Posted in: Comics, Recent Updates | Tagged: Comics, david johnson, kickstarter, vintage comics

Edgar's Comics: How An Artist's Comic Collection Changed Comics Culture, And Became Worth $50 Million In The Process (Kickstarter Film)

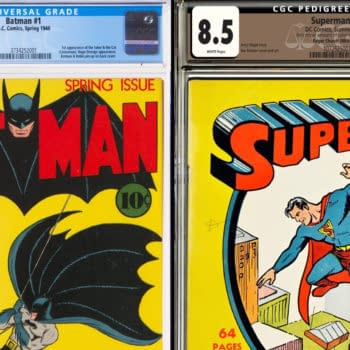

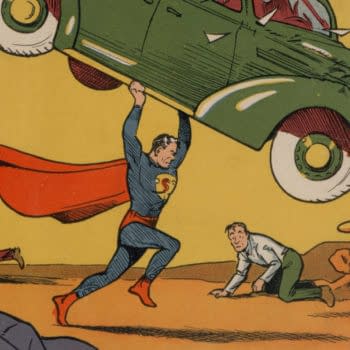

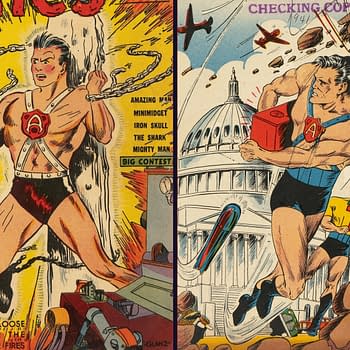

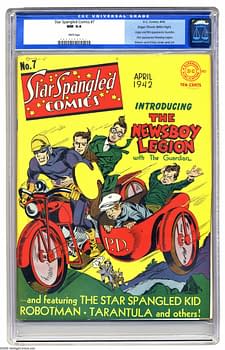

In 1977, comic book dealer Chuck Rozanski unearthed the most important comic book collection that the world will ever know. 18,000 comics from the late 1930s to the early 1950s — the earliest days of American comic books — in unimaginably high grade condition. All the important issues from comics' formative years are there –Action Comics #1, Detective Comics #27, Marvel Comics #1, Superman #1, and on and on — as well as most of the impossibly obscure ones. And many of them look like they were just purchased from a newsstand yesterday.

The details of this sequence of events are well known inside the vintage collecting community — the central story and numerous surrounding anecdotes have been elevated to the status of legend by many collectors. Not only are Edgar's comics highly sought-after, but the circumstances surrounding their accumulation, discovery, and sale are regularly discussed and dissected in microscopic detail. Comic book collectors have made the journey to Denver to see the house where Edgar Church lived and kept his comics in the basement. At least one or two collectors have even looked into buying the house. When Rozanski first began selling his find, the quality of it so stunned the collecting community that one fellow collector/dealer mortgaged his own house to attempt to buy as many of these comics as he could.

And after that? That's when things really got interesting.

Edgar's Comics: The Story

Rozanski bought the collection for around $1800 in 1977, and over three decades later, Edgar's comics have been bought and sold many times over, and disbursed into the hands of collectors around the world. Since then, the value of vintage comic books has exploded. Some estimates put the total value of the collection today well in excess of $50 million dollars. Edgar Church's copy of Action Comics #1 — considered by the few experts who have seen it as the best copy of Action #1 that exists today — is alone likely worth in the neighborhood of $3 million to $5 million, or more. No clear photograph or scan of the Edgar Church Action Comics #1 — the world's most valuable single comic and now in the hands of a private collector — exists anywhere on the internet.

If you think that sounds like a tale that combines the broad, newly-mainstream appeal of comics fandom and the sharp edge of one of its most intense collecting subcultures, with a liberal dose of treasure hunting (or more accurately in this case, treasure finding) thrown in, David Johnson agrees with you. Johnson is an aspiring Denver filmmaker who has dedicated himself to bringing this story to a wider audience on film. He's using Kickstarter to ask comic readers and collectors to help fund a film project examining the events surrounding the discovery of the Edgar Church collection.

