Posted in: Comics | Tagged: Comics, entertainment

Aleister & Adolf And The Symbols That Control Us

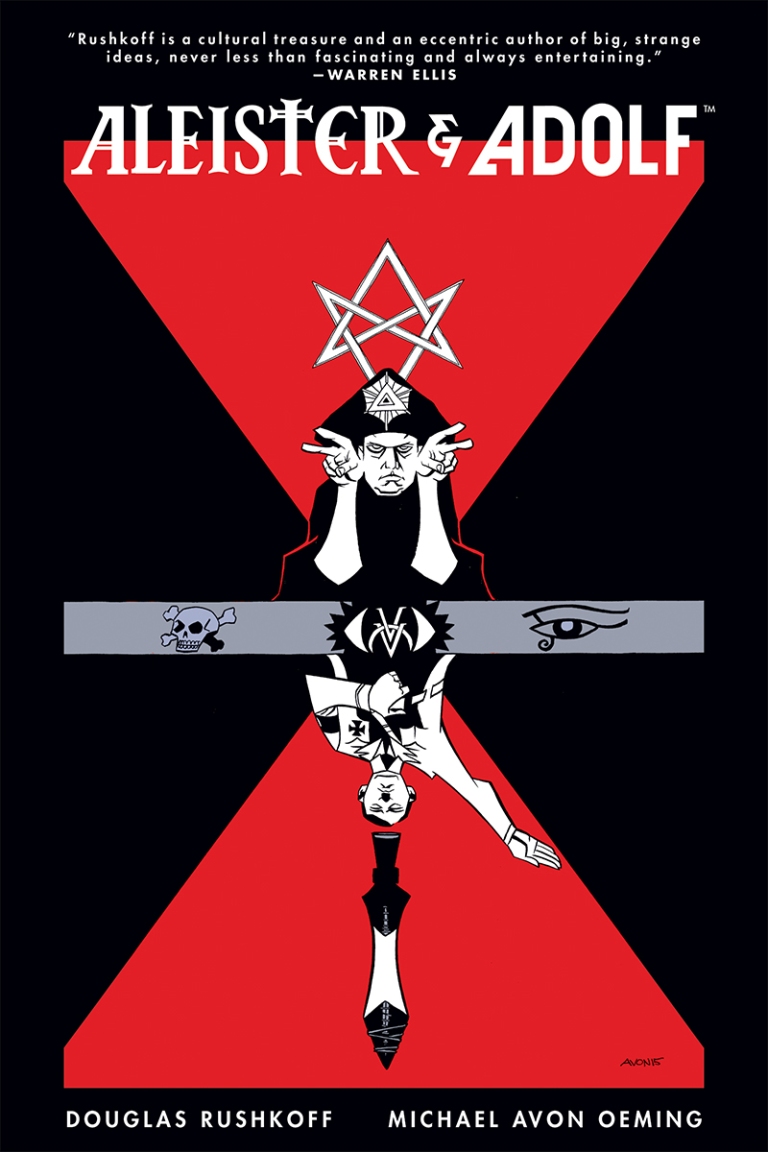

As one of the weirdos who has read about the strange life of Aleister Crowley, but one of the masses who has seen programs about Adolf Hilter's interest or even obsession with the occult on TV, I was naturally inclined to see what the new graphic novel Aleister & Adolf was about. But considering its author and artist—Douglas Rushkoff and Michael Avon Oeming respectively, I knew if I didn't pick up the book I'd regret it. I wagered that Rushkoff's ideas about media and symbolism would be picking up on the invention of modern propaganda under the Nazi regime and combined with Oeming's emotive and often highly symbolic artwork, the book would have something significant to say. Published by Dark Horse, the book also features some excellent and challenging work from Nate Piekos on letters.

I didn't count on reading it the day after the election in the USA, and putting it down to immediately see swastikas appearing in nearby Philadelphia and Sieg Heil tagging popping up elsewhere in conjunction with the KKK supported president elect. The timing was horrific and meaningful. I bought the book one week earlier during a time where the ideas of the book seemed cautionary, a lesson from the past to remember, and finished reading it in a world where it felt we were simply resuming the battle of symbols as a battle for dominance of ideology.

