Posted in: Comics, Vintage Paper | Tagged: canadian comics, Superior Comics

Walking the Tightrope: The Wild World of Canadian Publisher Al Rucker

The road that led Al Rucker to comic publishing took a number of twists and turns, including circus acrobat, map maker, bootlegger, and muckraker.

Article Summary

- Explore the career of Al Rucker as circus acrobat, map maker, bootlegger, crime reporter, tabloid publisher and beyond.

- Learn how Rucker transitioned from Chicago crime reporter to true crime pulps and comic book ventures.

- Uncover the headline-making scandals and courtroom dramas connected with Rucker's publishing exploits.

- Trace Rucker’s contribution to Canadian comics and true crime pulps during the Golden Age.

Forrest Alfred Rucker (1889 – 1945), better known as Al Rucker during his professional career, is a little-discussed figure in the history of 20th-century periodical publishing in Canada. He is largely noted today for his brief foray into true crime pulps and comic books towards the end of the World War II era, but these endeavors developed at the end of his life. Rucker Publications comic books are considered a noteworthy entry in the development of Canadian comic books during the late Golden Age. The road that took him to that point had a number of twists and turns, including circus acrobat, theater performer, crime reporter, Chicago bootlegger, muckraking publisher, true crime writer, and beyond.

Much of what we now know about Rucker's life story comes from a candid and wide-ranging background interview he gave during his service in World War II, prior to being examined in 1940 for what appears to be a flare-up of injuries that he suffered during World War I. The broad outlines of this information can be corroborated and supplemented by other sources. Rucker was born in 1889, in Jacksonville, Illinois, at that time a town of around 12,000 in west-central Illinois. Census records suggest that he first spent time in Canada in 1899. His father was a traveling salesman, which may help explain why Al Rucker himself was so comfortable traveling around North America during much of the early part of his life.

Acrobat, Map Maker, Bootlegger

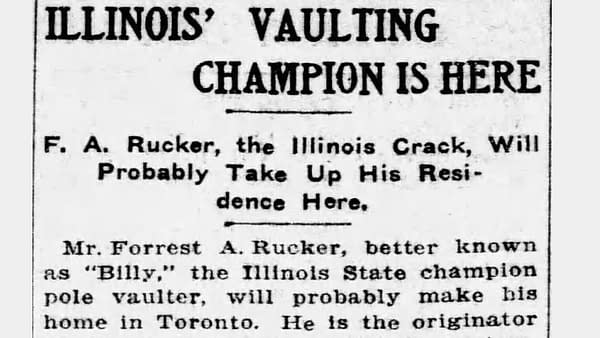

Rucker was a stand-out athlete at an early age. He appears to have been a nationally-known pole vaulter in both the U.S. and Canada in his teenage years. Of this period, Rucker recalled that "On leaving school in 1905, he began to travel with a circus, working on a tight rope and in a lion-taming set. This work was seasonal and he kept at it through the U.S.A. for three or four years. In 1909 he came to Canada with the circus and travelled back and forth to the U.S.A. for another four years. In 1913 he joined a stock company at the Royal Alexandra Theater in Toronto, in which he played juvenile roles."

In 1914, Rucker was back in school, taking evening classes at the Department of Architecture, Machine Drawing and Design of the Toronto Technical School. This appears to have been a precursor to Toronto's Central Technical School. Rucker seemed to particularly excel at scenic painting at the school, but he made significant use of the range of skills he learned there, and would refer to himself as an artist on official documents for the rest of his life. He enlisted with the R.F.C. in 1916 and according to material put together by the Toronto Star, "made and painted maps for ground school and bombing maps for Royal Flying Corps and R.A.F."

Prohibition went into effect in the U.S. in 1920, and at this point, Rucker may have made use of the knowledge gained from extensive travels between Illinois and Canada in his earlier years. By his own account, "He went to Chicago and began bootlegging. This proved both successful and lucrative, and in two years' time he had made $50,000.00. He stopped this type of work when it became 'too hot' for him." His subsequent time in Chicago proved to be the beginning of another chapter in Rucker's life. He used his knowledge of the city's underworld to become a newspaper reporter in Chicago for a year, likely around 1922-1923. While he returned to traveling theater work and used his map-making skills for the Canadian National Railway for much of the mid-1920s, his time as a newspaper reporter would eventually have a formative impact on his career.

