Posted in: Comics, Vintage Paper | Tagged: captain america, Promise Collection

The Promise Collection 1941: Captain America, Super Soldiers and Spies

In histories about the Golden Age of comic books, it's invariably noted that Captain America Comics #1 was published nearly a year before America entered World War II. That March, 1941 cover-dated release hit the newsstands around December 20, 1940, according to Library of Congress copyright records, while America declared War on Japan on December 8, 1941 in the wake of the attack on Pearl Harbor, and responded in kind to Germany and Italy's subsequent declaration of war on December 11, 1941. Of course, Captain America was not the first patriotic superhero character of the modern comic book industry. The Shield debuted over a year prior to that in Pep Comics #1, and as we saw in Part 1 of this series, other characters had been getting involved in the approaching war in various ways throughout that year. And these superheroes had plenty to handle even before stepping foot on the battlefield.

A careful reading of the comic books of this period can tell one quite a lot about their moment in history. Throughout the early issues of his series which were on the newsstands in 1941 before America's entry into the war that December, Captain America fought battles against spies, saboteurs, fifth columnists, and propagandists on the home front — and as we shall see, the threats portrayed in those issues of Captain America Comics were reflective of their moment in time. Captain America Comics #1 and all the rest of the early issues of that series are among the highlights of the Promise Collection from early 1941.

Welcome to Part 2 of the Promise Collection series, which is meant to serve as liner notes of sorts for the comic books in the collection. The Promise Collection is a set of nearly 5,000 comic books, 95% of which are blisteringly high grade, that were published from 1939 to 1952 and purchased by one young comic book fan. The name of the Promise Collection was inspired by the reason that it was saved and kept in such amazing condition since that time. An avid comic book fan named Junie and his older brother Robert went to war in Korea. Robert Promised Junie that he would take care of his brother's beloved comic book collection should anything happen to him. Junie was killed during the Korean War, and Robert kept his promise. There are more details about that background in a previous post regarding this incredible collection of comic books. And over the course of a few dozen articles in this new series of posts, we will also be revealing the complete listing of the collection. You can always catch up with posts about this collection at this link, which will become a hub of sorts regarding these comic books over time.

A Force of Super-Men

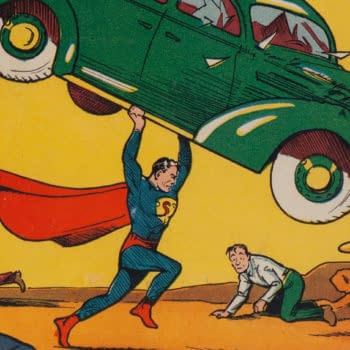

I think we have the notion that "The Superman" was a vague, Nietzschean concept barely remembered by the general public of the early 1930s — introduced into the vernacular due to Friedrich Nietzsche and George Bernard Shaw around the turn of the century, but then revived with the likes of Doc Savage and Philip Wylie's Gladiator. But the second part of that notion is untrue. The term was vaulted (it might be more accurate to say "re-introduced") into significant mainstream media attention in America directly after WWI.

As we saw in Part 1 of this series, the term "superhero" had also achieved mainstream usage in America before it was applied specifically to comic book characters, so it should come as no surprise that the notion of a "super soldier" was likewise somewhat familiar to the public by the time of World War II. Indeed, a few months before Captain America Comics #1 hit the newsstands a bit of propaganda was slipped to the Berlin office of the United Press by a "semi-official Nazi source" stating that "Young, specially-equipped super-soldiers, selected for their intelligence and athletic prowess, will lead the German attack on the British Isles if and when it occurs." This was picked up by newspapers around the country in September 1940. The notion of the super-soldier had entered the wartime media.

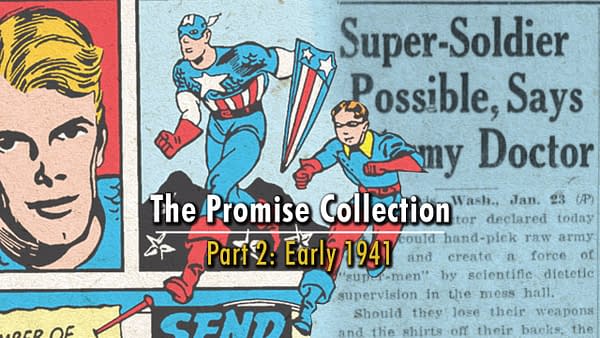

It wouldn't end there. The seeming response of the American super-soldier would be both swift and surprising from our perspective 80 years later. Captain America Comics #1 came out in late December, and with that debut issue still fresh on the newsstands, newspapers carried a statement about the real possibilities of an American super-soldier from a U.S. Army doctor:

Super-Soldier Possible, Says Army Doctor

An army doctor declared today that he could hand-pick raw army recruits and create a force of "super-men" by scientific dietetic supervision in the mess hall. Should they lose their weapons and the shirts off their backs the "tiger" in them would still make the men dangerous as a battering, bare-fisted brigade.

