Posted in: Comics | Tagged: andy mangels, Comics, gay, howard cruse, lgbt, LGBTQ, stuck rubber baby, Underground

Andy Mangels Remembers Howard Cruse and Talks About His Legacy

Prominent gay comic book creator, activist and commentator, Andy Mangels, has shared a few words with Bleeding Cool over the passing of fellow comics creator Howard Cruse yesterday, at 75, after being diagnosed with cancer. Mangels writes in Memorium about Andy's life, his world and planned future projects that still may see fruition

HOWARD CRUSE: A REMEMBRANCE May 2, 1944 — November 26, 2019

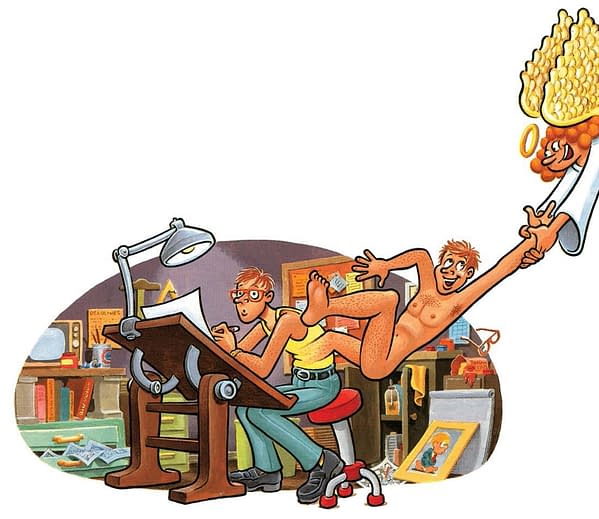

Upon their passings from this plane, many artistic geniuses are lauded for their body of work, and occasionally for their temperament. Howard Cruse, whose work spanned six decades of publication in and around the comic book industry, will be lauded — and rightfully so — for his genius work with the graphic semi-memoir Stuck Rubber Baby and for his collections of Wendel cartoons and other stories, but his temperament was as clear as his work was detailed. Despite the battles he faced as the first openly gay male in underground comix in the 1970s, Cruse never lost his temper without first resorting to wit, and his wisdom and cool demeanor led those who met him to see him as a wise mentor. Cruse charmed everyone; even on the internet, it would be hard to find anyone with a negative thing to say about him or his talent. The talent was prodigious, ranging from stories he wrote and drew with bold thick-lined cartoonish art to heavily cross-hatched, intensely-detailed realistic art.

Born in Springville, Alabama in 1944, Howard Russell Cruse was the son of a preacher. He loved Little Lulu comics as a child, and began drawing comics himself as a young child, including the adventures of an elf named Landie Lucker. Although he read other humor and funny animal comics, Cruse subscribed to Little Lulu until his college years, His first published work was when he was 13, writing and drawing a strip called "Calvin" in the weekly St. Clain County Reporter, and later the strip "Reuben" for a student newspaper from 1960-62. Through the sixties, he drew for theatrical programs, did editorial cartoons, and continued trying to sell newspaper strips to the syndication market. He also grew enamored of a different kind of comic: Mad Magazine, under the editorship of Al Feldstein.

By 1971, Cruse has debuted a strip titled "Barefootz" for a college newspaper, and he began exploring the open-minded world of underground comics. He also tried to have a heterosexual relationship with a girl in college, resulting in the pregnancy he would later recount in Stuck Rubber Baby. His baby daughter was given up for adoption by her mother. Experimentation with LSD led to more surrealism in Cruse's work, and he began submitting work to Kitchen Sink Press, the underground publisher. Kitchen Sink eventually published his first Barefootz collection (in 1975), and Howard dabbled in playwriting, television production, and even puppetry over the next several years. Further underground comix work continued as well.

