Posted in: Comics, Vintage Paper | Tagged: charles dickens, egyptian star, fanzines, small press

THE ISSUE: Fanzines, BozCon and the Smallest Press of All

When I was researching this installment of The Issue, about The Egyptian Star: An Original Amateur Monthly, I had "The Secret Origin of Fanzines and Fandom" penciled in as the title. That captures the spirit of the thing I suppose, but it isn't quite right. There's nothing secret about this or any of the other bits of history that I enjoy posting about it. Mostly, it's more that we haven't looked hard enough, or in quite the right place, or that we think of this history (or any and all history, really) as a closed book. It's that last reason that gets to the heart of why I like each and every issue that I write about here. Opening the cover of each of these issues reveals another piece of a historical multiverse of sorts, and we as history fans have to suss out how it all fits together.

The Issue is a regular column about vintage comics and other vintage periodicals from throughout world history. The idea behind The Issue is simple: for each post, I'll choose something from my collection and talk about what's going on in it, and discuss the publishers and creators behind it. And essentially I'm just going to end up stepping through comics history one issue at a time. There is just one rule in The Issue: No recent stuff. Everything will be from before 1940, and most of it will be from before 1920.

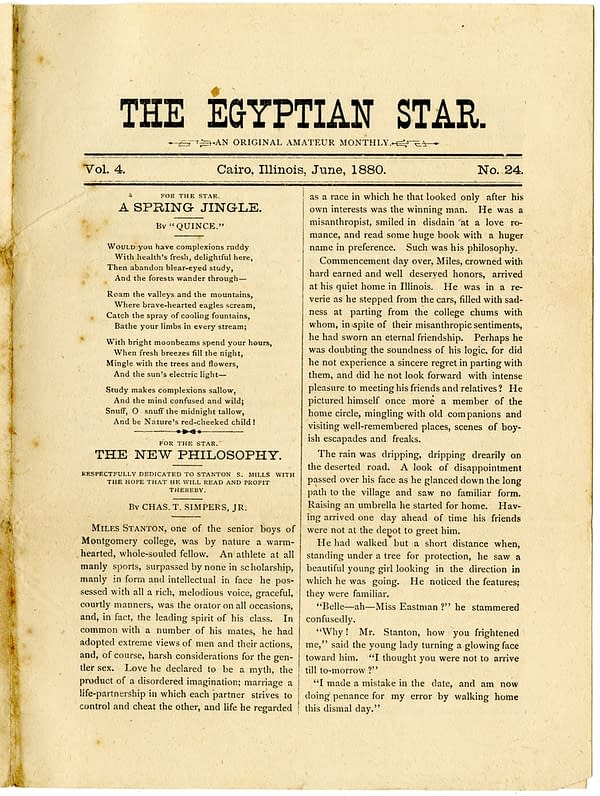

We tend to think of organized fandom as something that started in the 1930s, with science fiction pulps, and comic books a little later. Put simply, this is untrue. The realities of organized fandom — particularly a fandom centered around creating amateur publications that we would call fanzines today, go back much farther. The scope of 19th century fandom is downright amazing, and The Egyptian Star: An Original Amateur Monthly, Vol 4, No. 24. from Cairo, Illinois in June 1880 gives us the hook we need into exploring this completely-forgotten history.

One noteworthy and well-documented instance of early American fandom was the incredible popularity of Charles Dickens here in the United States. If you've ever heard the anecdotes about people waiting at the port for ships from England to bring the latest serialized installment of the current tale, they're not only true, they're just the smallest glimpse of the astonishing scope of Dickens fandom in this era. In 1842, during a planned trip by Dickens to America, a group of New Yorkers (including little-remembered but incredibly important historical publishing figure Ben Day) organized what they called the "Boz Fête", which I always think of as BozCon, because it essentially was a convention in most particulars that we'd recognize today. Famously, Dickens was overwhelmed by his American fans and hated it, and wrote about that, alas. I'm going to have to break out the full story of BozCon in another installment of The Issue, because it is truly an epic lost tale of the history of fandom.

Jumping forward to 1889, dime novel publisher Norman Munro put together an event he called a "National Convention" in New Jersey, centered around his popular series Golden Hours. He already had a fan club for this title, as did other publishers during that era. Guests at the Golden Hours National Convention included PT Barnum, Edward Ellis (the writer who launched Steampunk in America with his Steam Man of the Prairies), plus Munro's other writers and editors. The event had many of the hallmarks that we would recognize as a modern era convention. During the 1880s, 1890s and beyond, many fiction publications such as the venerable Boys of New York ran what were essentially letter columns from fans. Fans asked about old issues, they asked about continuity mistakes. They formed local groups to meet and/or swap things for their collection. They asked about how to become professionals.

Putting the 'Small' in Small Press

While there were cruder efforts for many years prior, the true beginnings of what we today would recognize as the "fanzine" era are in 1869, with the introduction of the Novelty Printing Press. I've attached some catalog pics and pricing from 1875. As you can see, at the low end, the "Boy's Job Office", the duodecimo press itself (the size of the Egyptian Star I've shown here is duodecimo, or roughly half the dimensions of a modern magazine) is $17, while the complete starter kit which also includes a typeface set, ink, and other necessary equipment goes for $32.

[easy-image-collage id=1183421]

The scene exploded. Publication content included fiction, commentary on pro publications, notice of other amateur publications, commentary on cultural or political topics, and a bit later on, even artwork. Amateur Press (sometimes called Mimic Press) participation ranged from kids to young adults. Cousin Lizzie's Little Joker was published by a 12 year old girl in New York, for example. Mimic Press publishers didn't do it for the money. They did it because they had something to show or say. They did it for the notoriety. They did it for the love of the material.

Soon, an Amateur Press Association was formed. Fan press publishers got organized. There were conventions. Then a split into East and West U.S. Associations. Then state level associations. Then rivalries between these associations. Then there were fanzines about fandom, essentially. Along with this came famous fans, and infamous fans. And "second generation" fans complaining that the first generation fans were out of touch and needed to step aside to let the next generation have a say.

At the peak of this incarnation of America's fan scene in the late 1870s / early 1880s, it's said that major U.S. cities were each producing as many as 40 or so Mimic Press publications per month. Some might recognize that time frame as corresponding with the rising onslaught of the Blood and Thunder era in dime novels. As these things usually go, fandom waxes and wanes as a close echo of the overall tenor of the times. I'm guessing that all sounds very familiar to many people reading now. Technology changes, printing methods may change. Human nature remains a constant.

And as you might guess, this stuff is very rare. "Rare" is a relative concept, so let me just say: Collecting 1960s/70s fanzines can be tough. Collecting 1930s/40s fanzines is tougher. 19th Century fanzines… barring a major collection surfacing somewhere, somehow… never say never, but… I'm a serious collector of 19th century periodicals, and I doubt I'll ever see more than a tiny handful of the "fanzines" of that era. Which means that this particular lost history might never be recovered to the extent that it deserves.