Posted in: Comics, Vintage Paper | Tagged: pulps, spicy history stories

Erman J. Ridgway: From Legendary College Football Team to Pulp Pioneer

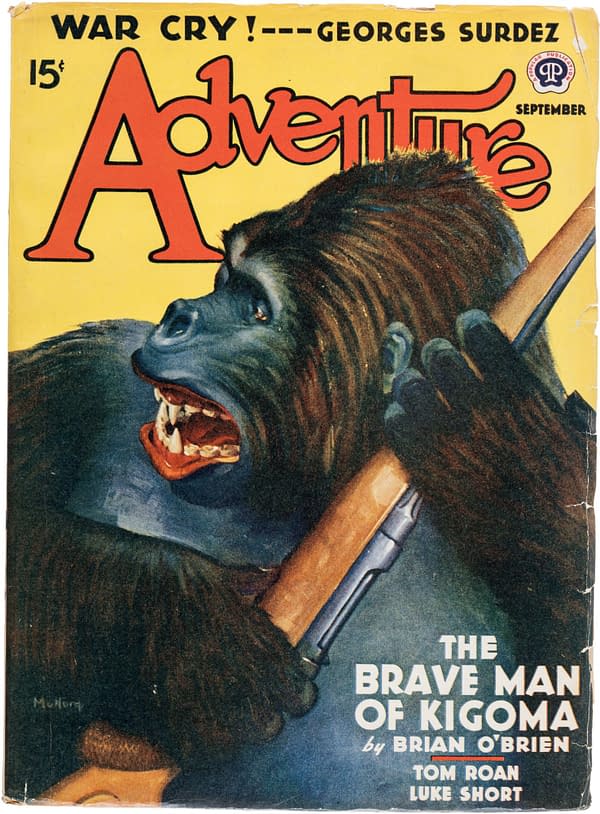

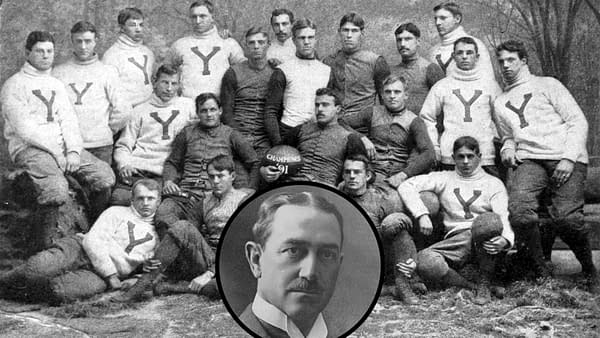

Spicy History Stories #3: Later the publisher of the iconic pulp title Adventure, Erman J. Ridgway was a player on a historically dominant 1891 Yale Football team that steamrolled opponents by a total of 488-0

Trade magazine profiles of magazine and pulp publisher Erman Jesse Ridgway often remarked that he was an imposing figure and a fit, athletic man who kept himself in shape. Ridgway had been a player on the 1888 Northwestern University football team which is considered the start of their football program. By the Fall of 1890, Ridgway had transferred to Yale during an era when the Harvard/Yale football rivalry was the biggest thing in college sports. He was good enough to have been recruited by Yale, according to some sources, and in his second season there, he was part of the 1891 Yale Bulldogs squad, considered one of the most historically dominant college football teams of all time. Yale finished 13-0 that season, outscoring their opponents 488-0, and finishing the season by beating Princeton 19-0 in front of a crowd of 40,000. This season was part of a 37-game winning streak for the Bulldogs which would not end until November 1893.

Ridgway graduated from Yale in 1892, and went to work for foundational pulp publishing figure Frank A. Munsey in 1894. Working his way up the ranks for Munsey, in 1897, he was put in charge of Munsey's New London operations, which put out Munsey's Magazine at that time. Ridgway had become a VP at Munsey by 1902 and was named a director of the firm when the Frank A. Munsey Company incorporated that year.

Welcome to Spicy History Stories #3, the third installment of a weekly column about pulp magazine history that we're launching to coincide with the debut of Heritage Auction's weekly pulp magazine auctions. Unlike other auction-centric posts we've done here, this column is not necessarily designed to be closely tied to any particular items up for auction. Mostly, it's this: if you enjoy the nerdy details of comic book history, you're going to love the astounding (and yes, sometimes weird) history of the people and companies that made the pulps.

