Posted in: Comics, Comics History | Tagged: ben day, Brother Jonathan, charles dickens, obadiah oldbuck

Fandom 1842: Happy 176th Birthday, Comic Books in America

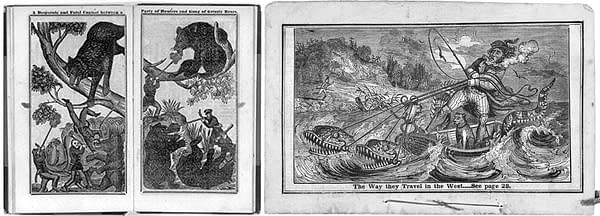

On September 14, 1842, a publication which has widely been considered the first comic book to be published in the United States of America was released by a publisher called Wilson & Co.: Brother Jonathan Extra No. 9, better known as the Adventures of Mr. Obadiah Oldbuck. It was an English translation of an 1837 Swiss comic called Les Amours de Mr. Vieux Bois, by artist Rodolphe Töpffer.

It's worth pointing out something that notices of this event usually avoid mentioning: Brother Jonathan Extra No. 9 used printing plates acquired from the publisher of a British bootleg edition, which was itself copied from a French bootleg of an authorized French-language edition printed in Geneva, Switzerland. So, comics is off to a bad start in terms of respecting creator's rights. The non-existent international copyright law of the era is largely to blame here, publishers justified it because it was legal, and American publishing empires of all kinds were built on top of the fact that non-citizens could not copyright their works in the United States for most of the 19th century. Some of those empires still exist in some form to this day.

That aside, Brother Jonathan Extra No. 9 was also not by any stretch of the imagination the first published comics material in this country. The popularity of the almanac format had exposed much of America to comics and illustration art since colonial times. While not pure comic books as we know them today, these almanacs did sometimes contain both short sequential comics and comic panels, and it's pretty hard to argue against the notion that they are significantly more important to the genesis of the pop culture landscape in America than Obadiah Oldbuck has been. The work of Benjamin Franklin as a cartoonist is often overlooked in this area, and the cover of his first almanac in 1733 is a basic example of sequential comic art. Davy Crockett, the subject of many of the most popular of these almanacs, was virtually a super hero in the 1830s and 1840s, and one can make an excellent case that he was a comic book super hero at that.

Indeed, the explanatory blurb from the September 17, 1842 edition of Brother Jonathan describes the concept behind Obadiah Oldbuck as something with which the reader has at least some passing familiarity:

The reader has undoubtedly heard graphic narrations spoken of, and will be compelled to acknowledge that this work comes entirely under that description, for a more exclusively as well as eloquently graphic production it was never anybody's lot to see. In a word it is not a "story and pictures to match" as Jack Downing says, but a story told entirely with the graver.

Rodolphe Töpffer's importance as a comic artist is relatively well-tended territory which I'm going to leave to others for now, though I think Töpffer as "inventor of comics" overstates the case. The development of the medium throughout this period is dictated by the technological processes of engraving and printing, as much as it is by artistic innovation.

But Brother Jonathan Extra No. 9 is still incredibly important in the history of America's pop culture landscape. Not for what it directly inspired, but for the moment it was a part of, and the consequences of that moment. If one were to pick a single year to mark the true beginning of popular culture in the United States, 1842 would be that year. The Brother Jonathan Extra concept itself is also the beginning of cheap, paperbound fiction for the masses in this country. This was also the year that fandom began to emerge, organize, and actually held its first fan event. And it was the year of our first comic book, published in a form that we would recognize as a comic book in the modern day.

1842 is the birth moment of fandom in America, and comics were part of that.

Let me set the scene for fandom's first year with this description of Gotham from Brother Jonathan Extra #1, about the glories of Gotham from the perspective of an author of fiction:

Indeed the materials are so profuse that the author who deals in them requires neither invention nor imagination, but merely a fair talent for telling the truth takingly, for once he begins, he will find it scattered about him in rich confusion any quantity of the prettiest and most interesting little loves — murders — intrigues — sentimental suicides — broken hearts — secret associations — forced marriages — mysterious orphans — curious coincidences — midnight strangers muffled up in dark cloaks, and looking suggestive of Spanish stilettos — nay even of duels, conspiracies, and ghosts — that ever threw a blotter of white paper into a rhapsody, or astounded and captivated the reading public.

And then for characters, singlular, dinstinct and numerous, we stand pyramidically pre-eminent over all the world. Talk of London and Paris; they are not to be mentioned in the same day with New York; for whenever any son of a woman belonging to either of the former places finds he has a genius above the common, he is almost sure to be off to Gotham to speculate on it.

It's hard not to love that. It practically predicts 176 years worth of detective fiction, and is made all the more delicious by the fact that the story goes on to include a member of the Livingston family. The Livingstons had a very large manor in upstate New York at this time, you see. There were caves underneath this manor. One of Batman co-creator Bill Finger's ancestors, the first member of the Finger family to live in this country Johannes Finger, once lived on stately Livingston Manor, as a tenant. An unbelievably true tale for another day.

