Posted in: Comics | Tagged: Comics, david hine, entertainment, Second Sight

Talking Second Sight, Dark Tones, DC And Marvel With Creator David Hine

By Olly MacNamee

Olly MacNamee: You broke into comics as an artist, and quite often as an inker early on. Was art your main interest back then, or had you wanted to write stories too?

David Hine: I always wanted to write stories. I was eight years old when I wrote my first novel and was banging them out for a while: a science fiction story, a western, an historic thriller, a mystery. I liked to draw as well and by the time I was twelve or thirteen I knew I wanted to work in comics. I concentrated on the drawing because all the people I admired most seemed to be artists. I tried to emulate Kirby, Ditko, Steranko, Adams, Wrightson, or ideally writer/artists like Will Eisner or Vaughn Bodé.

OM: It was Strange Embrace where you came into your own, both writing and illustrating the book, and then with Mambo in the pages of 2000AD. How did that then develop into you becoming a comic book writer full time?

DH: Strange Embrace was a great experience for me. It was by far the strongest thing I had created and I finally had the confidence to jump into a long-form work and to draw in what I think of as my own style. When I was drawing I was always jumping around from one style to another. Mambo, for instance, was me trying to be commercial and working in the style I thought would be popular for the 2000AD audience. I found the more expressionistic style that I used for Strange Embrace when I was on holiday with no photo reference to cheat with, and that style just seemed to come naturally.

The problem was that Strange Embrace didn't sell well and in the pre-internet days I had no feedback whatever, so I assumed no one liked it. I gave up on comics and spent almost a decade doing very mediocre commercial illustration, which paid the rent but was soul destroying. It was only in 2003 that Richard Starkings contacted me to reprint Strange Embrace as a graphic novel and I finally discovered that a lot of people had really loved the thing. Once it was back in print, it was picked up by a lot of influential people, like Joe Quesada who immediately offered me work at Marvel – but only writing. No one at Marvel has ever asked me to draw. Once I started scripting Daredevil: Redemption and District X there was no looking back. The work has been coming in steadily ever since.

OM: Looking at your resume, Dave, would it be fair to say that, as a writer, you are drawn to darker characters such as Daredevil, Deathstroke and Spawn? And, if so, why are they more appealing to write about?

DH: Yeah, I definitely am drawn to the dark side. You can add The Darkness to that list too. I wrote the book for Top Cow for a couple of years. The work I'm doing with Mark Stafford is very, very bleak, although I like to think it's also quite amusing. Mark recently drew a page of The Bad, Bad Place for Meanwhile that is probably the most disturbing single page of comics I've ever had a hand in. I probably just have a sick mind, but if pressed I usually claim it's a way to confront my own anxieties about death, disease and mental illness. In real life I like to chill out with friends, walk along a beach at sunset and pet kittens but who the hell wants to read about that?

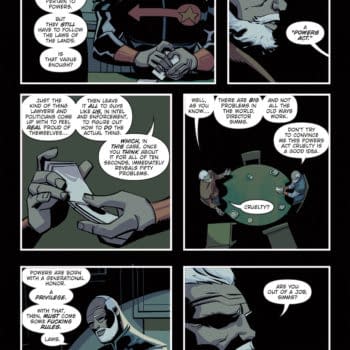

OM: Your new comic, Second Sight, from Aftershock Comics sees you embrace the darkness once again, taking on the all-too real issues of child abuse and those in powerful positions "Who are prepared to kill anyone who threatens to expose them". Do you believe comics can act as a valid form of social commentary on such topics in ways other creative mediums can't?

DH: Any art form is valid for any kind of commentary. I never set out specifically to make any kind of political or social comment but my opinions always creep in there somewhere, so I ended up making Peter Parker, Aunt May and Uncle Ben overtly communist in Spider-Man Noir for instance and of course there was Nightrunner the 'Muslim Batman' at DC. It does look like I'm being provocative but honestly these just seem like the logical choices when I write them.

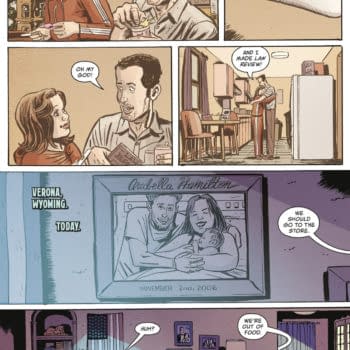

The plot for Second Sight was originally written in the 1990s. I had been hearing stories about a paedophile ring that included prominent politicians and entertainers from all kinds of sources. I'm not going to repeat any names as this is all hearsay and unsubstantiated, but one name that was coming up all the time was Jimmy Savile and look how that turned out. Again, I wasn't intending to take on the issue of celebrity child abusers in any specific way. This is all about confronting and dealing with the essence of evil.

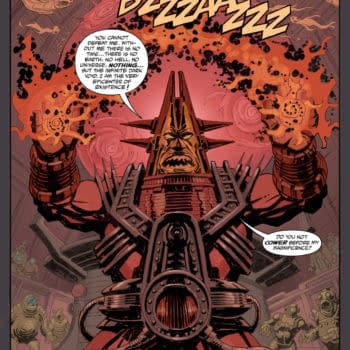

Ray and Toni Pilgrim are hunting the most repulsive elements in society and the ring of abusers known as The Wednesday Club is essentially a metaphor for the immorality that permeates the power structure in Western society. There's a masked character called The Reaper who is the personification of evil, but the faceless members of The Wednesday Club are the real bad guys, the people who always get away with it, and who always remain in power.