A Media Empire Beyond Fashion

But Ridgway would soon be a publisher in his own right. He was approached by George W. Wilder and James Adams Thayer about an opportunity to acquire John Wanamaker's Everybody's Magazine for $100,000. Thayer had come up in the publishing business via type foundries, had a good eye for what modern typefaces and design could achieve, and was by this time considered one of the best advertising salesmen in the magazine industry. Wilder was the son of Jones Warren Wilder, who had become a partner with inventor Ebenezer Butterick in 1867 in Butterick Publishing Company to develop and publish sewing patterns for clothing. By the 1880s, Butterick Publishing Company would have a small group of magazines that served to promote the pattern business and discuss fashion in general, the best known of which was The Delineator. Wilder's son, George W. Wilder, had ambitions for widening Butterick Publishing's scope of influence. George W. Wilder began taking an active role in the company around 1891, and became president of Butterick in 1899, hiring Thayer as The Delineator's advertising manager. He also began to guide The Delineator into coverage of social and political reform under editor Charles Dwyer.

The Ridgway-Thayer Company was formed to acquire Everybody's Magazine in 1903 for similar purposes. Under Wanamaker's stewardship, the magazine focused on political, business, and social reform, but new management would put that into overdrive. Ridgway, Wilder, and Thayer were a compatible team, with Wilder funding the Everybody's Magazine acquisition and operations, Thayer providing guidance on design aesthetics and driving ad sales, and Ridgway spearheading the magazine's new editorial direction. Everybody's Magazine was soon an enormous success and in the process became one of the most influential muckrakers of its era, while publishing work from a huge list of notable authors of the era including Upton Sinclair, Jack London, Talbot Mundy, O. Henry, A.A. Milne and others.

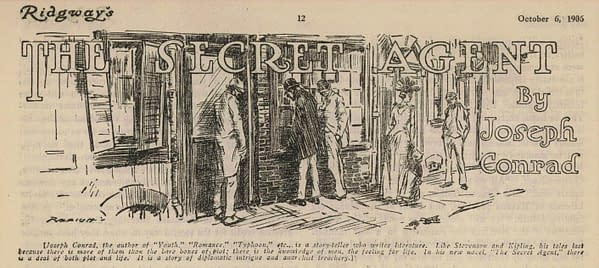

The Militant Weekly Detour

Ridgway's next endeavor would be a failure that would haunt him for the rest of his career, however. Ridgway's magazine, whose full title was Ridgway's, A Militant Weekly for God and Country, had a mission statement equal to its name. As one observer put it, the publication took a rather belligerent tone in its own introduction, which read in part: "We are only moderately terrified by that thunderborn anathema, "muckraker," and we shall use the teethed implement where there is a need and hope of abolishing muck. We shall spell in fear of the schoolmaster's rod, not of the big stick."

According to Thayer's autobiography Astir, A Publisher's Life Story, Ridgway's had been put into development by Ridgway and Wilder while Thayer was traveling the western U.S. on business, and upon his return, Thayer was dismayed by the timing and development of the new magazine. The strategy of Ridgway's included 14 localized versions to be created and released in major cities across America. Thayer felt this launch was coming too soon in the process of getting Everybody's Magazine ramped up. Likely also dismayed about Wilder siding with Ridgway against him for the first time in the partnership, he split with Ridgway and Wilder amicably.

But Thayer was right. Reaction to almost every aspect of the title's execution was terrible. Ridgway's became an expensive failure, lasting only from October 1906 to January 1907. What's more, mounting financial issues forced the now Thayer-less Ridgway Publishing Company to first issue bonds which it promoted to its magazine readership, and then also sell stock in Ridgway Publishing Company itself to its readers. While such moves had come into practice in some quarters of the magazine publishing business during this period, they could be enormously controversial.

The Path to Adventure

While Butterick Publishing Company owner George W. Wilder had been the financial backer of Ridgway Publishing since its 1903 inception, in late 1909, the Butterick company itself merged with Ridgeway Publishing via a 3-for-1 stock swap of $3 million of Butterick stock for $847,000 of Ridgway stock. Wilder was a noted stock speculator of his era, and he had effectively transformed Butterick into a holding company of other magazine publishers and publicly-traded stock by this time. And now, Erman J. Ridgway was in editorial control of the publishing empire.