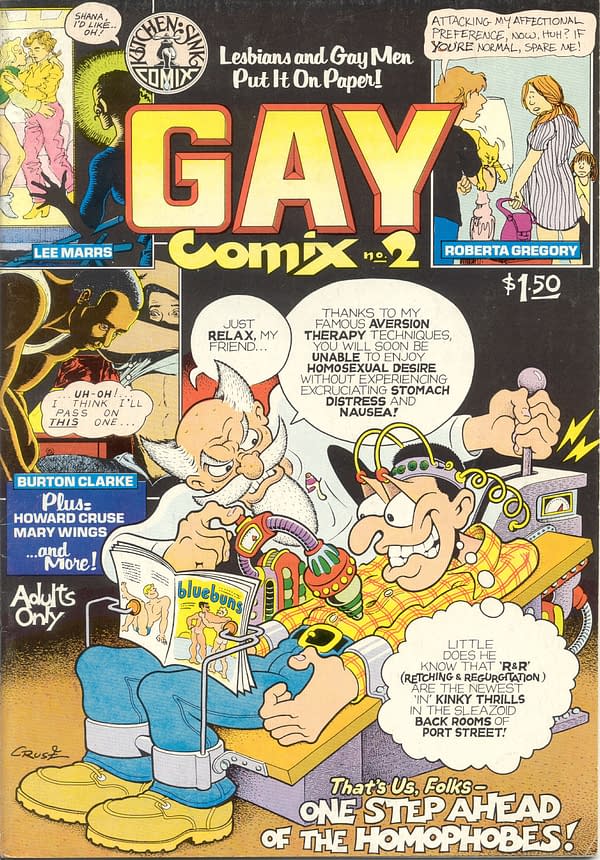

In 1976, Cruse devoted part of an issue of Barefootz Funnies to a story, "Gravy On Gay," which was the cartoonist's first venture into gay topics. He was inspired by Mary Wings' Come Out Comix in 1973, and the erotic anthology Gay Heart Throbs and Roberta Gregory's Dynamite Damsels, both also in 1976. Cruse didn't yet fully commit to being "out" in an industry that had nobody willing to create gay content under their own names, but he didn't hide it either. Publisher Denis Kitchen asked Cruse if he would be willing to edit a new Gay Comix anthology for Kitchen Sink, and Cruse agreed. In September 1980, the first issue of Gay Comix appeared, featuring Lesbian and Gay cartoonists creating comics specifically for their community. Cruse edited the first four issues, then turned editorship over to Robert Triptow (who edited #5-13, from 1984-1991, including a move to new publisher Bob Ross). Andy Mangels took over Gay Comix, changing the name to Gay Comics with issue #14, and ran it from 1991-1998's issue #25 (plus one Special).

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Cruse's work was not only seen in the undergrounds, but by a diverse number of fans. He illustrated Topps' Bazooka Joe Bubble Gum Comics inside the wrappers. He illustrated David Gerrold's columns and art-directed for Starlog magazine, and created Count Fangor and spot illustrations for early issues of Fangoria magazine. He also wrote and illustrated the "Loose Cruse" column for Comics Scene magazine, and created the Doctor Duck strip for Bananas magazine. He drew for Playboy, Heavy Metal, ArtForum International, and The Village Voice. And in the gay world, even once he had left Gay Comix, he drew the regular Wendel strip for The Advocate newsmagazine (from Jan 20, 1983 to 1985 and 1986-1989), wherein he tackled long-term characters who lived in a realistic up-to-date gay world, including homophobia from Republican President Ronald Reagan, and the AIDS crisis.