Hush and Birth of the Week-Ender

According to Susan E. Houston's paper "A little steam, a little sizzle and a little sleaze": English-Language Tabloids in the Interwar Period, which chronicles the development of tabloid-style newspapers in Canada, Bob Edwards' Calgary Eye Opener and J.R. Rogers' Jack Canuck were among the pioneers of this category in Canada. Of course, the Calgary Eye Opener is fairly well-known to comics historians for the later 1926-1939 version published in Minnesota, initially by Harvey Fawcett, brother of Fawcett Publications empire founder Wilford Fawcett, and later published by Wilford's ex-wife, Annette Fisher Fawcett. Bearing little editorial or physical resemblance to the original, the Minnesota Calgary Eye Opener used the style and format of Wilford Fawcett's Captain Billy's Whiz Bang, and also contained often risque early work by legendary Disney Duck artist Carl Barks.

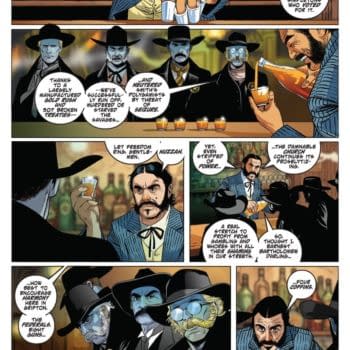

But this is not the only element of comic book history that has its roots in the world of Canadian tabloids. By sometime in the late 1920s or early 1930s, Al Rucker found himself working as a police court reporter for the Toronto tabloid Hush. This appears to have been a logical extension of his activities in Chicago, as according to one Toronto investigation, while working at Hush, "He came into contact with most of the underworld here…"

In a move that would later inspire the name of his best-known comic book series, Rucker launched his own tabloid in Toronto, the Week-Ender, in 1934. According to Houston, the opportunity to do this was created by a split between Hush publisher Strathearn Boyd Thomson and his printer Hanmer Burt Lloyd. Lloyd subsequently supported Hush rivals including the Week-Ender and Flash.

Threats to Stop the Presses

From the outset, Rucker was not afraid to ruffle feathers with the Week-Ender. Shortly after launch, he received a letter threatening him with kidnapping and murder, and stating he would be held for $200,000 ransom. The letter was connected with similar threats sent to several notable figures, including the Attorney General of Ontario and the prosecutor of a criminal case against a blackmail ring that had been operating in Ontario at that time. The letter sent to Rucker was a warning about the spotlight the Week-Ender was bringing to the case "to stop us from kidnapping or blackmailing. Kidnapping is our racket. We will wait our time when we get you we will abduct you for ransom of $200,000, your family failing to come across with ransom, we will kill you in the coldest blood. We know of a nice place to dump your lousy hide. Try to doublecross us, we will blow your brains out. We know no mercy to our victims."

While Rucker presumed the letter writer was a crank, he took it seriously enough to turn it over to the police. Investigators ultimately found that the perpetrator was a 30-year-old restaurant counterman named Michael Jordan, who was unconnected to the blackmailers and explained in court that he had just done it as a hoax. He was no harmless crank however, as the investigation revealed that Jordan also sent candies dipped in iodine to Rucker, the prosecutor, and the children of former Toronto mayor William James Stewart, in an apparent poisoning attempt. Jordan was sentenced to four years in prison over this matter.

In 1940, he would explain of his Week-Ender days, "This particular paper was a tabloid and specialized in civic scandal and sports. He earned $7,000 to $8,000 a year at this. He left management of the paper with someone else on his enlistment, but its circulation dropped and it went out of circulation approximately a month ago."

But Rucker's absence from the Week-Ender offices was not the only challenge the tabloid faced in 1939-1940. Weeks after Rucker's enlistment in the Royal Canadian Army Service Corps, Ontario Attorney-General Gordon Conant announced in early November 1939 that he had "declared war on filthy publications" in Ontario, and fired the first salvo in this war by ordering the arrest of Hush editor Richard Sair and his assistant Robert Knowles Jr on charges of publishing obscene or immoral literature, while also directing "every police division" to seize copies of the current edition of Hush from newsstands. At issue was a front-page feature article about German atrocities, titled "Love Corpses."

Conant then announced the formation of a department within the Attorney General's office to check all periodicals appearing on Ontario's newsstands. "Where there is, in our opinion, any transgression of the law, the most vigorous prosecution will be launched," he said in a statement to newspapers. "We spend millions trying to improve the educational and moral standards of our people and there is no reason for allowing them to be impaired or wasted by permitting filthy publications to be circulated. We have enough troubles now fighting a war without having the morals of our people and particularly our children contaminated with obscene or immoral literature."

