Posted in: Comics | Tagged:

Big-Boy Philosophy

Chris Gavaler and Nathaniel Goldberg write: Bill Maher, an American talk show host, insulted comic book legend Stan Lee and the Internet was outraged.

Now that the furore has died down, it's become apparent that Maher didn't actually insult Lee. He insulted his fans—the millions who, according to Maher, Lee inspired "to, I don't know, watch a movie, I guess."

Maher didn't insult Lee's comics either, which Maher read as a kid. Nevertheless, he explained, "the assumption everyone had back then, both the adults and the kids, was that comics were for kids, and when you grew up you moved on to big-boy books without the pictures." He was right about that assumption. Maher was born in 1956. When he was reading them in the late 60s—a peak moments for Stan Lee and Marvel—comics were still targeted at twelve-year-olds. It wasn't till the 90s that the average reader tipped past twenty.

Maher was thirty-six in 1992 when Art Spiegelman's Maus won a Pulitzer. He said nothing about that. Neither did he insult the Booker prize committee after Nick Drnso's graphic novel Sabrina received a nomination earlier this year. In fact, Maher wasn't objecting to comics generally but to the subgenre of superhero comics specifically that Lee helped popularize. Nor is he alone. Alan Moore, the most critically acclaimed author of the genre, called most superhero stories "unhealthy escapism" and a "cultural catastrophe," even though his Watchmen made Time magazine's 100 all-time best novels list.

Maher saved his most pungent punch, however, not for the casual comic book reader but for academic authors writing about comics. He was annoyed at professors "using our smarts on stupid stuff." Maher laments that "twenty years or so ago, something happened—adults decided they didn't have to give up kid stuff. And so they pretended comic books were actually sophisticated literature. And because America has over 4,500 colleges—which means we need more professors than we have smart people—some dumb people got to be professors by writing theses with titles like Otherness and Heterodoxy in the Silver Surfer."

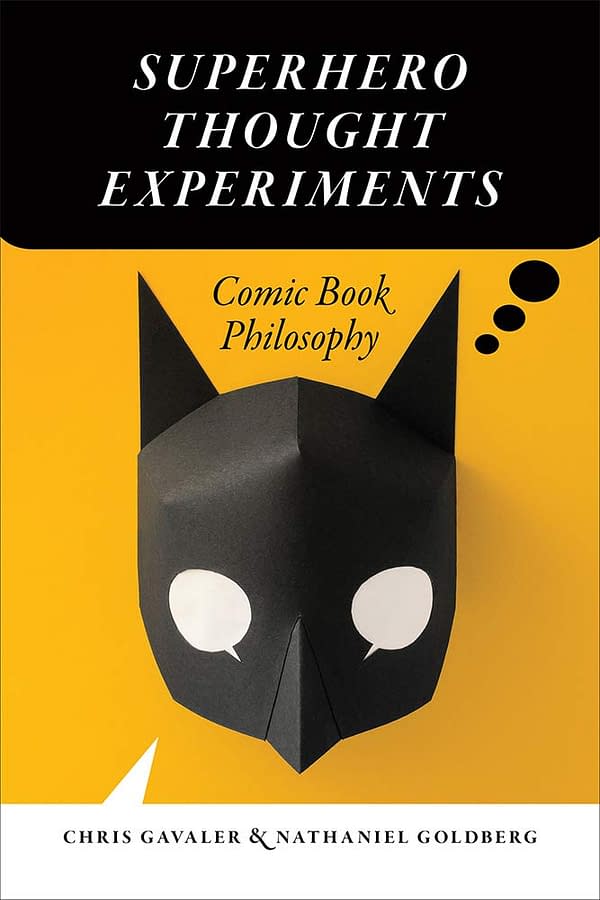

Maher invented that title, but it's not implausible—maybe not for a dissertation, but certainly for an article. Neither of the authors of this essay wrote doctorates on superhero comics, but we have co-authored academic essays with titles that Maher could have cited instead: "Dr. Doom's Philosophy of Time," "Economy of the Comic Book Author's Soul," "Loving Lassos: Wonder Woman, Kink, and Care." Worse, we even have a new book from a university press devoted entirely to explaining superhero comics and philosophy. There we ask perhaps the stupidest question of all: Was Stan Lee a philosopher?