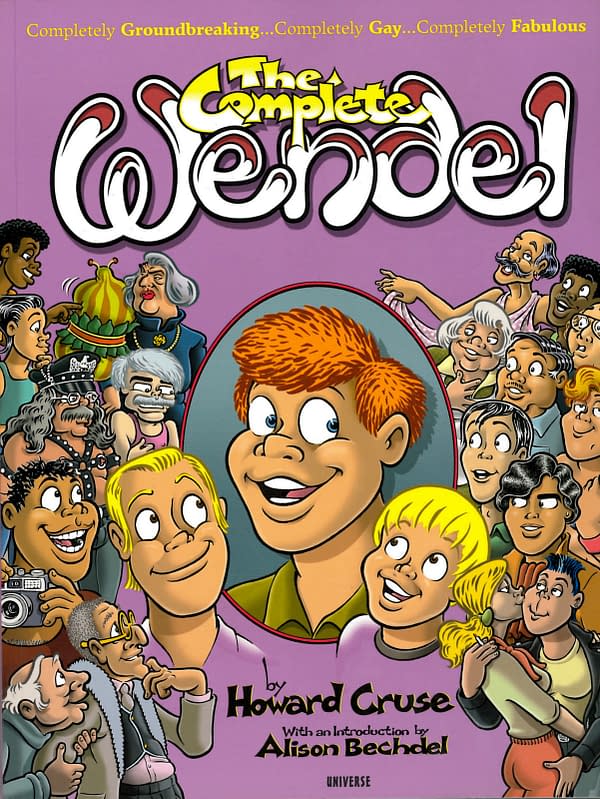

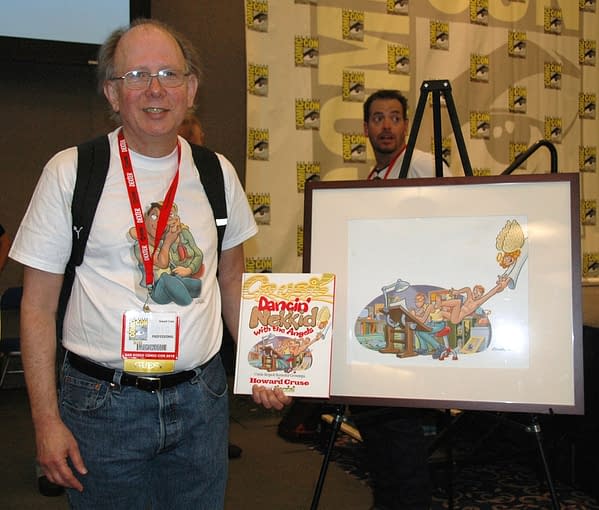

In 1986, Renegade Press released Barefootz: The Comic Book Stories, the first collection of Cruse's work. Dancin' Nekkid With The Angels collected many short stories from Gay Comix and other sources in 1987, from St. Martin's Press. The same publisher released Wendel On The Rebound in 1989, and Kitchen Sink released Wendel Comix in 1990, while Fantagraphics released Early Barefootz the same year. In 2001, Olmstead Press released Wendel All Together, while in 2009, Nifty Kitsch Press brought out From Headrack to Claude: Collected Gay Comix. In 2011, Universe published The Complete Wendel, and in 2012, Boom! released The Other Side of Howard Cruse collection. Cruse recently self-published a book called Felix's Friends, a "story for Grown-Ups and Unpleasant Children."

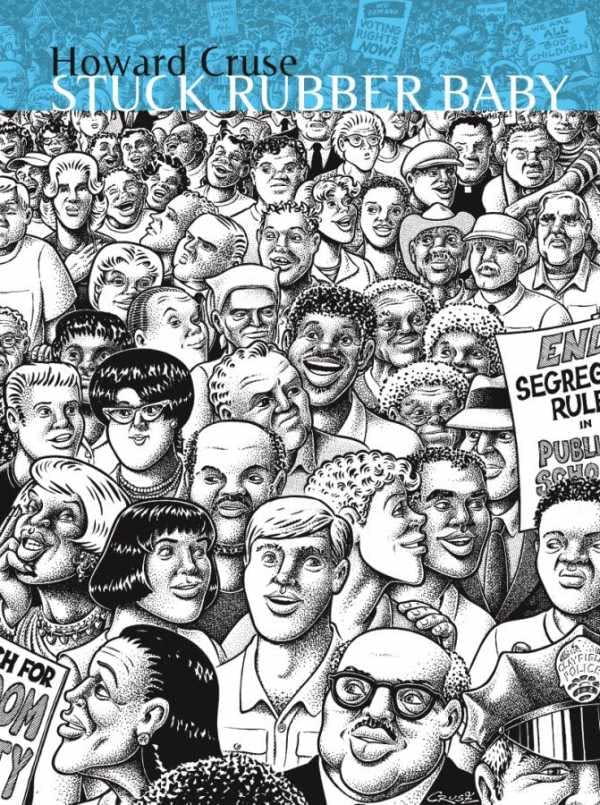

For many years, Cruse worked on the semi-autobiographical graphic novel Stuck Rubber Baby for Paradox Press, an imprint of DC Comics. The book was finally published in 1995 to immense critical acclaim. Mainstream press, librarians, teachers, and comic readers alike all praised Cruse's work for its raw emotional honest and insanely detailed art even as he wove a story about racism and homophobia in the south, and the intersection of the Civil Rights movement with personal coming-of-age. Stuck Rubber Baby would be awarded both the prestigious Harvey Award and Eisner Award and United Kingdom Comic Art Award for Best Graphic Album, and the work would be republished in 1995 by Harper Perennial, and Vertigo in 2010.

In the time since Stuck Rubber Baby, Cruse has not produced any long-form comic work, though he has continued to draw for comics, political and humor magazines, newspapers, CD covers, Broadway posters, erotic magazines, and more. Comic-Con International awarded Cruse their prestigious Inkpot Award in 1989. Cruse has curated art shows for LGBTQ cartoonists, and has been the subject of art exhibits of his work worldwide, including a recent summer 2019 show in Brussels. He has spoken at colleges and high schools, at symposiums and comic cons, and at the biannual Queers and Comics educational conferences (in New York and San Francisco).