Two days after taking action over the current issue of Hush, Conant made filings with the Supreme Court of Ontario asking for injunctions to stop the printing and publication of five Toronto tabloids: the Week-Ender, Hush, the National Tattler, Flash, and Scoop. According to coverage of this announcement, the law being applied allowed the Attorney-General to bring an action before the Supreme Court to restrain the publication of any newspaper or periodical which continuously publishes obscene or immoral material (this is a reference to the Judicature Act). Conant told papers he was going to take this as far as possible: "We will go as far as the courts and the law will allow. I have made up my mind that the distribution of this filthy literature throughout the province must stop."

The tenor of Conant's public statements suggests that if his move to file injunctions via the Judicature Act had failed, he may have been willing to explore the use of the censorship regulations of the War Measures Act, which had been re-invoked on September 1, 1939, giving the Canadian government broad powers to prevent the circulation of a wide range of prohibited matter. Two newspapers had already been prohibited from publishing under the authority of the WMA by that November. Faced with the prospect of a tense legal battle for their existence just as the country had assumed a war footing, the tabloid publishers chose to attempt a compromise. One week later, Hush, National Tattler, Week-Ender and Flash agreed to "reform their editorial matter in the future" and avoid printing matter that was obscene, immoral, or in any way injurious to public morals. Supreme Court of Ontario Chief Justice Hugh Rose adjourned the proceedings but warned the publishers that the hearing could be reopened immediately if they didn't make changes. Between Rucker's absence, a judicial mandate to stop pushing boundaries, and various other wartime difficulties, the Week-Ender seems to have had trouble navigating those changes. The tabloid title had ceased publishing by August 1940.

True Crime, Comics, and the Legacy of War

In the immediate wake of Germany's invasion of Poland, Canada declared war on Germany on September 10, 1939. Al Rucker enlisted four days later with the 1st Mechanical Transport Vehicle Reception Depot of the Royal Canadian Army Service Corps. He utilized his map-making and artistic skills again during World War II, creating maps and terrain models and also designing insignia and battle patches for R.C.A.S.C. Division HQ. Rucker attained the rank of Sergeant, and received a medical discharge in November 1942.

After returning from the service, Rucker was soon back in the publishing field, again tapping his crime reporting and tabloid experience by writing true crime stories for Lou Ruby, in titles like Super Publishing's True Police Cases (not to be confused with the Fawcett title of the same name). In 1944, Rucker published a burst of short-lived true crime titles himself, including Crimes Incorporated, Current Crimes, Horror Crime Cases, and Now It Can Be Told. Based on the contents of Rucker comic book titles like United Nations War Heroes, his comic publishing endeavors were at least in the planning stages in late 1944.

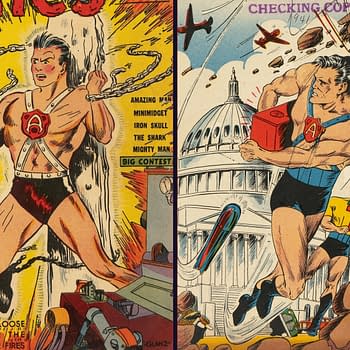

In 1945, Rucker relaunched the Week Ender (now Weekender), initially with a mix of newspaper-style photo features and comics. The series launched with the puzzling title Comic Section of Illustrated Weekender for the first two issues. The third issue then has a logo change to make Weekender the prominent part of the cover logo, and is the first issue to have a cover date, September 1945.

To put the comic book Weekender and Rucker Publications' comic book output in the proper perspective, it should be noted that Al Rucker died on August 19, 1945. He had been in the hospital since early July 1945, and for health reasons, may have found it difficult to work for some period prior. This potentially means he had little direct hands-on guidance over the Weekender past the first two "Comic Section" issues. Given Rucker's history with his legendary Toronto tabloid, it's hard not to wonder if his original intent was to revive the Week-Ender tabloid as Week Ender Illustrated News (the title masthead on the interior photo section, which had been prepared complete with a prominent 10 cent price), a photo-centric tabloid with a comic section insert. One could then speculate that with Rucker's declining health, plans were collapsed into one publication, which then evolved a bit more with his passing.

