarters in Virginia in 1864, was the technological origin and inspiration for the time bombs (including Crowe's Infernal Machines) used for terror both domestically and abroad in the subsequent decades. As Fenian and Illinois Congressman of this period John F. Finnerty noted at the time, "one skilled scientist is worth an army." Of course, this has frequently proven correct — and the notion of war-era inventors and their technology being unleashed into the wider world after the war brings to mind generally similar circumstances after World War II.