More specifically, Johnson's Kickstarter film project, Edgar's Comics, uses this story as a lens of sorts, to view the pivotal moments when comics fandom began to transform from, as he puts it, "the primordial ooze of the 1960's", into the more cohesive comics culture that we know today. Not a documentary, the story Johnson is crafting develops a narrative around the discovery of Edgar's comics to put a human face on that transformation.

Talking to Johnson over the past couple weeks, he brings up films such as The Social Network and Moneyball to explain how he's bringing resonating themes of human interest to a story that is at its core about the complexities of a very focused subculture.

Those are good analogies, but when I think of the great untold dawn-of-comics-culture stories of the 1970s (and there are many), I keep coming back to something more along the lines of Cameron Crowe's Almost Famous. The aspiring rockers of the era from places like Alabama and Texas — staring out at you from album covers in threadbare t-shirts and jeans, hair unkempt, and looking a little dazed at the new-found attention — seem familiar. They remind me more than a little of comic dealers in convention floor photos from the same era. Schlepping equipment for gigs from show to show in the VW bus becomes packing up comics in a similar manner. In both cases, they're eventually heading towards the same place: bigger shows in California and New York, and the cosplaying glam of the coming decades.

Another matter I spoke to Johnson about at length is the reluctance of some of us who already know Edgar Church's tale to think of it as a story with broad appeal. As someone who has grown up with this story, and who owns books from the Church collection myself, I have to admit I was a little skeptical on this point too, at first. Those of us who grew up with it think of it as our story, or as something that only we can understand.

But Johnson is right. This story and others from the dawn of fandom are going to be told on increasingly larger stages, for increasingly mainstream audiences. It's almost as inevitable as the next big budget Marvel Studios or Warner Bros film.

What makes Johnson think he's the one to bring this story to the audience it deserves? It so happens that the Edgar Church story interests me a great deal, so I spoke to him at length on that very subject.

Edgar's Comics: The Movie

Bleeding Cool: What can you tell us in addition to what's on the Kickstarter page about the kind of work you do, and also what sort of artistic and technical experience you have that has lead you to undertake this project?

David Johnson: I'm a frustrated artist trapped in a corporate work-a-day life. Somehow, long ago, I, a liberal arts graduate, raised my hand in a meeting at one of my first "real" jobs; I mean that literally. From that point on, I've been on a path that's led me to become a project manager who specializes in very large, complex financial system implementations for telecom and securities firms. I've been a consultant for a number of years.

But, that's my vocation. My avocations are many, with photography being a lifelong passion. I'm not talking about simple happy snaps of the family picnic. I got pretty deep into it. I always used fully manual cameras and learned on film, prior to the digital revolution, which really does provide a solid technical foundation. Other interests are films, obviously. In general, I've always had a strong ability to visualise the abstract, which certainly comes in handy, given the existential nature of my work.

I first got into writing screenplays simply as a creative outlet, by unexpected motivation. My dearest aunt died, and I felt compelled to express myself at her memorial. My prepared eulogy seemed to touch a number people in her extended group of friends, all strangers to me, and they asked if I was a writer. At that same event, a cousin, whom I respect, urged me to "just write something". I couldn't think of any reason why I shouldn't be a writer. So, I started my first screenplay. Telling stories has become a part of my creative life.

It was about 10 years ago. It was a classic, public radio "driveway moment". You know, one of those I'm-so-glued-to-the-radio-I-

Reading some of your comments over on the Collector's Society board, I was struck by the fact that you're not someone I'd characterize as a hardcore golden age comic collector. How did you come to feel so strongly about telling this story?

I know my place in this crowd, and I wouldn't pretend to be something I'm not. I am not a paid up member of the tribe, but I am definitely a sympathetic observer. I collected newsstand issues for a couple of years. My first issues were in the early spring of 1980. I bought 167 comics during that time. I know this because I still have them, which is quite a feat, especially if you knew my mother and the number of times I moved.