Military records indicate that Rucker had listed fellow publisher and friend Lou Ruby as his "next of kin" at the time of his death. Rucker's family situation was complicated, and he presumably felt that Ruby was well-suited to handle his business affairs. This explains the later apparent connections between Rucker Publications and Lou Ruby's Super Publishing, and given the timeline leading up to Rucker's passing, may also indicate that Lou Ruby had a hand in Rucker Publication titles as early as Weekender v1 #3 or even before.

Besides his true crime pulp endeavors at Super Publishing, Lou Ruby was also the publisher of a horse-racing monthly paper called the Thoroughbred. This may have been part of how he and Rucker connected, as Rucker owned a farm he called "Lazy Acres" on which he kept four horses. Lou Ruby also owned a horse farm. Of course, both Lou Ruby and Rucker became involved in true crime magazine publishing. Lou's brother Morris Ruby had been the publisher of Toronto tabloid National Tattler (and a companion tabloid the Tattler Review), and the Canadian version of Broadway Brevities, among many other publications. Like Al Rucker's the Week-Ender, the National Tattler ended in 1940 soon after having been among the five tabloids targeted by Ontario Attorney-General Gordon Conant in November 1939.

As noted by Will Straw in Traffic in Scandal: The Strange Case of Broadway Brevities, in 1940, Morris Ruby founded Duchess Printing and Publishing, which used imprints that included Superior Publishing. Superior is a name well-known to Canadian comic book historians and collectors. It appears that the Ruby brothers used their various companies to work together in sometimes indeterminant ways, and such is the case in comics for Lou Ruby's Super Publishing and Morris Ruby's Superior, as can perhaps be most clearly seen in the case of the usage of material from Harry A. Chesler. We also know that Lou Ruby briefly became president of Superior in 1947, ahead of Morris Ruby's eventual exit from the business by 1949. When combined with Lou Ruby's possible early involvement in much of the Rucker Publications comic book line, these connections serve to clarify the usage of Chesler output among these three publishers in Canada, among other matters.

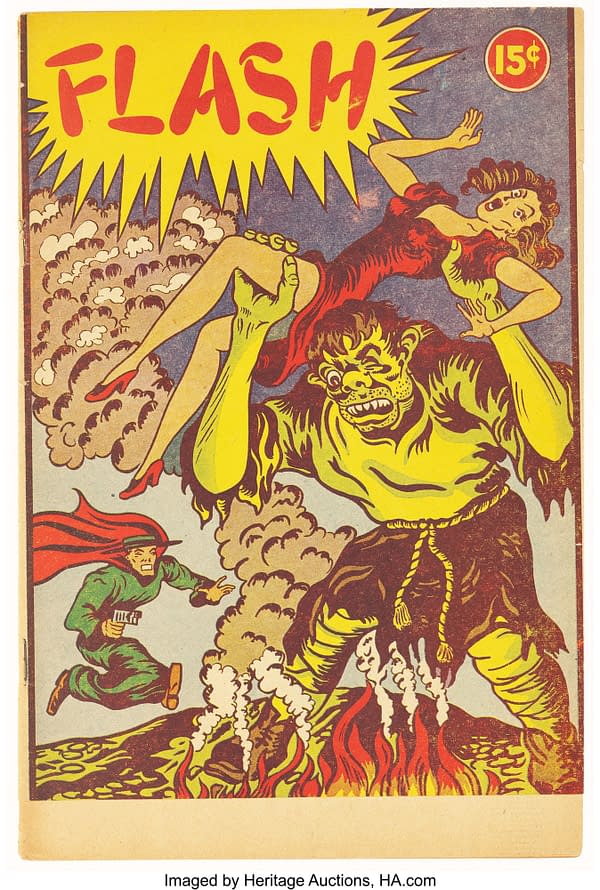

Lou Ruby acquired the Toronto tabloid Flash in 1947 and quickly made it the centerpiece of his public identity. He named his private stable of racehorses Flash Farms. This gives us all the elements needed to explain the circumstances of the 1948 Canadian one-shot comic Flash. Lou Ruby borrowed the Rucker example of naming the comic after his tabloid; it also uses Rucker Publications interiors with a Chesler-originated Paul Gattuso cover (first seen on Superior's Red Seal Comics #19) and was published by some combination of Lou Ruby and/or Superior. We'll discuss the Ruby brothers and their ventures in comics publishing in upcoming posts.