"If I had the opportunity to personally select 5,000 men from the 48,000 we expect to have in this area by spring, and feed them a specially prepared diet which included increased mineral and vitamin content, I would have a small army of unbeatable men within six months, asserted the colonel, who is the surgeon in charge of the entire 3rd and 41st divisions at Fort Lewis and Camp Murray.

"They would be super-men — men who would fight with rocks and their bare fists if they lost their weapons. They would be a superior type of shock troops, which seem to be so successful in modern winning armies."

"Hopped up" only through an improved diet, the troops would be as superior mentally as physically, and they would be capable of acting resourcefully alone as well as in a group.

Verbiage like "the tiger in them would still make the men dangerous as a battering, bare-fisted brigade" and "men who would fight with rocks and their bare fists if they lost their weapons" sounds like a Simon & Kirby comic book in the making, but the "hopped up" barb in this article was a clear shot at the reality of the German notion of armies of enhanced soldiers. Hitler's Blitzkrieg strategy among others was greatly aided by the widespread use of a methamphetamine called Pervitin and other drugs, and this had already become publicly known in the U.S. in 1941. According to numerous sources, "Otto Ranke, director of the Institute for General and Defense Physiology at Berlin's Academy of Military Medicine, suggested that methamphetamine compounds could improve the soldiers' performance. Introduced in the daily rations and consumed up to twice a day, the drug gave the soldiers supernatural capabilities. Fearless and cheerful, they could spend more than three days without sleeping and walk up to 60 kilometres without interruption. This allowed for the fast invasion of Poland in 1939, the Blitzkrieg through the French Ardennes in 1940, and the Balkan Campaign of 1941, fought without rest for 11 days."

Enemies of Liberty

Captain America and The Shield before him have some interesting parallels in this period before America entered the war. Both were more like government agents than soldiers for much of this early era. The program which develops the serum that turns young Steve Rogers into Captain America appears to be happening under the auspices of "J. Arthur Grover", head of the FBI (an obvious stand-in for real FBI Chief J. Edgar Hoover). The inventor of the super-soldier serum process, Professor Reinstein, ultimately declares Steve Rogers "the first of a corps of Super-Agents, whose mental and physical ability will make them a terror to spies and saboteurs." Similarly, the Shield's origin explicitly notes, "Joe Higgins, G-Man extraordinary, is the Shield. Only one living man knows the Shield's true identity and that man is the chief of the FBI — because Joe's father was killed in the famous Black Tom Explosion set off by foreign spies during the World War, he, from that time forward swore to devote his life to shielding the U.S. Government and its people from any harm…"

This mention of the Black Tom Explosion gives us a direct hook into the concerns of that day which helped inspire the creation of such comic book "Super-Agents" during the Golden Age. On July 30, 1916, two million tons of war materials bound for Britain and France had been blown up by German saboteurs in the Black Tom railroad yard on what is now part of Liberty State Park. The explosion rocked lower Manhattan and Jersey City, killing three men and a baby, and its shock waves were felt as far away as Philadelphia. Flying debris pelted the Statue of Liberty, damaging the raised arm that holds the torch of freedom. The arm and torch of the Statue of Liberty have been closed to tourists since that moment. Due to this and other provocations, Congress passed the Espionage Act the next year. Ironically, the Espionage Act was used for the first time against cartoonists, when the U.S. Post office banned the magazine The Masses from mailing an issue due to what it called anti-war cartoons. Cartoonists and staff of the magazine were later put on trial — an under-discussed moment of U.S. publishing history that had likely not been forgotten in New York City publishing circles as WWII approached.

The Black Tom Explosion and other German acts of sabotage were likewise far from forgotten by the American public of 1940 and 1941. Throughout 1940, manufacturing plant accidents frequently set off fears of sabotage. By the beginning of the next year the FBI was telling the public that it was far better prepared to deal with sabotage and espionage than it was during WWI, just as the fictional version of J. Edgar Hoover was unleashing Captain America on spies, saboteurs, and any other enemies of liberty in the pages of Captain America Comics #1. Even the Red Skull fit into the spy and saboteur mold more than anything else in this issue.