The development of the legendary and influential pulp title Adventure by Ridgway the next year is something of a historical mystery. If any of the principles behind it ever discussed the matter at length, that has not been uncovered. Of course, Ridgway was now part of a public company in Butterick whose primary stockholder was using its stock to fuel acquisitions, and as such the company was highly incentivized to demonstrate expanding circulation as well.

Adventure debuted in early October with an advertising push timed to announce its appearance on newsstands, and notices from the publishing and writer's market trades around the same time. The Writer does contain a brief quote about intention from Ridgway that says, "We reasoned that a magazine edited for the universal hunger of human nature for adventure ought to have a wide appreciation and appeal, and we decided to publish such a magazine."

Then there's the matter of founding editor Trumbull White's lack of credit in the magazine itself, about which historian Richard Bleiler speculates: "Adventure was a new magazine with an uncertain future, and White may not have wanted to be associated with a potential failure. On the other hand, White may have been told to remain unobtrusive by the officials of the Ridgway Publishing Company."

The notion that Ridgway didn't want White on the masthead seems unlikely. As the founding editor of Red Book along with extensive additional editorial experience in exactly this area, White had the ideal background to help launch Adventure. It even seems possible that White was brought in by Ridgway that summer (initially as associate editor on Everybody's) for just this reason. The situation would make more sense from Trumbull's perspective, given that Ridgway's last launch with Ridgway's, A Militant Weekly for God and Country was a high-profile disaster. Even so, practically speaking, the publishing trades knew it was him within a few months, and he must have been telling friends and associates without asking them to keep quiet, as his college fraternity newsletter, of all things, had the news that he was editing Adventure within a few weeks. If Trumbull did want to keep his name out of it for fear of being associated with a disaster, then those fears were well founded because within months of launching the title, he was forced to testify in court under oath about his role in overseeing Adventure's publication of material over which Ridgway Publishing was being sued for libel. The case dragged on for nearly a decade, with Ridgway Publishing ultimately losing and paying plaintiff Louis Guenther $5000 in damages. In another early libel matter, Chicago newspapers reported that Erman J. Ridgway was run out of town on a rail to avoid a criminal libel charge due to material in the December 1911 issue of Adventure. This libel complaint was brought against Ridgway by former Department of Justice special agent George T. Scarborough.

The Guenther v Ridgway case does provide us with some historical insight into the beginnings of Adventure, however. Trumbull testified that his last day as editor of Adventure was June 17, 1911, a date somewhat earlier than history has generally believed. Arthur S. Hoffman took over managing duties thereafter. Notably, we also know that Hoffman was assisting Trumbull from the beginning, as Hoffman later recalled, "I remember how it was suddenly decided to start it a month earlier than had been intended and how, in order to get that first number shaped up in a month's less than is normally needed, Trumbull White and I practically went to live at the printer's so as to save time in transmission. It was a case of nights, days, and Sundays, and pretty much all of each."

This puts the production of the debut issue of Adventure at a time of editorial turmoil at Butterick. The Delineator editor-in-chief, Theodore Dreiser, would be forced out of Butterick in October 1910 after assistant editor Anne Ericsson Cudlipp reported Dreiser's infatuation with her 18-year-old daughter to Ridgway. This departure would put more pressure on Trumbull in his associate editor role on Everybody's as John O'Hara Cosgrave shifted to The Delineator. The timing may suggest getting Adventure to press before Dreiser's departure and helping Hoffman get the title started, and Trumbull then opting to return to Everybody's after Adventure's title launch, as it was a safer and more prestigious role. In this scenario, perhaps he went uncredited in Adventure as he intended to spend very little time on the title from the start. Also perhaps speaking to the rushed nature of launching the series is the copyright registration of the debut issue giving the full title as Adventure, A Magazine Just for Adventure Stories, which seems to appear nowhere else.

Erman J. Ridgway retired from his role as editor-in-chief of the Butterick magazines in 1916, in the face of generally declining circulation complicated by Butterick's failure to pay a dividend to stockholders the prior year. He briefly went into business with Frank A. Munsey again around 1922 as co-publisher of the New York Sun and New York Telegram. Ridgway died in 1943 at the age of 76. On April 3, 1934, Butterick sold Adventure to Popular Publications.