In between all of the creativity, Howard met Eddie Sedarbaum around 1979 in New York and the two have been inseparable since; they were finally legally wed in summer 2004. Cruse and Sedarbaum have been active politically in New York and in their home area of northwestern Massachusetts. Their relationship was discussed by Sedarbaum in the 2002 TwoMorrows book by Blake Bell, I Have To Live With This Guy.

Cruse's final published comic work is in Northwest Press's horror anthology Theater of Terror: Revenge of the Queers, released in 2019 He is extensively profiled in the upcoming 2020 documentary feature film No Straight Lines, alongside other LGBTQ creators. Meanwhile, Stuck Rubber Baby is about to have a new 25th Anniversary Edition, from First Second on May 12, 2020. Cruse is survived by husband Eddie Sedarbaum, older brother Allan, and daughter Kimberly Kolze.

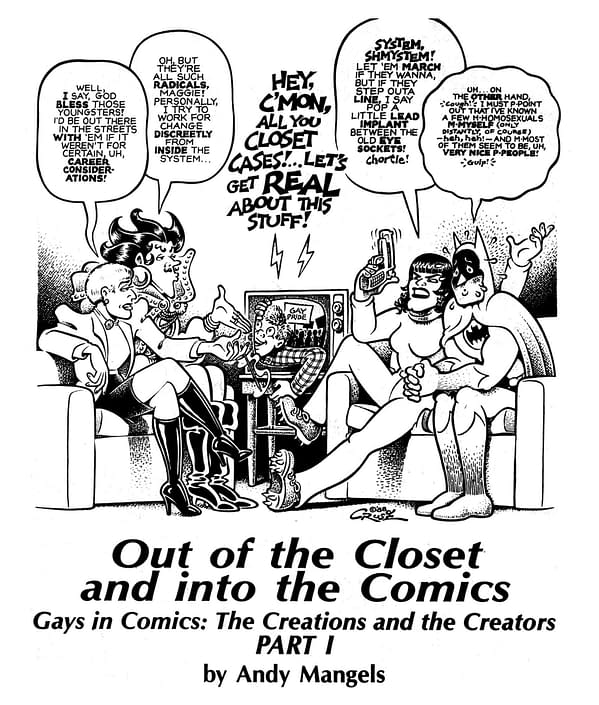

The afore-written tells you much about the legacy of Cruse's work and career, but little about his mentorship and temperament. I was 13 or 14 when I first saw Gay Comix #1 on the stands at a store in Long Beach, California. I could only afford a furtive glance or two at it then, but it told me that not only were there gay comics, but there were also gay people creating comics. In April 1987, I came out, and saw no one like me in the comics themselves, at the comic store in which I worked (Pegasus Books in Beaverton, OR, also the literal birthplace of Dark Horse Comics), or in the magazine for which I wrote (Fantagraphics' Amazing Heroes). Through Fantagraphics, I got hold of Howard Cruse, and he gave the young 20-year-old proto-gay all the attention and advice over the phone that time would allow. When I proposed — and wrote — the massive two-part article "Gays In Comics: The Creators and the Creations" for Amazing Heroes in the summer of 1988, not only was Howard the ONLY person in the industry that I interviewed who would identify as gay, but he also provided a lovely illustration for the article. He later gifted me the artwork, which hung in my office for over decades.