I'm proud to say, I kept them in pretty nice shape, too. Nearly all of them are at least a 9.0 or better. I stumbled upon the Overstreet Guide at a bookstore, while visiting family in Chicago and that was a revelation to a 12 year old. I went to a couple of comic book conventions in Cincinnati, where I lived at the time. It was there that I bought an Iron Man #2 and an Avengers #10, which I was pretty jazzed about. As an adult I acquired a partial scattering of the first 50 issues of Amazing Spider-Man.

As for the Golden Age, I fantasized about owning the books. Even then, I think my true attraction to them were as historical artifacts. I was, and am, fascinated by what they reveal about the zeitgeist of their day. Today, I have 5 issues of Planet Comics, by Fiction House.

The bigger point to make is that it is not relevant that I am or am not a hardcore collector. In a way, it's better to have the objectivity provided by some detachment from the subject. If you're too close to something, you can lose perspective on what outsiders find interesting or curious. That's why we have Spock and Commander Data; they take us out of ourselves with their detachment. Same thing for Forrest Gump.

Writers do not have to be sentenced to death-row to write a prison movie. Writers do not have to be addicts to tell those stories. They don't have to be vampires, or queens or cowboys or soldiers to understand motivation.

My motivation and energy for telling the story of the Edgar Church / Mile High Collection is simply that it's a great story. The story's tagline is enough to grab one's attention. But, it actually works as a film because there is drama on multiple, interpersonal levels. A narrative film is not entertaining unless you care about the characters.

That goes to the very heart of the story I'm telling, and sums it perfectly. I examine every point you mention. 1977 is a pivotal moment. The discovery provides the element of drama, the high stakes, around which to build context, which provides the necessary dimension to tell an interesting story. I know it may sound far fetched, but there are mentions or vignettes about the economy, Nixon, Carter, Viet Nam, mobile phones, gothic architecture, the PC and the internet, and any number of changes looming, at that time.

I've seen some skepticism about this project among collectors who feel that Edgar's story is too niche to be of broad interest. How are you going to communicate what the collecting community values so much about this tale to a broader audience?

Let's be clear, this is a true story which also happens to have a potentially large, pre-installed audience. That's a good thing. But this is not a niche story, because it deals with universal human experience; thrilling opportunity, change, fear, jealousy, love, family, friendship, self-doubt, risk. I mention in my pitch that the film aspires to be The Social Network of the world of comics. That wonderful, successful movie, a best picture nominee, is superficially about the creation of website. Well, who would go to see that? Apparently, anyone who enjoys a great story about people making their way in the world. How about Moneyball? I don't care about baseball. But that's not really what the film is about. An audience wants to follow characters who navigate personal change.

I've had some general inquiries after the fact. The first hand accounts are available. For a narrative film, which is a dramatization, the real challenge is being faithful to the factual, key events, the pivots, and structuring those story beats in a way that sustains tempo and energy.

There are people who have studied this sequence of events in minute detail — who collect Edgar Church's art, visited The House, and even tried to buy it. Part of your task is to explain why this has so deeply fascinated some of us.

This is not a documentary. All narrative film must compromise with the constraints of the medium. Time is compressed, multiple characters are condensed into a single composite, dramatic scenarios are constructed for the purpose generating exposition of motive and context. As far as the modern day fascination are concerned, this is outside the timeframe in which my story takes place. But to your point about expressing collector passion, that is part of the story. That is done by inference and non-verbal expression. That is the job of the actor. Simply observing someone exhibit positive energy conveys passion. If you have to have a character say "I love comics because they are so…", that is less effective than letting your audience be drawn in by an affinity for the characters own appreciation.

Tell me a little more about the overall arc of this story as you are telling it — for example, does it begin during the golden age with Edgar buying his comics, and cover his own artistic endeavors?

The story centers around 1977, with multiple flashbacks, starting in 1960. Edgar is a presence in the film.

What direction does the story take immediately after the discovery?