Invisible Weapons

The story "Trapped in the Nazi Stronghold" in Captain America Comics #2 begins with a speech at what seems to be a political event of some sort, "Gentlemen, the time has come when the democracies must stand together. The fate of the world depends on Britain's victory. The fate of Britain rests on the financial aid of our own Henry Baldwin." The subject of that speech was subsequently kidnapped by Fifth Columnists to prevent that crucial aid to Britain from ever happening. Captain America travels to Britain to prevent Nazi agents from sabotaging the financial aid deal and then race onto Germany to rescue financier Henry Baldwin himself.

A plot centered around wartime financial aid to another country might seem like an unusual way to go about a comic book superhero adventure, but this issue was one of the most pressing and important matters in America at just the time that Captain America Comics #2 was on the newsstands. And in fact, we can also see how it came to be so through the lens of comics. An editorial inside the front cover of All-American Comics #9 noted over a year prior that, "Now that war is here again in Europe, we hope that all of our readers will support in thought and action, our President's Neutrality Proclamations, to the end that American boys (and girls) will not again have to undergo the horrors of war!"

During this period of history, Franklin Delano Roosevelt faced a public and U.S. Congress that was strongly in favor of an isolationist policy as the rest of the world marched into war, but in his famous Four Freedoms speech for the State of the Union address on January 6, Roosevelt pointed specifically to the UK's importance to democracy around the world, and of the importance of lending America's resources to the effort. We can see echoes of FDR's language (shown below) in the conference speech that opens Captain America Comics #2 and throughout the story.

Let us say to the democracies: "We Americans are vitally concerned in your defense of freedom. We are putting forth our energies, our resources and our organizing powers to give you the strength to regain and maintain a free world. We shall send you, in ever-increasing numbers, ships, planes, tanks, guns. This is our purpose and our pledge."

With the Blitz against Britain still raging, days later FDR introduced the Lend-Lease program to Congress. Captain America Comics #2 with its plot revolving around wartime aid to Britain hit the newsstands the next month, closely reflective of such concerns and the means to address them. Notably, Stan Lee — whose first Marvel Comics credit would come the next issue in Captain America Comics #3 — may have worked on a comic book-like publication in support of the Lend-Lease program for the Signal Corps after he joined the U.S. Army the next year. The famous photo of Lee during his army tenure has a copy of a publication called Invisible Weapon sitting next to a copy of Marvel's Terry-Toons Comics #25 on his desk. This is a pamphlet that uses sequential art to explain and support the Lend-Lease program effort, and it's very much the kind of thing that Stan was likely doing in the Signal Corps at that time.

As for the spy rings and saboteurs that filled the pages of Captain America Comics in 1941, it's easy from our modern perspective to dismiss such matters as simple fodder for the comic books and other fiction of those times. The FBI was warning about the propaganda impact of espionage false alarms by mid-year. And yet… such concerns would not hit so far from home for the comics industry as one might think. For example, it later emerged that beginning in 1939, a Soviet spy in America placed an asset inside McClure Syndicate because they suspected McClure owner Richard Waldo of being a fascist agent (that Soviet spy asset, Elizabeth Bentley, would later report to her handler that she could find no evidence to support this assertion about Waldo). That company looms large over the comics history of the era and figures heavily into the publication debut of Superman. Elizabeth Bentley eventually turned herself in to the FBI, and would ultimately help trigger the "Red Scare" which would in turn influence the comic books of the later era of the Promise Collection.

But there's still a lot of ground to cover in 1941 and beyond before we get to those late 1940s and early 1950s issues in the Promise Collection. We'll continue discussing issues cover-dated 1941 in next week's installment of this series. Publishers had gotten very good at presenting the conflicts and concerns of the times in ways that readers like Junie would find compelling, and we'll see that progress with a few fascinating twists in the comics present in the Promise Collection from the rest of 1941. Images and CGC grades will be added to the listings below as they become available, and in the meantime, you can check out what's already been revealed from the collection on the Heritage Auction site.

