Posted in: Comics | Tagged: Comics, entertainment

A Fourth-World Texan Tall-Tale With All The Humanity You've Been Looking For – Talking God Country With Donny Cates

By Hannah Means-Shannon

God Country, the new Image series from Donny Cates, Geoff Shaw, Jason Wordie, and John J. Hill arriving on January 11th, feels like something both new and very old, something that's been brewing a long time over the wide lands of West Texas where it's set. It brings together the key features of Westerns, of hero myths, and of cosmic traditions from the Silver Age of comics, but none of these compelling elements are at the center of the story.

At the center is one family who are not particularly brave, wise, or deserving, any more than the rest of us, but they are facing as best they can a family tragedy: the loss of one man's life and a sense of connection to their past as Emmett Quinlan slips further into dementia. What follows is a folk tale, or a tall tale as they used to be called, of epic proportions, featuring an enchanted sword and an otherworldly fight.

This tremendously human drama features stellar artwork that emphasizes just how powerful texture and atmosphere can be in a comic story. When the comic hands down this generational story to you, you'll feel indoctrinated into the unusual realities of God Country.

Series writer Donny Cates (Buzzkill, The Paybacks, Star Trek, Interceptor) joins us today to talk about telling tall tales about human beings.

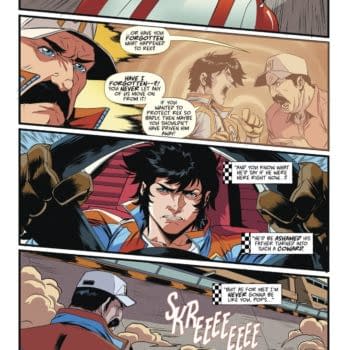

Hannah Means-Shannon: I've now read the first three issues of God Country, but I'm going to be careful not to be spoilery. I think it's fair game to talk about the central characters—a West Texas family, the Quinlans, with an aging father, Emmett, suffering from Alzheimer's. Their situation becomes swept up in a massive, just about cosmic, plot.

It seems to me that there could have been a danger of the family's role getting lost on such a big canvas. That their problems might seem little, even forgettable. But having read three issues, I'm very impressed that without a lot of wallowing in emotion, the emotion behind losing your memory or being a burden to loved ones still feels important. The comic seems to say: Just because something is common doesn't mean it's trivial. How do you strike a balance between the big picture and the small picture in a story like this? Were you ever worried you might tip things too far one way or the other?

Donny Cates: That was never a worry, no. Well, not really. To me, the big and the small of this book are one and the same. Everything in the story flows out this one line of thought, the central conflict, which is, "a small family dealing with things beyond their control. Things that cannot be ignored, only stared down and fought."

In the beginning, the thing beyond their control is Emmett and his illness. His fading away into something they cannot contain, or reason with. As the story moves ahead and grows larger and its scope increases, we were careful to never stray away from that core. The threats grow larger, but the problem remains the same. All the big cosmic trappings are just metaphorical extensions of that same idea.

HMS: Can something be both majestic and campy? I ask that in all honesty. And it's a question prompted by Valofax. The high-flying, over-the-top mythic language this celestial sword uses is familiar from a thousand myths, folk tales, and sagas. It's piled on in a way that seems camp at first, but when he starts to mention individuals and his relationship to them, it's like individual heroism is singled out as situated within this big cliché we need to shake off. You've somehow made Valofax comedic and dead-serious.

DC: Yes! I think, yes. A lot of that campiness is absolutely there on purpose. A lot of it is derived from a Kirby Fourth-World Larger-than-life type of…'grand speechifying', I suppose is a way of saying it. I imagine the gods have two ways of speaking. One is a kind of operatic booming tone they use in a more formal way, a way they speak when addressing mortals or inferiors…and then another way of speaking that they reserve for each other, a more casual…but still relatively grand pattern.

Walt Simonson's Thor and Neil Gaiman's Sandman were both big influences on the language of the book, but so were Cormac McCarthy and Larry McMurtry. One of the biggest thrills I get from writing this story is matching that kind of grandiosity of the god's speech with the southern drawl and very plain, matter-of-fact way of speaking that our resident Texans have in the book. Those two things have bumped against each other to vibrate in a way I really enjoy.

HMS: Tradition seems like the big word in the context of this series. We have the multi-generational legacy in a West-Texas family, the house built by hand, the landscape. Then we have Valofax and gods who want things done a certain way. And the comic itself is somewhat traditional. This is a narrated folk-tale of strange happenings, and the alien-god interaction feels Kirby-esque or early Thor-like. Is there something to be said for reframing traditional elements to make a fresh connection with readers?

DC: Absolutely. I've always described the book as a "Fourth-World Texan Tall-Tale" And the unseen narrator was a conscious effort on my part to make this story feel big and unwieldy, and maybe exaggerated in the way tall tales like Paul Bunyan or Pecos Pete feel. But at the same time, we know that our narrator is family. Whoever they are, they're blood. So, I feel like the story is being told to you, the reader, from a place of love and reverence for the people inside of it.

It's important that the story, which, as we've talked about, can get pretty far out there, is kind of told by way of being handed down. The story is itself a part of the family, so the book you are holding becomes an heirloom. And by virtue of you holding it, you are a part of that family. Because you now own something that belongs only to them, and you now have the same power as the storyteller. You can hand it down as well. You can tell this story to someone else. It lives with you. It belongs to you.

HMS: It's not that often, however, that you seen an old guy wielding a giant sword, or any other weapon for that matter, in a comic. And yet there are lots of legends and stories in many cultures that do focus on the end days of heroes or famous rulers. There's the second half of Beowulf, when he's getting on in years and yet fights a dragon, for example. Comics are often accused of ageism, actually. Does it feel good to let rip with a story of a tough as nails older dude standing tall?

