Posted in: Comics, Vintage Paper | Tagged: Promise Collection, superman

The Promise Collection 1942/1943: The Comics Committee

"The value of Time Magazine as a purveyor of news, or of Superman Comics as a journal of entertainment will not be matched against each other with a car of paper going to the winner," Norbert A. McKenna, Chief of the Paper and Pulp Branch of the Office of Production Management told Writer's Digest in early January 1942. Such a statement would likely have been welcome news to the growing legion of young comic book fans, like the boy who assembled the Promise Collection — but the Writer's Digest piece would soon take a sobering turn. While maintaining at the outset of the exchange that "The Government does not intend, at this time, to ration paper", McKenna immediately contradicted himself and went on to describe in great detail how paper would likely be rationed. Over industry protests the next month, McKenna devised a wood pulp allocation program in March 1942 which was implemented that May. General Preference Order M-93 placed the entire pulp industry under an allocation system governed by the War Production Board, which required pulp consumers to file their orders with producers in a prescribed way, with the WPB then directing deliveries to those consumers after review.

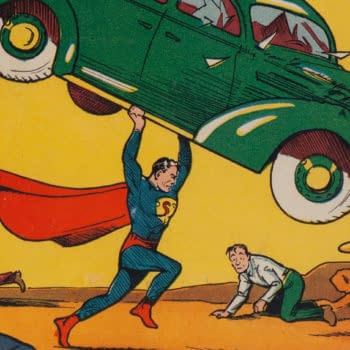

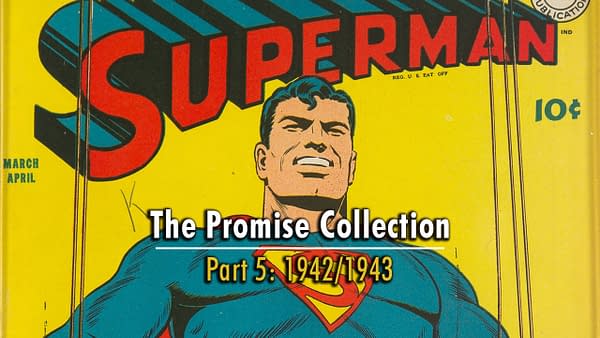

Fortunately for the booming comic book industry, Norbert McKenna was a much better administrator than he was a government spokesman, and wood pulp supplies remained more than adequate to meet demand throughout 1942 and into early 1943. Writer's Digest had predicted in January 1942 that they expected that "the usual number of new magazines will be launched", and this is certainly reflected in the number of new #1 issues present in the Promise Collection through the mid/late 1942 to early 1943 period. Boy Commandos #1, Captain Marvel Jr #1, Clue Comics #1, Comic Cavalcade #1 and Miss Fury #1 are among the new series launches in the collection from this era. The collection would add a few other important regular series to its historical pull list during this time, such as Wonder Woman starting with #3, and at long last… Superman starting with #20. But while the young fan who assembled the Promise Collection would not see some of the direct impact of paper rationing until later in 1943 (for example, when Sub-Mariner Comics #12 was eight pages shorter and about a half-inch more narrow than Sub-Mariner Comics #11), some of the other effects of the rise of governmental control over industry would come far sooner.

Welcome to Part 5 of the Promise Collection series, which is meant to serve as liner notes of sorts for the comic books in the collection. The Promise Collection is a set of nearly 5,000 comic books, 95% of which are blisteringly high grade, that were published from 1939 to 1952 and purchased by one young comic book fan. The name of the Promise Collection was inspired by the reason that it was saved and kept in such amazing condition since that time. An avid comic book fan named Junie and his older brother Robert went to war in Korea. Robert Promised Junie that he would take care of his brother's beloved comic book collection should anything happen to him. Junie was killed during the Korean War, and Robert kept his promise. There are more details about that background in a previous post regarding this incredible collection of comic books. And over the course of a few dozen articles in this new series of posts, we will also be revealing the complete listing of the collection. You can always catch up with posts about this collection at this link, which will become a hub of sorts regarding these comic books over time.