For starters, other than etymologically as love of wisdom, "philosophy" is famously difficult to define. It's a priori system building for some, conceptual analysis for others, or foundational to other disciplines (perhaps) because it's the most general discipline, having been the Ur discipline, for others still. Whatever else it is, though, philosophy often trades in thought experiments.

Like empirical experiments, thought experiments involve testing a hypothesis in a controlled environment. In the case of philosophy, the environment involves holding other things constant while thinking internal thoughts rather than tinkering with external objects. Thought experiments introduce situations where a few key details are changed from how they ordinarily are to test particular philosophical views. What if an evil genius is tricking you into believing that the world around you is real when it isn't? What if on an alternate Earth everything is identical but for one almost undetectable detail? What if trying to travel to the past transported you to a different universe instead?

Any of these fantastical plots could have been the premise of one of Lee's superhero comic book. He sometimes gave artists at Marvel little more to work with. Except none of those thought experiments comes from comics. They're all written by highly regarded academic philosophers: René Descartes (1641), Hilary Putnam (1973), David Lewis (1976).

The list of potential "What If?"s seems endless. What if someone from the future returned to his childhood and told his past self about the future? What if someone's body slowly transformed from flesh into rock, but no one around to notice? What if a god were stripped of his memories and forced to live as a crippled human? Except these scenarios don't come from academic philosophy. They're all from superhero comics—The Defenders (1975). The Fantastic Four (1961), The Mighty Thor (1968)—and Lee had a hand in them all.

Admittedly, comics don't explicitly treat their scenarios as thought experiments, and Lee certainly didn't set out to experiment in thought in any meaningful way. Further, just as we'd expect, actual analysis is done better by academic philosophy than by comic books. Nevertheless, academic philosophers can come up short. As Ross P. Cameron, himself a philosopher, explains, "a typical fiction tends to be much longer than your typical thought experiment and hence can present you with a more detailed scenario." Likewise, Johan de Smedt and Helen de Cruz (philosophers too) argue that, though both typical philosophical thought experiments and fiction rely on similar cognitive mechanisms, fiction "allows for a richer exploration of philosophical positions than is possible through ordinary philosophical thought experiments." The exploration is richer not only because it's more developed, but also because readers of fiction are immersed in a way that readers of philosophy usually aren't. Smedt and Cruz continue: "Regardless of whether they are outlandish or realistic, philosophical thought experiments lack features that speculative fiction typically has, including vivid, seemingly irrelevant details that help to transport the reader and encourage low-level, concrete thinking."

These philosophers contrast typical thought experiments with the longer scenarios in novels, but their points apply even better to comics. Novels employ words to express ideas, while comics employ both words and images, and so reading a comic operates on an additional cognitive level. It can be both more immersive and more challenging due to its multi-media form. And Lee was so central to so many comic books over his long career that he had a hand in myriad thought experiments. So, yes, Stan Lee was a philosopher of sorts.

Of course, Maher could complain that philosophy involves "using our smarts on stupid stuff." He wouldn't be the first to do so. The liberal arts, and humanities particularly, have been called worse. The Athenians accused Socrates of corrupting the youth, and while Stan Lee's Spider-Man or Fantastic Four comics are nowhere near as penetrating or erudite as Plato's Socratic dialogues, comics have been accused of corrupting the youth too. Eventually, Socrates' youthful students grew up. One of them was Plato. According to Maher, "adults decided they didn't have to give up kid stuff" in the form of comics. Fortunately, Socrates' youthful students didn't give up philosophy either.

***

Nathaniel Goldberg is Professor of Philosophy and Chris Gavaler is Associate Professor of English at Washington and Lee University. Their Superhero Thought Experiments was published this month by the University of Iowa Press.