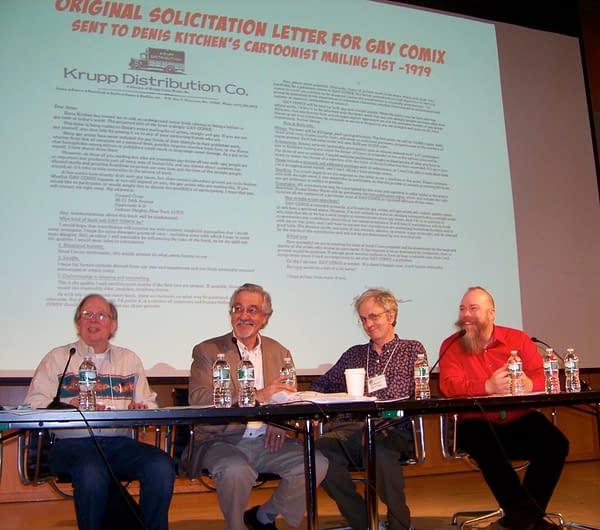

Although we talked on the phone (and later emailed) often since 1987, Howard and I only got to see each other a few times in person. In 1989, I got to host him on the second Gays In Comics panel, and in 1996, I got to host him on the ninth year of the panel. He also appeared in 2010 on the 23rd year for the panel, and sent a video for 2012's 25th anniversary. We were at the Boston Outwrite conference in 1992, and I believe that he was part of a particularly crazy Gay Comics signing at the national March On Washington in 1993. Most recently, Howard reunited with Robert Triptow and I as guests of honor at the first Queers and Comics academic conference in 2015 in New York (Howard also did a keynote speech).

Of late, Howard, Robert and I have been doing preliminary work on putting together The Complete Gay Comix/Comics for a publisher, to collect all the issues. We had collectively been tracking down contributors, and enjoying the solidarity of each others' company, even as we complained some of the "historians" that have recently come along to present skewed views of history. As "eldest statesman" and "interview subject #1," Howard had always been quick to credit Robert and I for our extensive and groundbreaking work in the field, and for the opportunities we created for LGBTQ creators worldwide. We, in turn, bowed down to Howard's history and birthing of "openly" gay cartooning.

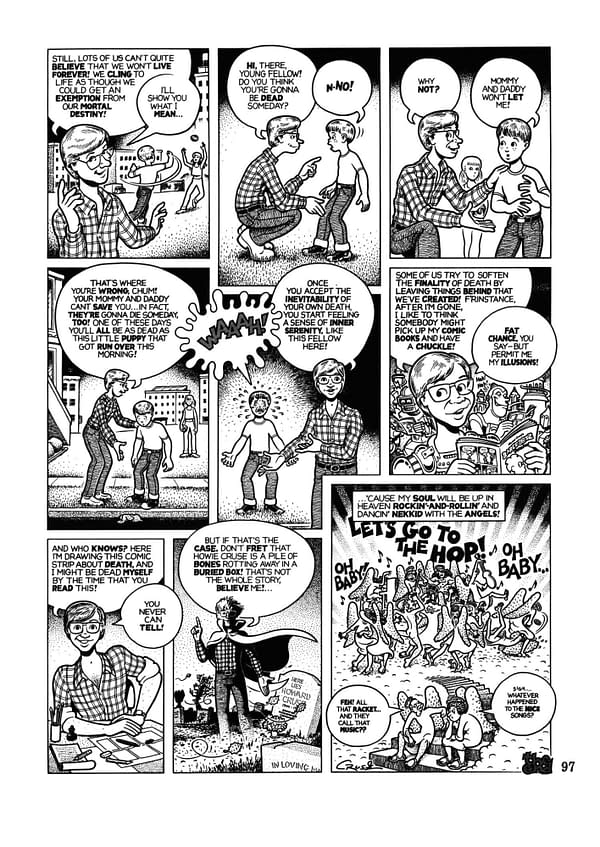

And now, days before Thanksgiving, Howard Cruse is no longer here. To say that this news devastated me — and many professionals and fans in the comics world who had loved the man and his work — is a vast understatement. In one of his strips, "Death" (which appeared in Dancin' Nekkid With The Angels) he presaged his own death. "After I'm gone, I like to think somebody might pick up my comic books and have a chuckle! Fat chance, you say — but permit me my illusions!" He also promised that his soul would be up in heaven, "Rockin'-and-Rollin' and Dancin' Nekkid with the angels!"

If there is any justice in this world for a talent as great as Howard Cruse's, and a soul as forthright, readers will go pick up his books and have a chuckle, and his soul really will be dancin' nekkid with the angels.

— Andy Mangels, November 27, 2019

For some great Cruse reference:

- Howard's own site:

- Comic Book Creator #12 (TwoMorrows, ) 46-page cover story interview

- The Comics Journal #111 (Fantagraphics Sept 1986) 32-page cover story interview

- The Comics Journal #182 (Fantagraphics, Nov 1995) interview

- 1988 The Advocate interview (March 15, 1988)

- 1998 Amazing Heroes Gays In Comics articles

- 2010 Comic-Con Spotlight on Howard Cruse

- www.youtube.com/watch?v=NaTAXB_o7TM

- 2011 TCJ Talkies interview with Howard Cruse

- 2012 interview Comics Reporter

- 2015 Queers and Comics Keynote Speech and Gay Comix Reunion

- 2018 The Stonewall Oral History Project – Howard Cruse