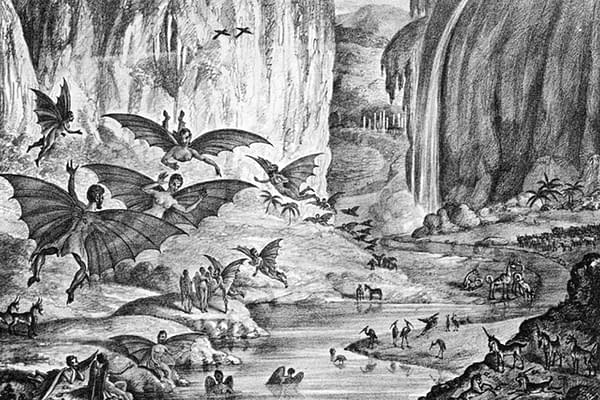

The co-publisher and printer of Brother Jonathan, Benjamin Henry Day, has a fascinating place in America's pop culture history himself. Day was a staunch advocate of producing cheap publications for the masses throughout his career, and before Brother Jonathan, started the first penny paper,which was also the first major "sensational" newspaper in the country, the New York Sun. You'll often see the Sun referred to as a tabloid, but I'm trying hard to avoid that here because the term tabloid also implies size and format. The Sun was not of that familiar format, but it certainly was sensational. It is perhaps best remembered today for publishing "The Great Moon Hoax", which was a widely-believed bit of fake news about the discovery of Batmen on the moon. The tale of these Batmen — they're really more like Man-Bats, I suppose — is itself a noteworthy footnote in comic book history, because a century later, future Batman editor and Man-Bat co-creator Julius Schwartz wrote a fanzine article about Benjamin Day's hoax, well in advance of his association with DC Comics.

Day moved on from the sensationalism of the New York Sun, but retained the enthusiasm and willingness to experiment that made Brother Jonathan the memorable success that it became during this era. He had authors he wanted to champion, he had rivals he wanted to best (in particular, Park Benjamin of the New World), and he was feeling his way towards a concept that his publishing peers hadn't caught onto, quite yet: Young America, fresh from its revolution and coming to grips with the meaning of democracy and capitalism, had an appetite for a different sort of fiction than the old world was accustomed to accepting. We wanted a relationship with the work and the people who produced it.

We wanted to be fans.

The February 5, 1842 edition of Brother Jonathan reads as sort of a foundational document of American fandom. The trigger for the sentiment behind this edition was the impending arrival of the biggest literary star in the world: Charles Dickens.

In an article titled Charles Dickens: Personal Respect vs Toading, Benjamin Day lays out the ground rules for fan/pro interaction. He tells his audience that this is not the same thing as discussing Oliver Twist or the Pickwick Papers around a dinner table with friends or family. A different approach is required:

[Dickens] is not to be treated to pasteboard ceremony, dinner-table civilities, ball room spangles, and fashionable hollowness, only. A modicum of these things is due to him by conventional usage. Respect for the author and the individual directs that a proper portion of the tinsel of "civilized life" should be woven in his wreath. But Americans cannot expect to masquerade before him through his whole visit.

He can find our moral, literal, social, and political Punches and Judys fast enough without aide. Let him have some chance to meet the people, and let the people meet him like men.

Let toadyism and ridiculous man-worship be sedulously avoided. Let ultra Americanism, and beggary of his good opinion be shunned. Let no apologies on the one hand be offered for what he may see, and no violent amor patriae and braggadocia be displayed on the other.

Don't behave before him like school children at an examination, or on the other hand patronize him, as if you were doing him a vast deal of honor. We owe him a heavy debt, for the amusement he has afforded, and the good he has done us. Show him that it is appreciated.

Remember that the author of Nicholas Nickelby and the Curiosity Shop eats, drinks, blows his nose; that he usually retires to bed, ay, actually retires to bed, and actually rises daily without the exercise of supernatural power; that he can say "how d'ye do?" without uttering an epigram, and order a scuttle of coal into his room without exciting a sensation.

The next article in this issue, The Boz Fete at the Park, revealed that Dickens had agreed to be present at a festival event in his honor, and that… the citizens of New York were invited. Numerous details about the particulars of this Boz Fete were forthcoming. For example, the stage of the theater was to be "highly embellished with various designs from the writings of "Boz", illustrating many of his striking, original, novel, graphic, familiar scenes. A full orchestra would also be engaged, with arrangements inspired by works such as Oliver Twist, Little Nell, Nicholas Nickleby, Curiosity Shop, and so on.

Tickets were $5 for the admission of a gentleman and a lady, and extra ladies' tickets were to be $2 each. Interestingly, "all fancy dresses are to be rigorously excluded," in keeping with the spirit of making it an event for the common fan, it seems.

