Posted in: TV | Tagged: b5, babylon 5, harlan ellison, j. michael straczynski, jms, Repent! Harlequin Said The Tick Tock Man

J. Michael Straczynski Pens Heartfelt Letter About his Friend, Harlan Ellison

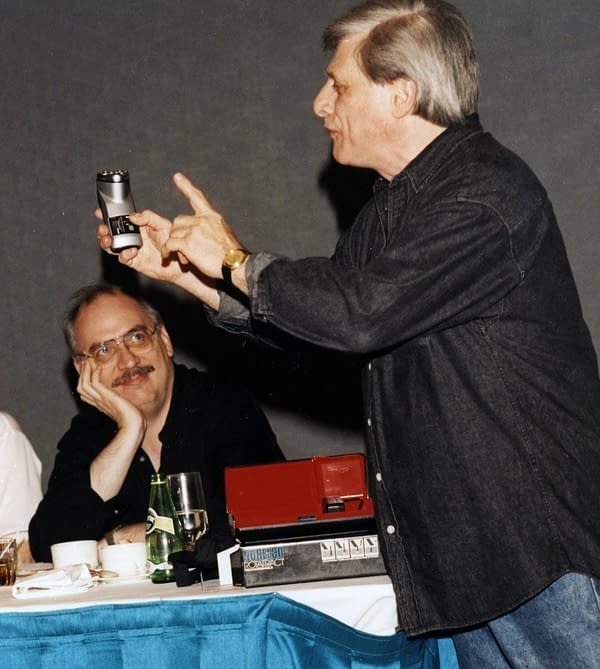

Yesterday the science fiction universe said goodbye to influential and one of kind author Harlan Ellison. Author and friend to Ellison J. Michael Straczynski took to his facebook page to write a letter, talking about where he came from and how important Harlan's friendship was to him.

The pair worked together a few times, Ellison wrote two episodes of JMS's Babylon 5 space-centric tv series, as well as JMS adapting for film one of Ellison's works, "Repent, Harlequin! Said The Tick Tock Man" .

You can read JMS's letter here, or scroll down:

I come from a background of absolute poverty. As a kid I lived in the Projects in Newark, in the roughest parts of Paterson and Watts, and for a while, Skid Row. In the areas where I lived, career options were limited to crime, pumping gas, bagging groceries, prison and death. So when I said I was going to be a writer, nobody believed me. Kids like me didn't become writers. The popular conception was that writing was an ivory-tower profession practiced by well-educated folks in smoking jackets who wrote while reclining on Macassar couches. My world did not connect with that world at any two contiguous points. I was a street rat.

Then, one day, I stumbled upon an anthology by Harlan Ellison, a self-professed street rat who ran with a street gang, was bounced out of college, and told repeatedly by teachers and others that he would never be a writer.

It was the first time I was able to connect to someone who came from the world I lived in, who had – through perseverance, talent and sheer force of will – made it as a writer.

From that day on, I collected everything I could find by him. Every magazine article, every anthology, every essay, every introduction. His introductions reinforced the concept of writing as a job of work, and that it didn't matter where you came from as long as the words were there and you never stopped fighting for the integrity of those words. Those pieces sustained and nurtured me through years when I might otherwise have given up.

Fifteen years after discovering that first book, I got to meet and gradually, slowly, become a friend to Harlan. I dedicated much of my life to paying back just a little of what he had, unknowingly and unwittingly, done for me. There are many stories I can tell, and some I cannot, about those years. But this one very small story I will tell because it illuminates the man behind so much myth.

Harlan and his wife Susan had taken several of us out to dinner in downtown Los Angeles. Later, with Harlan at the wheel and me riding shotgun because he always made sure I had that seat due to my height, we were driving back through some of the sketchiest and most gang-run parts of town because a) this was the fastest route and b) Harlan was fucking fearless. It was clear from the dealers and others eye-fucking us as we drove past that we weren't supposed to be there, and wherever we were going, we'd best just keep going there.

Then, on the right, we passed a homeless woman sitting by herself on the curb, one hand covering her face, the other on the shopping cart that held her few possessions. She wasn't looking for a handout or asking for money. Just exhausted and tired and, though you could not see her face, clearly in tears. At the speed Harlan was driving, it was only a glance as we passed.

Harlan hit the brakes. Glanced in the rear and side mirrors. "Goddamnit," he said, "she's all alone." He punched the steering wheel, then – an inner decision made – got out of the car and walked the half block down to her. We didn't know what the hell to do any more than the guys watching from the shadows.

I popped the door enough to hear what was being said, and to be ready to jump in if anything went wrong.

"Are you okay?" he said. "Do you need anything? Can I do anything?"

She shook her head, but I could not make out her words.

"It's gonna be okay," he said. "You'll be all right."

Then, with an economy of motion, so no one else would see what he was doing, he reached into his jacket, fumbled one-handed with his wallet, and pulled out some bills. Then he carefully slipped the money into her hand, sheltering the move from view.

"Don't let them see you have this, okay?" he said. "Go get something to eat. Maybe a place to stay for the night. You're not alone."

Then he straightened and came back to the car. He didn't acknowledge it but when I glanced over at him I could see that his eyes were moist. He didn't say anything else, and we continued north into the valley.

I know many fine people, good and caring and charitable. But I cannot think of anyone else who would have had the perception to see her, the compassion to stop for her, or the courage to walk out into a no-man's land where he could have been shot and robbed to make sure she was all right.

That was my friend Harlan.

"You're not alone."

That was what his words told me when I was fifteen and very much needed to hear it.

"You're not alone."

It's what he told a complete stranger decades later, and in so doing gave her a moment's light and hope.

"You're not alone."

It's what he wrote about in every essay, every introduction, every television episode and every short story. Despite the night and the fear and the failure and the thugs and the danger and yes, the death we face: we are not alone.

Harlan is gone.

And those of us who knew him must try, very hard, to remember that we are not alone.

It's not going to be easy. Not for a while, at least.

But we'll get there. Because that's what he would have wanted.