| Title | # | CGC Grade / Auction Links | Price Realized |

|---|---|---|---|

| Batman (1940) | 4 | ||

| Batman (1940) | 5 | ||

| Captain America Comics | 1 | CGC 3.5 | |

| Captain America Comics | 2 | ||

| Captain America Comics | 3 | ||

| Captain Marvel Adventures | 1 | ||

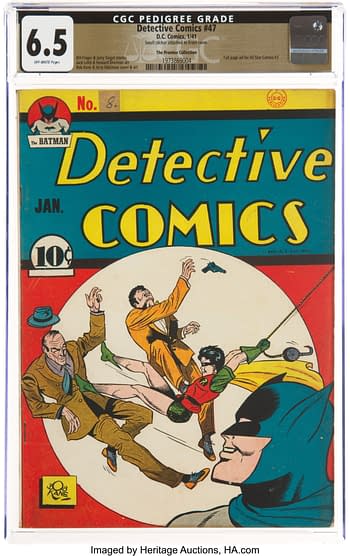

| Detective Comics | 47 | Detective Comics #47 CGC FN+ 6.5 Off-white pages | |

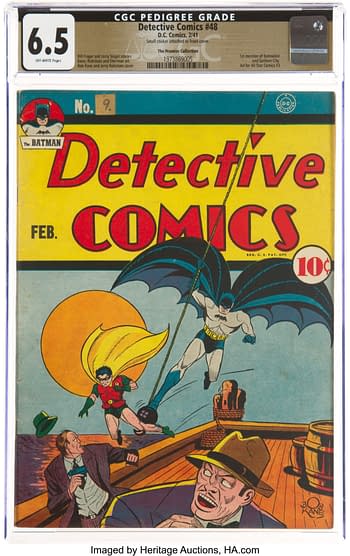

| Detective Comics | 48 | Detective Comics #48 CGC FN+ 6.5 Off-white pages | |

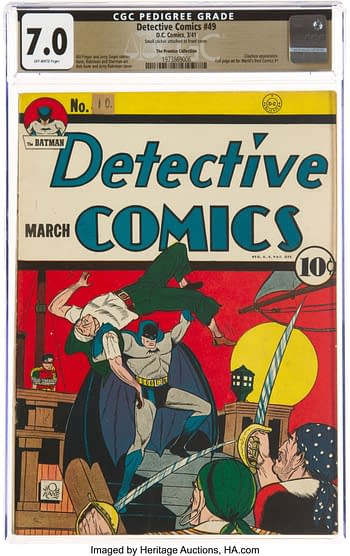

| Detective Comics | 49 | Detective Comics #49 CGC FN/VF 7.0 Off-white pages | |

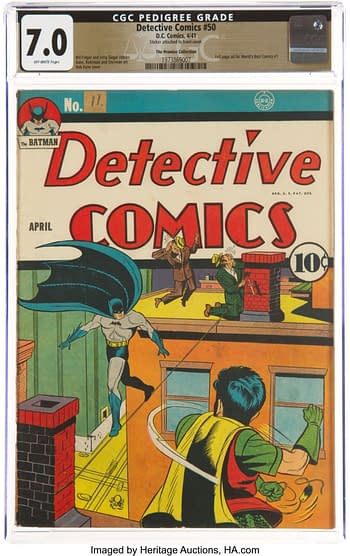

| Detective Comics | 50 | Detective Comics #50 CGC FN/VF 7.0 Off-white pages | |

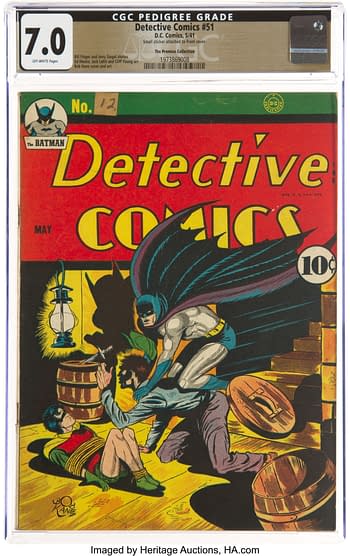

| Detective Comics | 51 | Detective Comics #51 CGC FN/VF 7.0 Off-white pages | |

| Whiz Comics | 14 | ||

| Whiz Comics | 15 | ||

| Whiz Comics | 16 | ||

| Whiz Comics | 17 | ||

| World's Best Comics | 1 |

- Detective Comics #47 The Promise Collection Pedigree (DC, 1941) CGC FN+ 6.5 Off-white pages

- Detective Comics #48 The Promise Collection Pedigree (DC, 1941) CGC FN+ 6.5 Off-white pages

- Detective Comics #49 The Promise Collection Pedigree (DC, 1941) CGC FN/VF 7.0 Off-white pages

- Detective Comics #50 The Promise Collection Pedigree (DC, 1941) CGC FN/VF 7.0 Off-white pages

- Detective Comics #51 The Promise Collection Pedigree (DC, 1941) CGC FN/VF 7.0 Off-white pages