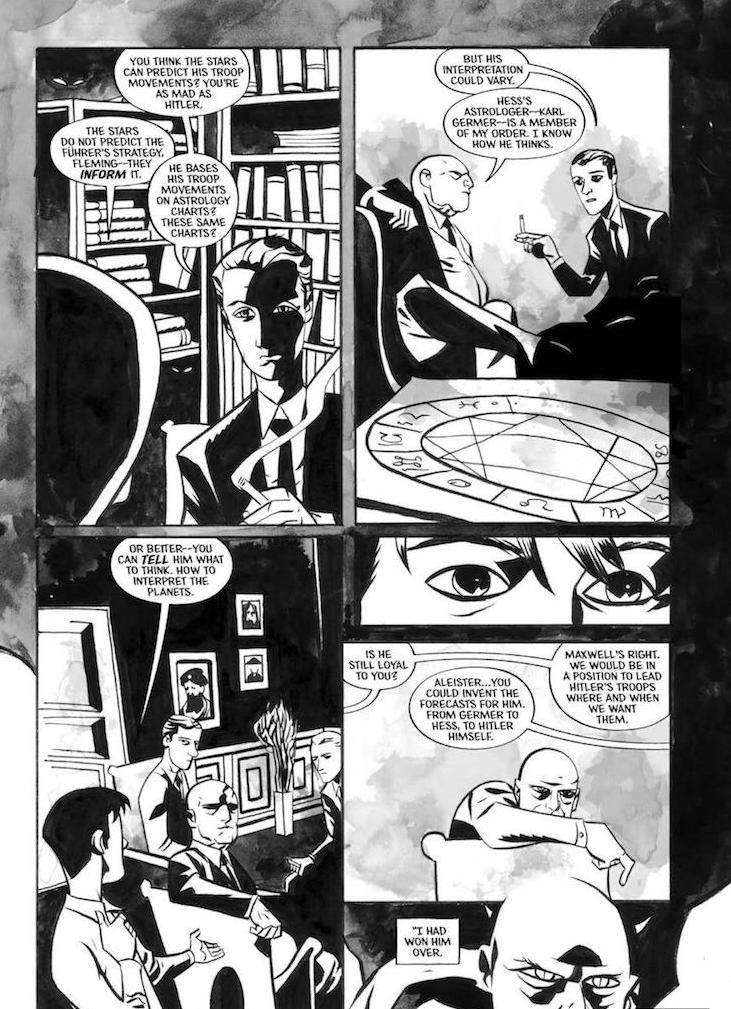

However, it would be unfair for me to read this book simply in the context of events of the past few weeks—it has an even bigger scope. It blends historical fact with rumor and fiction to build a compelling, dark fever dream of the struggle for symbols to invoke power, and the more quantifiable use of misinformation to encourage vulnerability in Nazi movements during World War II. The story follows a young American journalist, Roberts, who infiltrates Aleister Crowley's inner circle of practitioners of ritual magic and confidants in order to represent American interests in tracking down an occult object Hitler is rumored to possess—the spear that pierced the side of Jesus Christ on the cross. But once around Crowley, he falls into the world of magic and political intrigue very hard, and with little resistance. He sees the need to influence belief in order to influence the war.

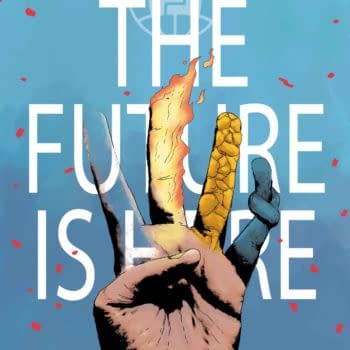

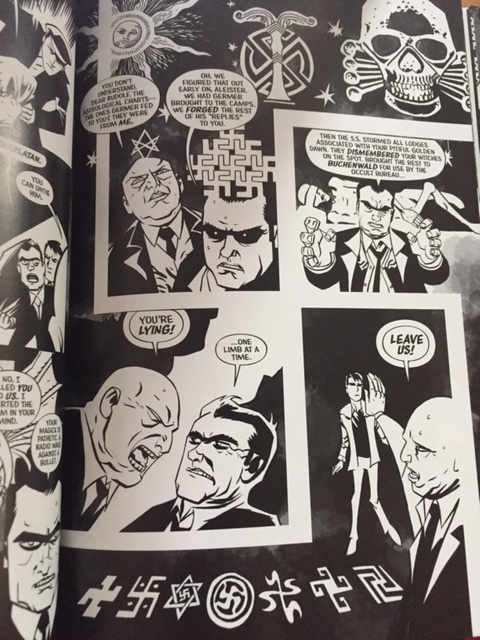

If this book were purely fantasy, it would establish the rules of its own universe and the reader would be obliged to accept them and keep reading, or reject them and put the book down. Even though this book has heavy historical elements mixed with things that are less firmly grounded, for the purposes of comic storytelling, you are obliged to make the same choice as reader. What helps immensely with this decision is the fact that Rushkoff and Oeming set up the rules and assumptions of this book very clearly, and directly address the power of belief, whether or not one "actually" believes magic is possible. Crowley may set out to create "sigil" symbols of power over the Nazis by creating sex rituals, and that may or may not repel you as a reader, but you will be convinced that symbols do have power through the course of the book and reflect on the way they shaped WWII as well as current daily life. In fact, you are likely to start understanding a little better your own subconscious reactions to symbols like the swastika or Winston Churchill's famous "V for Victory".

