Posted in: Comics, Manga | Tagged: anime, apocalypse, Attack On Titan, devilman, devilman crybaby, go nagai, Hajime Isayama, hideaki anno, manga, neon genesis evangelion, netflix

Attack on Titan's Apocalyptic Climax is Part of a Common Trend

THE ARTICLE CONTAINS SPOILERS FOR THE LAST CHAPTER OF ATTACK ON TITAN.

Attack on Titan just ended its 11-year manga run, and that story will be adapted for the finale of the anime series this Winter. In the climax, the heroes had to prevent the big bad from triggering an apocalypse that didn't just destroy the world but would rewrite Reality itself. This is actually a very common trope in a lot of manga and anime.

This trend began in the 1970s and has continued from time to time. It might have begun with Go Nagai's series Devilman, which evolved from a supernatural superhero story into a full-blown apocalypse with the hero fighting an ultimate battle with Satan himself, who's the big bad of the series. He lost, humanity is exterminated, and Satan, who actually loves him, is left alone with his bisected corpse on a devastated Earth. This was possibly the darkest and most nihilistic ending in the history of Comics. A new, faithful anime adaptation, called Devilman: Crybaby, is now on Netflix. Hajime Isayama draws on that series for his climax to Attack on Titan.

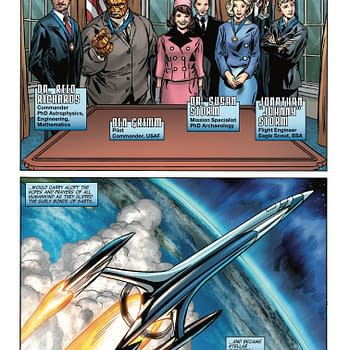

The trope became big again in the late 1990s in manga and anime when Hideaki Anno ended Neon Genesis Evangelion on an ambiguous note where the emotionally devastated and dysfunctional hero Shinji Ikari is the one with the choice to completely rewrite the universe and all of Time and Space. Since then, a huge number of epic manga and anime series have used that trope. So have Marvel and DC Comics, who practically do that every year in their crossover events. The difference is, when a villain in Western comics wants to take over the world or all of reality, it's usually because they're megalomaniacs and want power. They hardly ever talk about what they would use that power for. The power is usually just a McGuffin for the heroes to keep them from using. There's a deeper, more existential reason for the baddie wanting the power to change the world and reality itself in Japan. A Japanese big bad is usually a disillusioned idealist fallen into nihilism. He thinks the world sucks so much he wants to rewrite it into his idea of utopia. Eren Jaeger in Attack on Titan uses the power of the Founding Titan to threaten the world and sets himself up so that his love Mikasa can save the world by killing him, leaving only the new reality that there are no more Titans. It even references Devilman in having a hero carry the decapitated head of their dead love.

The fantasy of changing reality seems to spring from a deep sense of helplessness in the state of the world. It's a fantasy about playing God. These manga villains don't want to talk over the world. They want to change it and mold it to their idea of a better world. It's villainous because it's the epitome of hubris, and the bad guy is willing to murder literally billions of people to succeed. It's also often remarkably convoluted and melodramatic. Manga editors are certainly encouraging creators to plot for this long arc in order to give a series a point to work towards and an ending to plan for. You can't have a more epic climax to a series than all of reality under threat. Attack on Titan is the latest example of this trend, and it certainly won't be the last.

And next winter, anime fans will get to watch the animated version of this climax.