By all accounts after the event, a good time was had by all, and Dickens himself was appropriately polite and appreciative at the end of it. However, despite Benjamin Day's ground rules for fandom, Dickens later revealed in private letters that he was overwhelmed by his American fans during this tour. He wrote:

I can do nothing that I want to do, go nowhere where I want to go, and see nothing that I want to see. If I turn into the street, I am followed by a multitude. If I stay at home, the house becomes, with callers, like a fair. … I dine out, and have to talk about everything to everybody. … I take my seat in a railroad car, and the very conductor won't leave me alone. I get out at a station, and can't drink a glass of water, without having a hundred people looking down my throat when I open my mouth to swallow.

But the success of the Boz Fete encouraged Benjamin Day down the path towards reaching a mass audience with such fiction. He was now ready to go all in on the idea of promoting certain British authors such as Dickens and Edward Bulwer-Lytton. He thought they would do quite well at a 25 cent price point vs the $1.50 that Harper & Brothers typically sold a hardcover for at that time.

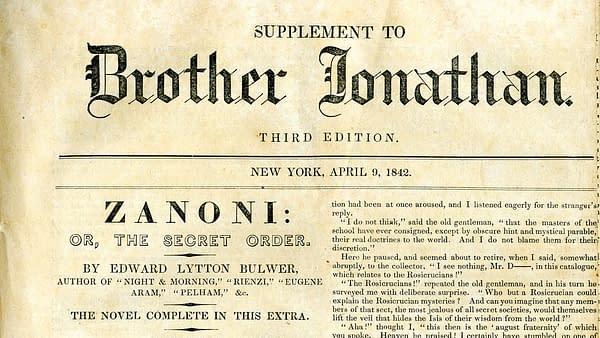

The first real test of the concept was to be Bulwer-Lytton's Zanoni: Or, the Secret Order. Unlike Dickens, Bulwer-Lytton's name is largely forgotten now, his work reduced to pull quotes such as "the pen is mightier than the sword", and "it was a dark and stormy night", among many others. Zanoni is very nearly what we'd call Lovecraftian today, however, and is remembered for its depiction of an archetype which he called "The Dweller on the Threshold", and to which he also assigned an even more familiar name: the spectre.

What happened on the day of Zanoni's release is perhaps one of the single most important moments in the history of mass market fiction in the United States. Brother Jonathan's Extra edition of Zanoni hit New York City like a bomb:

Wilson & Co's men were at work setting up the novel, which was printed and issued from the press in 36 hours from the time that the compositors began their work. This was the first complete cheap novel that had ever been published in this country. It was issued at five o'clock on the evening of the 9th of April, 1842. The newsboys rushed clamorously through the streets, selling hand over hand to the curious thousands who, wending their way up tow after the close of business, could not resist the inclination to buy "the last new novel" of the great English novelist at the unprecedentedly low price of twenty-five cents. That night, from five until ten o'clock, Wilson & Co sold over their counter all the copies which their nimble-fingered girls could stitch, and took in over $1600. The always demonstrative newsboys were riotous with delight, for many of them made from five to ten dollars that night; and three policemen found their hands full in keeping order among the crowd that besieged the office of publication. The whole sale of Wilson & Co's edition of this novel reached the number of between forty and fifty thousand.

This moment arguably helped set the course for cheap editions of all type of fiction for decades to come. Day proved that the country had the appetite for it, and competitors followed. But that competition did present Day with a new problem: due to the lack of copyright protection for foreign authors, it was a simple matter for any publisher to produce their own editions of popular works.

This lead to another clever move by Day: beginning with the September 3, 1842 issue of Brother Jonathan, he began importing numerous illustration plates from various foreign sources to use in Brother Jonathan. Text was relatively easy for any publisher to copy, but engravings were quite another matter.

Obadiah Oldbuck was a consequence of this move towards importing illustration plates as a hedge against competition. In this same issue, he made a bold prediction: "On the 14th, the extra issued from this establishment, will lead the way in a new style of publications in America."

He was talking about Brother Jonathan Extra No. 9, and of course, he was right.

While the floodgates certainly didn't open for a large quantity of comic books immediately — engraving was an extremely labor-intensive task at this time — Day's moves that September of 1842 had a couple of very important side-effects which had a major impact on comics over the course of the subsequent decades.

Due to the increased usage of engravings, Brother Jonathan became known as the first widely available and fully illustrated weekly in the United States. As engraving techniques became more cost effective and faster, this lead to a wave of illustrated weeklies such as Gleason's Pictorial Companion, Frank Leslie's Illustrated Weekly, Harper's Weekly, and many others. Harper's was the highest-circulation publication in the country, and it contained comic art and sequential comics on a regular basis. Comics were used in news reportage — to inform as well as entertain.

That's the true legacy of Brother Jonathan Extra No 9. Not more comic books, but more comics art in major publications everywhere, that everyone read. Comic art became a communication medium for the American audience as a result of that moment in time.

A book on the ancestry of the Day family later declared of Benjamin Day, "He was bred a printer."

This was true of his son as well. Benjamin Day Jr developed and patented the "Ben Day Dots" process, the technique used to print comic art and other illustration in color on cheap, mass-produced publications for the subsequent century.

Benjamin Henry Day played a key role in bringing the comic book and other popular entertainment to the masses in America. His son continued that legacy by developing the process that enabled much of that popular entertainment to be printed in color.