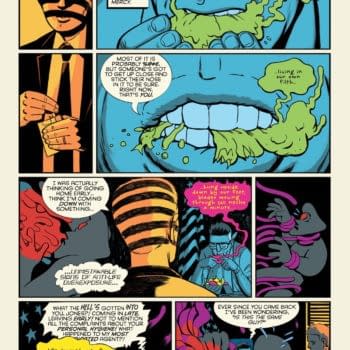

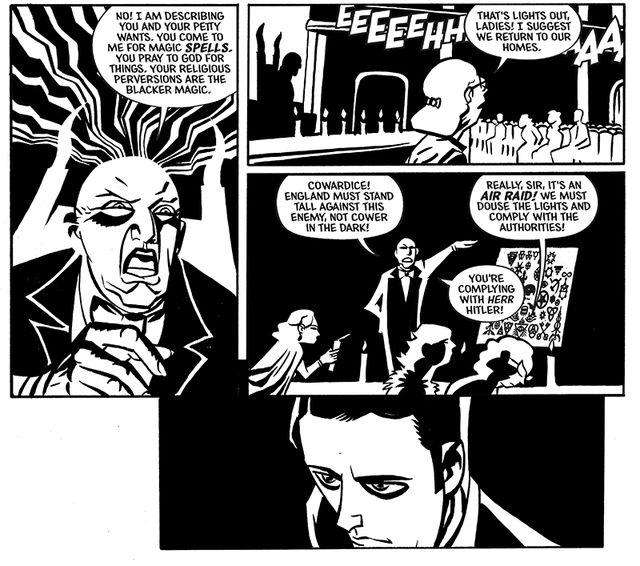

I've been exploring the intellectual and social aspects of the book, but does it make for a good story? Yes, it makes for a great horror story, in a way. It's like reading a myth or fable version of World War II, walking around behind the curtains of historical reality, and seeing events re-cast in broader, even more emotive terms. We also have a protagonist who we can watch becoming more and more involved in trying to influence the ideas behind the war, believing he is doing the "right" things, and yet moving further from the shore of a firm foothold on reality. We can follow the pros and cons of obsession, even if one seems on the right side of history. Oeming creates a fantastic black and white world of London streets, dark inner chambers, intense intentions and reactions in his characters, evoking a time of newsprint, grainy news reels, and even the stark newness and disjointedness of Roberts' perspective on Crowley and his political allies.

I've been exploring the intellectual and social aspects of the book, but does it make for a good story? Yes, it makes for a great horror story, in a way. It's like reading a myth or fable version of World War II, walking around behind the curtains of historical reality, and seeing events re-cast in broader, even more emotive terms. We also have a protagonist who we can watch becoming more and more involved in trying to influence the ideas behind the war, believing he is doing the "right" things, and yet moving further from the shore of a firm foothold on reality. We can follow the pros and cons of obsession, even if one seems on the right side of history. Oeming creates a fantastic black and white world of London streets, dark inner chambers, intense intentions and reactions in his characters, evoking a time of newsprint, grainy news reels, and even the stark newness and disjointedness of Roberts' perspective on Crowley and his political allies.

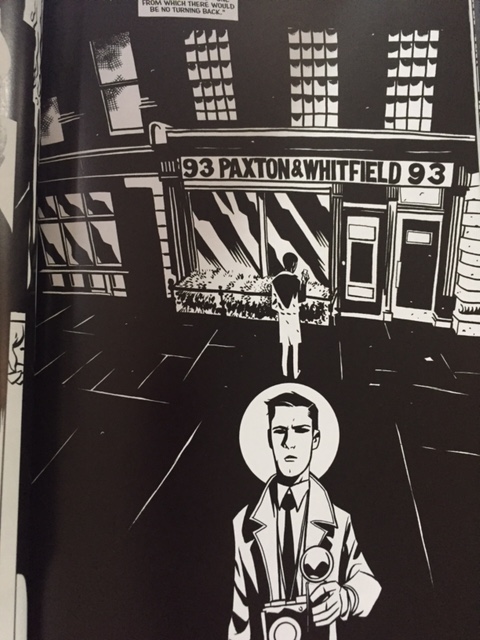

Particularly winning are Oeming's layouts which are often experimental, strangely spell-like at times as you find yourself caught in loops that keep you on the page, and quite overtly heavy on desired mood. One page's panel layouts form a swastika, in fact, but one that struck me the most shows a reverse shot of Roberts outside Crowley's building about to enter for the first time at the top of the page and a front shot of Roberts facing the door at the bottom, with a kind of halo of light around his head. The fact that the arrangement is against convention in a way—I'm more used to see someone's face and then a reverse shot rather than the other way around—sets a surreal tone, and then the fact that there are no visible lines dividing these "moments" into panels seem to render the page more of a spread. The truism is that a comic panel can't present more than one action at once, though we all know spreads can. This page stands midway between the two and seems to accomplish an eerie amount by doing so.

This 88 page story (with included sketchbook) feels like a highly compact tour of the dark undercurrents of modern human history. It poses another way to look at things that attempts quite firmly to reveal some truths about how power operates through the images we see every day. It's not a comfortable lesson, necessarily, but it's an empowering one for readers. And it seems like right now, at a time of renewed emphasis on slogans and symbols, this book has become more important than ever.