OM: Your characters, such as Ray Pilgrim and his dysfunctional friends and family, certainly seem to live in a more real world than, say, Spider-Man. Do creator owned characters mean you can be truer to the storyteller you want to be?

DH: It's always easier to remain true to yourself if you own the characters. That goes without saying, but you can do a lot with the corporate characters too. Daredevil: Redemption was inspired by the real-life case of the West Memphis Three and was very realistic. The legal side of it was particularly well researched. The same with Spider-Man Noir. Although there are fantasy elements, the political and social background was heavily researched and apart from the magic spiders and visions of Anansi, it could almost be social realism. What I have more problems with when I'm writing mainstream comics is to compromise on the story in order to fit with whatever editorial overview is currently in place. At worst that means struggling with a crossover event with a dozen different writers all working to conflicting ends. Individual story lines often suffer in those circumstances.

OM: What are the advantages of playing in someone else's sandpit when you work on books for Marvel and DC?

More money and a bigger audience. That's the bottom line. When people ask what I do, it's gratifying to be able to say that I've written Batman and the X-Men and I do get a kick out of working on characters I loved when I was younger. Writing Will Eisner's The Spirit was the biggest thrill for me. I always loved the way Eisner and other writers like Jules Feiffer managed to tell such beautifully complex stories in seven pages and I really enjoyed trying to do the same thing with 20 pages. I see every project as a challenge to tell the best possible story within the parameters I'm given. When those projects are on the level of the Civil War X-Men series it puts my work in front of a lot of people and that's a great help when I need to find an audience for the independent work. Whether it's The Bulletproof Coffin or Storm Dogs or Second Sight it's easier to get attention when you have a CV that includes A-List characters.

OM: Back to Second Sight, with the first two issues already on the shelves, where will subsequent issues take us? What next for Ray Pilgrim and the gang?

DH: The territory gets bleaker, darker, more depressing. It kind of reflects the way I'm feeling about the world right now. The only gleam of light is in the human relationships, the knowledge that there are good people trying to do the right thing. There are plot twists and revelations with every issue and I've actually made one major change to the way the story goes in the last episode. It suddenly hit me that there was a really obvious choice to be made that I hadn't seen before. It's always very cool when characters take on a reality and start telling you what they should be doing. Toni is constantly looking over my shoulder, making caustic comments about my writing. I've lived with the characters for a couple of decades in one form or other and it's really weird in a positive way to have them finally take shape through the pen of Alberto Ponticelli.

OM: Looking back, for a moment, at your critically acclaimed graphic novel, The Man Who Laughs. Victor Hugo isn't the easiest of reads now is he? What drew you to this particular story to adapt?

DH: I wrote an issue of Batman and Robin set in Paris with a new version of the Joker that referred directly to the fact that the Joker was inspired by a movie poster of The Man Who Laughs, which had been filmed for Universal by Paul Leni in 1928 with Conrad Veidt in the title role. Out of curiosity I tracked down the book and when I read it, I was totally grabbed by this Grand Guignol horror story that was also an incisive attack on the system of aristocratic privilege in Britain. I loved the twists and turns of the story, the characters and the vividly visual storytelling. I found scenes playing out in my head that seemed made for the comic book page and it dawned on me that this story needed a wider audience than it was getting.

There have been several comic book adaptations, a French TV series and several films but I was pretty sure that Mark and I could come up with something unique. I avoided looking at any of the existing versions until the script was finished and it's fascinating to see where the versions overlap with ours and where they seem totally different. I concentrated on the politics of inequality as that seems particularly relevant to the way society is polarising right now. As I've said before, Gwynplaine's climactic speech to the House of Lords is as relevant today as it was when the book was written in 1869. The book is also a thriller and a love story and a whodunit with engaging and unique characters. That gives it a far wider appeal than you would expect from "The story that inspired The Joker."

OM: What next for you, Dave? Any more plans for creator-owned series such as Second Sight? Or, after The Man Who Laughs, do you have any more desires to adapt from any further literary classics?

DH: I have no plans for more adaptations. It was fun to do, but I have lots of my own stories to tell. There are a number of projects I've worked on over the past few years that were either aborted or are stalled at various stages and that's very frustrating. Now I'm looking to do more work with Mark Stafford. The big ones are The Bad, Bad Place, currently being serialised in Meanwhile from Soaring Penguin and Lip Hook, which is an ambitiously long supernatural thriller I have been known to pitch as "Wicker Man meet Apocalypse Now by way of Village Of The Damned." Then there's a new Bulletproof Coffin one-shot written and waiting on Shaky Kane's drawing table as soon as he has a gap in his schedule. I'm also working on a couple of science-fiction concepts and there will be a second volume of Storm Dogs when all the right stars are in alignment.

OM: As noted at the beginning of this interview, you started out as an artist: Do you have any intentions of taking to the drawing board again anytime soon or have you decided those days are behind you now?

DH: It takes an awful lot of persuasion to get me to draw anything these days. It was always a painful, slow and unsatisfactory process for me. Drawing doesn't come naturally to me. I made a living at it, but that was out of sheer bloody-minded determination rather than talent. The last major thing I did was an issue of Elephantmen a few years back. I can't see myself going back to drawing for a living. Writing is far more enjoyable and I get to work with artists who do the job so much better than me.

OM: Many thanks for your time!

DH: You're welcome.

David Hine will be a guest at the convention taking place on April 23rd that is part of this year's Birmingham Comics Festival in the UK.