DC: Well yes, and I'll tell you why. When you tell a hero's journey, the third act (especially in antiquity) is a time reserved for the acquiring of knowledge. Old men in ancient stories are often described as being wise and intelligent with their years. Here we have that idea of a third act that has been stolen. Alzheimer's has taken away that graceful, wise third act for Emmett and he rages against that theft (in every form it takes) for the entire series. So we begin our story with a third act, with all that comes with it.

In fact, aging protagonists are really prevalent in a variety of genres, and comic has its fair share (The Dark Knight Returns, Old Man Logan) as do the ancient stories (the Beowulf and Hrunting/Emmett and Valofax comparison is more on the nose than you think) but the biggest culprit of this trope comes in a genre that is obviously very important to the series, and that is the American Western. Westerns have long been a haven for the old guys to kick some ass. True Grit, High Noon, The Searchers, Unforgiven, Lonesome Dove…the list goes on and on. The Western genre is FULL of stories of One Last ride and Riding Into Sunsets.

Of men who are the last of their kind (Lonesome Dove for instance) or who have grown too old in a world they don't recognize and don't belong in (No Country for Old Men is a good example of this, if not an obvious one), or old men with dangerous pasts trying desperately in their third act to atone for them.

So anyway, obviously these are things that matter to me, and to the story. So this is all a very long and boring way of saying that, for a story that has one foot in the ancient, with its gods and swords, and one in the American Southwest, it makes all the sense in the world to me that our protagonist has more than a few miles on him. And yeah, it's fun to watch an old dude kick ass with a giant sword, too.

HMS: Tell me about the ways in which Geoff Shaw's art is unique to this book—I see some real shifts as he's adapted his style to this story. Do you have any favorite panels or scenes you can talk about?

DC: Geoff is a master. I don't know how else to say it really, but he can sell an emotion like no other artist I know. And for this kind of story, the emotion comes first and foremost. He's also just insanely malleable and adaptable. His style changes so hard from book to book depending on the tone, but still remains unmistakably GEOFF SHAW. His work on The Paybacks is different from Buzzkill, for instance. Paybacks was just an out and out absurd action/comedy, so he was in service to the jokes and the outlandish there, so he really went wild with his cartooning and made everything very clean and slick.

If you look at Buzzkill, his art becomes scratchy…raw. That's because that book was four issues of an open wound. It had to look rough, and irritated. Closed off and claustrophobic. Intense.

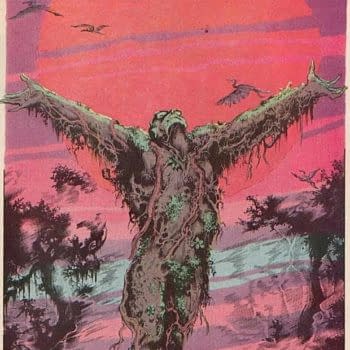

And then he comes to God Country and he just explodes in these incredible widescreen panels of lush landscape and endless horizons. Because he wanted it to feel BIG and MYTHIC. And it does. Does it ever.

I'm often asked "What does Geoff Shaw add to the story?" and it's become a strange question to me. He doesn't add to the story…There is no story without Geoff Shaw. He'd be here talking to you all just as passionately as I am if he wasn't busy drawing the damn thing while I'm here yammering on and on. Geoff is a great friend and my absolute favorite person to collaborate with. He's a treasure of a storyteller and I'm lucky as hell to be by his side.

And if I may brag on my team for just a second…getting Jason Wordie to come in and paint this thing the way he has…god, I gotta tell you it never looked this pretty in my dreams. Every time I see his pages come in, it's a wonderfully surreal pleasure. He has this way of coloring the book that feels…old. And bright and strange and haunting. Like we're seeing it all through someone else's memory of it all. I don't know how else to say it. It's wonderful.

And then to have John J. Hill to come on for letters and design. Anyone who's seen that insane logo of ours can thank John for that. And he's added so much storytelling through his lettering, too. The way the gods speak, and the way Valofax speaks…it's all perfect. John's work is another great example of someone coming aboard a project and knowing EXACTLY what it called for. He got the BIG memo and ran with it hard.

And then Gerardo Zaffino with these variant covers! God what can I say, right? How blessed can one guy get in the art department? Gerardo has this variant for issue four that…ah! I can't say anything about it because it's a spoiler…but it's hands down one of the most beautiful and violent images I've ever seen.

HMS: Thanks for calling out all the art and design elements, along with the members of the team, Donny. That's quite a line-up.

Does the size, scope, and visible distance of a place like Texas suggest a kind of massive scale to you in a way that fits gods? I mean, the title is "God Country". Is this naturally a place that gives vastness to the imagination?

DC: Yeah totally, and to follow up on what I was just saying about Geoff, he and I actually made a little research trip out to West Texas and he was just studying everything…He brought a camera and must have taken thousands of pictures of rocks and grass and alleyways and hills and sunsets. He wanted to try and find a way to grasp the bigness of it all.

Geoff summed it up perfectly, I think, one day when we were out hiking up this big ass hill. We got to the top and he looked out over the endless hills and the vastness of West Texas and he said "If you looked out there and saw twenty-foot-tall gods fighting, you'd be shocked…but it wouldn't seem that out of place."

HMS: What can we expect, coming up in God Country? Any hints?

DC: It's going to get a lot worse before it gets better.

…

Wait, no…for the Quinlan family, I mean. The family in the book.

I'm not saying the book gets bad and then ge-oh whatever, you know what I mean. Please go pre-order God Country, and give us a shout at GodCountryComic@Gmail.com!!

God Country #1 is available for pre-order with the following code: NOV160545 and reaches FOC on December 19th. Issue #1 arrives in shops January 11th.