Promise Collection and the Comics Committee

Another series that Junie would take a look at for the first time during this period was Pep Comics, which featured the patriotic character the Shield. The first issues of the series in the Promise Collection, Pep Comics #29 and Pep Comics #30 feature a fascinating two-part story in which the Shield loses his superpowers and then fails to regain them. The story appears to be a calculated editorial move to demonstrate to readers that it doesn't take someone with superpowers to fight for America — ordinary people can do so as well. As he explains in an "emergency announcement" in Pep Comics #29, "Whether or not I ever regain those powers, it's still an all-out battle against the enemies of the U.S., the cutthroats who are battling against our democracy… I'd be a pretty poor American to lay down on the job now, what with all those soldier boys fighting on the front." A later special bulletin doubled down on this by saying, "The loss of my super-powers is a thing of the past… like the bombing of Pearl Harbor and the loss of Bataan. And just as American soldiers are inspired to stronger battle by their losses, instead of being discouraged by them — my fight is going to be stronger and stronger until, along with our fighting men, I'll crash through to victory."

In Part 1 of this Promise Collection series, we noted how the Shield was in part inspired by the events of World War I — his origin includes a reference to one of the most infamous acts of sabotage from that prior war, the Black Tom explosion. The subsequent chain of events would likewise loom large over the future of the industry: Congress would pass the Espionage Act the next year, which was then used for the first time against cartoonists when the U.S. Post office banned the magazine The Masses from mailing an issue due to what it called anti-war cartoons. Cartoonists and staff of the magazine were later put on trial, and while the government failed to convict The Masses group even after trying twice, the weight of the government's efforts effectively ended the magazine in 1917.

These events would nudge three figures from The Masses' moment in history along a path towards a role of significant influence over the comic book industry of the World War II era and beyond. Judge Learned Hand made his first decision involving a comics-related periodical in Masses Publishing Co. v Patten ruling in favor of The Masses, though this was later overturned. In the wake of The Masses matter, President Woodrow Wilson's Committee on Public Information, a producer of national propaganda via diverse media, launched the Bureau of Cartoons. The Bureau of Cartoons began in early 1918 headed by a man named George Hecht, who lead the attempt to get the nation's cartoonists working in support of the war. And in 1926, writer Rex Stout helped launch a successor to The Masses called The New Masses. The Bureau of Cartoons' George Hecht would later become the founder and publisher of Parents Magazine, which he used as a platform to attack the comic book industry, while also publishing what he considered a superior alternative. Judge Learned Hand would go on to preside over both DC Comics v Bruns (the Superman vs Wonderman lawsuit) and DC Comics v Fawcett Publications (the Superman vs Captain Marvel lawsuit). And Rex Stout, who became best known for his detective fiction character Nero Wolfe, would become the chairman of the Office of War Information's Writers' War Board.

"On paper, the Writers' War Board (WWB) was an independent organization staffed by volunteers committed to the creation of anti-fascist, pro-American culture," notes historian Paul Hirch. "In reality, the WWB received funding and direction from a federal agency called the Office of War Information (OWI). The WWB allowed the government to create unofficial propaganda for consumption by civilians and servicemen. Shielded by its veneer of independence, the WWB wove propaganda into popular culture to fuel a hatred of fascism, using language and images not available to propagandists openly affiliated with the government. Within the WWB there was a Comics Committee that created comic book characters and story ideas that were then passed to cooperating publishers… A publisher in good standing that printed WWB-sanctioned stories might receive access to additional wood pulp, and sell more comic books."