The story focuses on the immediate aftermath of the discovery. Great opportunity brings change and the need to adapt to it. Chuck must make decisions on how to proceed. It is those decisions that lead to a series of changes that create friction within the community. Thirty-five years later, Chuck still gets biting criticism from some corners about the ethics of that day, and what "they" would have done if they were in the same position. Also, the economist in me looks at the concept of capitalism and consumer behavior. Through my interpretation of the available record, I present scenarios that are objective, yet also, sympathetic to Chuck. In a story arch, parallel to the discovery, Chuck grows as a person in his private life, as his relationship with his wife, Nanette, evolves from friendship to into romance. This is a guy who, at one point, was living in his car. That's fine as a young, mildly fanatical comic book junky. But, as people, we can't live that life forever. As a whole, I would say the story is split equally between life before the discovery and after.

Rozanski has been a pivotal and sometimes polarizing figure in the history of comics retailing. What will this project tell us about Rozanski and how this discovery effected his life?

The story cannot be told without Chuck. ALL narrative story telling is about intention meeting obstacle. This story works because it follows timeless themes. It's about a young man's ideals, the compromises that must be made, and sticking with one's convictions in the face of criticism. The importance of family. This story has nothing to do with finding a winning lottery ticket, then watching the lead character go shopping. That is boring, and wasn't what happened. There is all manner of subtext involved.

Chuck is a prolific writer. From his thrice weekly newsletter one can definitely get a sense that he is an outspoken personality with strong opinions. But I do not have a dog in the modern day fight. As an observer, I have no question that he loves the world of comics and has been a positive influence upon it. How can anyone argue otherwise?

Your underlying theme here has weight, but I'm going to nit-pick the "largest comic book dealer in the world" part a little since it's a bold statement — because it depends on how and when you define it. Many people familiar with the current industry would say that Midtown in NY is the largest direct market comic book retailer out there now — and at the other end of the spectrum you've got companies like Heritage and Comic Connect as the current heavyweights in sales of older comics, in terms of raw dollars. Certainly, Mile High is still one of the highest-volume comic book retailers out there, and at one time was probably the largest.

But more central to the point at hand: To what extent does the film focus on Rozanski building his business early on?

The film actually spends as much, or more, time on the earlier days of Mile High Comics, before the collection. This is the device that allows the audience to witness just how different things were back then. It better explains the who, what, why, and how, of the CULTURE, and why the collection was so pivotal. This is the perfect metaphor to the adage, 'Luck favors the prepared'. This is when everyone was hungry, metaphorically speaking. The hobby was still an adolescent and collectors were still trying to find themselves and each other. So, as far as Chuck's exploits after a quick peek into 1980, that is out of scope of this story.

I think it's important to stress that the tone of the film consciously avoids explicit moral judgment. I like stories that allow the sequence of events to unfold and then allow the reader to decide for themselves. There is the moral dilemma of the amount paid for the collection, and I examine that explicitly, to a degree. Regardless of how I treat it in the film, I'm certain that that single point will be the topic of conversation. It's simply too great a "what would you do?" scenario. Then, there is the overt conflict that arises by some corners, as Chuck asks for more multiples of guide. Chuck was getting actual hate mail and I make that strain apparent in both immediate and chronic ways the story. But "conflict" is not always overt. Rather it's often around the protagonist's journey of overcoming obstacles. "I've been told this can't be done. But I know that it can be. How do I solve this problem?". Again, the story arc makes clear that Chuck was not in for the quick buck. He wanted to change things. His out of the box thinking creates friction. It's surprising to hear, but in the story, a lot of people keep telling Chuck, "you can't do that". Then, there's the evolution in Chuck's private life, as he tries to attract his future wife Nanette. Chuck's personal history comes into play as well. This background demonstrates a lot of his character's motivation for why he did some of the things he does in the film.

This does bring up an important point: You've had no substantial contact with Rozanski about the project, though as you've noted there is quite a bit out there about the discovery and subsequent events on the public record. Does the historian in you wish you had more direct input from Rozanski, or are you content to draw a picture of events from the historical record?

I mentioned earlier that I would LOVE to have Chuck's direct input. I want to be clear that while this is not a documentary, (NO narrative screenplay is, I assure you) the events of the story and, I truly believe, the tone I take, are faithful to the public record. Chuck is a very expressive communicator. He is starkly open with his feelings and provides a very unusual amount of context in his descriptions; he's a great diarist. With that foundation available, the value that I am confident that I have added to the story is pulling off an unconventional structure and providing social context, outside Chuck's personal experience, that make the storyline engaging to an audience. I'm very proud of the story's tempo; the beats seem to fall in the right places.

In addition to Rozanski, can you give us some specifics as to what other figures from collecting history are in this story?

The center of gravity is clearly Chuck. At that time, especially, his social circle forms a network that allows the story to reach out into the comics landscape, on a level of personal experience. The interpersonal themes revolve around family, mentor and novice, love, jealousy and doubt.

In our phone conversation, you talked about the inclusion of comic dealers and other figures from collecting history in the film. Notably, you mentioned Burrell Rowe (A Houston, TX retailer who gave Rozanski funds to help purchase the collection in exchange for a portion of the comics from it), Jim Payne (a comic dealer pioneer whose A-1 Comics opened in Denver in 1967), and John Snyder (at one time a U.S. Under Secretary of Commerce, and major collector/dealer during this era). Can you elaborate on how each of these men — or analogs of them — figure into the film?

In serving the narrative structure of the screenplay, the characters of Jim, Burrell and John were constructed to act, in certain ways, analogous to the Dicken's ghosts of the past, present and future. One serves as a conduit into the past, to exposit the history of comic book collecting, as he mentors Chuck. One is there to explain the challenges that Chuck will face in the current reality of 1977. The other personifies the harsher criticism and conflict that Chuck will face.

In my story, which doesn't extend into that era, there is a scene that talks about the harsh trade terms that predominated at the time. Phil Seuling's name is dropped. The purpose of the scene is is to illustrate the tough time Chuck was having in "76/'77.

You've been developing this for some time.

The first draft took about 400 hours of actual sit-down writing, and maybe another 150 hours of research. It's simply staggering what's available. The ability to spend hours and hours listening to first person interviews of the leaders in the world of comics is invaluable. Chuck has spoken publicly and extensively about the discovery and his life. Those detailed interviews and lectures are openly available and are the foundation of the screenplay. But, my objective is not to make a biopic of Chuck or Edgar. The goal is to examine a concept, the history of the subculture, by following it through the personal experiences of a key player. I've introduced myself to Chuck. He was very gracious, warm and friendly. He said, at least, that he'd support the project but I think he's been extremely busy building out his new, enormous warehouse, on top of travelling more than 200 days a year. He has my number, and I hope he calls. Chuck, please call.

Would it be fair to say that a slice of what you're chronicling here is a business that was back-issue comics sales-driven that transformed itself into something more than that?

The story is first and foremost about a young man dealing with a lot of personal change. Both before the discovery, and after. This is not an ode to Chuck Rozanski, by any means. But, Chuck has an interesting personal history, and that history is so closely tied to the evolution of comic collecting. I mean, he started selling comics when he was 13? He founded a comic book club in a Colorado cow town. He paid his college tuition by trading comic books. Who does that? Telling the story of a subculture is a pretty abstract concept. Chuck and Mile High Comics are really used as a case study, to relate a broader concept, on a human scale. The story is really about collectors and the system they created for themselves.

Having had some time to digest everything that we've discussed about this project, one point jumps out at me that I think is going to be on the minds of everyone who is already familiar with this basic story: Your frame of reference contains a lot of Rozanski's part of the story but — from what we've discussed — doesn't seem to contain too much of Edgar Church's part of the story. You've chosen a specific, focused part of the story to tell on film and I think that's reasonable and prudent. But I also think many among the potential supporters of this project would want to see Edgar's own story told most of all. I'd like you to address that a little bit — what does this project do for the memory of the man who left us this legacy?

In conceptualizing the storyline, I struggled with how to incorporate Edgar. Clearly, he needs to be part of the journey, and I've done that in way that is faithful to the events that unfolded and does justice to his memory. The greatest challenge in writing this story, regardless, was it's structure. I'm trying to communicate, in an entertaining way, a story that hinges on a social and business idea; comic book collecting and the people who love it. My hands were tied by the paucity of information that's available about Edgar. Simply put, all we know about him are bullet points: Born back east in 1888, married twice, two children, artist, various addresses recorded in the Denver area. Died, several months after the sale of his comics. There just isn't much to build a story around.What I beleive that hard core Golden Age collectors want is the opportunity to see Edgar in the "flesh" and, ultimately, to "thank" him for his legacy to the those who came after. That was my instinct, at least. I actually kicked around a scenario where Chuck, after learning that Edgar was still alive, visited him in the nursing home, to allow the generations to pass the baton. But, I decided that, while cathartic, it was simply too great a license to take. His children knew him, but there just isn't much in the public record. Doris and Richard take on important roles in the film, and through them we get a glimpse of Edgar.

Without giving away too much of my solution, I can tell you that we see Edgar on screen; in the beginning, middle and end of the story. We see him building his collection. We watch him at his creative process. A key arch in the film, and I state this explicitly in the trailer, is that learning about Edgar is a major objective int he film. The audience will come away knowing we do know about him.

As for Chuck's frame of reference, that's all we have. There are comments about some details that have changed over the years but, Chuck was there; Doris, Richard, Chuck and the realtor. There was the lawsuit brought by Doris and Richard but the court ruled in Chuck's favor. Based on that indisputable fact, it is reasonable that Chuck's description is accurate. Without re-litigating that action, which, again, is outside the scope of my story, I do acknowledge that lawsuit.

As for Edgar's legacy, it's important to acknowledge that because of the extra efforts taken by Chuck that day, and episodes later on, AFTER all the comic books were in his possession, Chuck is the one responsible for saving the creative legacy of Edgar Church.

I have a historical analogy; there's an inaccurate story that's passionately believed by some. The reason that the Sphinx in Egypt is missing it's nose is because Napolean ordered it defaced, because he worried the West's rediscovery of the grandeur that was Ancient Egypt, would damage European self-confidence. What adherents of this story fail to reconcile is that Napolean filled the Louvre with the wonders of that lost world, which created the field of Egyptology. Some criticisms, from some corners, do not seem rational to me.

How would comic book fandom be different today if Edgar's comics had never been found?

Thirty-five years have passed since the discovery. It is not that the world of comics, today, would be a shadow of itself without it. Progress is inexorable. Rather, it's how the discovery set in motion, at that point and not some later date, the motivation for collectors and stakeholders on the business end, to come to terms with the needed change that Edgar's Comics engendered. There was an organic confluence of events. Not everything is a linear progression; cause and effect. Some things happened autonomously and concurrently. Like Comicon or like the explosion of mass-media driven pop-culture, and Hollywood's search for content that comic books offered. The singular event of Star Wars, that same year, that crossed all demographics. The technology revolution gave the hobby a needed kick that sustains it, today. The point being that, fi this is where we are today, how did we get here? What came before? How did it work before? I try to answer some of these questions in Edgar's Comics.

Edgar's Comics: The Script

Discussing this project with Johnson, it became clear that he has a very specific vision for the story he wants to tell and how he intends to tell it. I asked him to convey that vision for Bleeding Cool readers with an excerpt from the script, and below is a key scene from the proposed movie — the removal of the collection from Edgar Church's house, set against a backdrop of changing times for the comic book industry.

Edgar's Comics is a Kickstarter project with a goal of raising $68,000 by January 29 to fund the film. If successful, Johnson hopes to have the film ready by the time of San Diego Comic Con next year, as well as film festivals such as Sundance.

Update: Johnson informs me that voting for the project to be IndieWire's Project of the Week (before Monday, Dec 26) will heighten its visibility considerably within development circles.