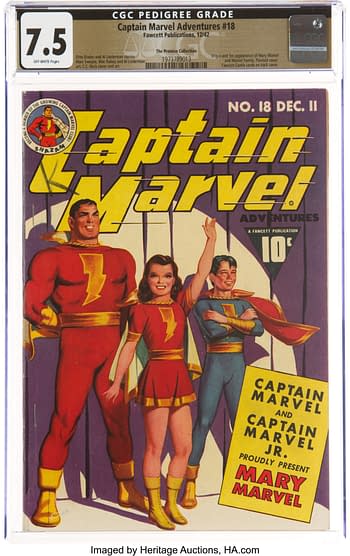

Beginning in early 1943, the WWB extended its purview specifically into comic books with the creation of the Comics Committee, because WWB members concluded that "the core traits of the comic book form — its broad popularity, comprehensibility, emphasis on raw emotion, and distinct lack of subtlety — marked comic books as a potentially useful delivery system for propaganda." Several major comic book publishers worked with the WWB on a deep level — submitting story drafts, creating characters, and even developing specific story and feature ideas under the guidance of the WWB. Fawcett publication was among the publishers who worked with the WWB and other government agencies.

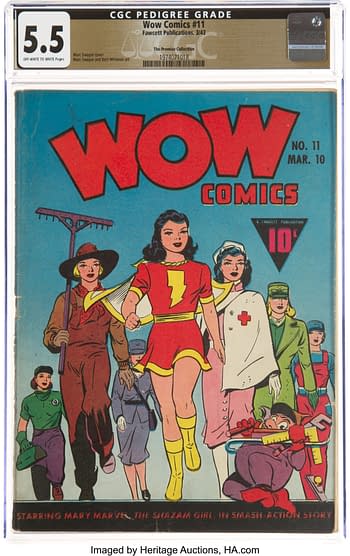

The Promise Collection's run of Fawcett's Wow Comics begins with Wow Comics #9, the debut of Mary Marvel as the feature of her own series after first appearing in Captain Marvel Adventures #18. Wow Comics #11 contains a clear-cut example of the likely influence of the WWB on a comic book story. The cover of this issue is a typically gorgeous piece of work by Mary Marvel co-creator Marc Swayze of Mary leading a number of women to work in professions like farming, factory work, nursing, and mechanical work among others. In the story, Mary Batson rebels against the notion of "her proper place in society" by entering the workforce. She is hired as a telegram messenger, and her boss explains that women are entering the workforce in greater numbers in the U.S. as men go off to war. It's relatively easy to trace the origin of Mary Marvel's storyline in this issue. A few months prior to the debut of this issue, the WWB's Magazine War Guide included the following:

WOMAN POWER IN THE WAR — the subject everybody is talking about — is a "natural" for magazine coverage. In dealing with it, however, it is advisable for editors to take into consideration the following policy decision of the War Manpower Comission:

Employment of women in seemingly non-war production jobs, such as railroads, buses, street cars, retail stores dealing with essentials, etc., should be viewed as "war work" inasmuch as women must take the places of men who have been called into military war production service.

As anyone with a serious interest in the comic books of this period will have perceived, other aspects of the WWB's contributions to comics were of a far different nature than the above example of promoting women in the workforce. In cooperation with the WWB, comic book publishers "constructed a justification for race-based hatred of America's foreign enemies." Returning to the Magazine War Guide, we can find stark examples of the WWB's suggestions to "portray the nature of our Eastern enemies to the American people." WWB Chairman Rex Stout exemplified the mindset of the time which led to such portrayals with a famous 1943 essay in the New York Times called We Shall Hate, or We Shall Fail, noting "If we do not hate the Germans now, we shall fail in our effort to establish a lasting peace."

Iron Jaw and the Man of Tomorrow

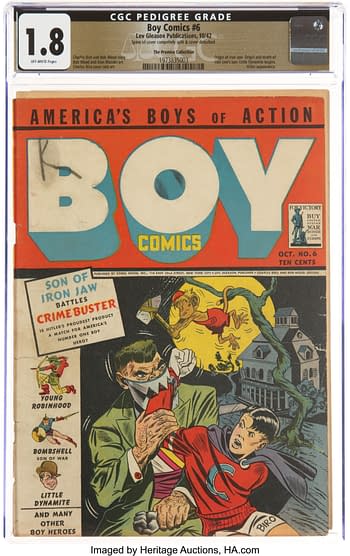

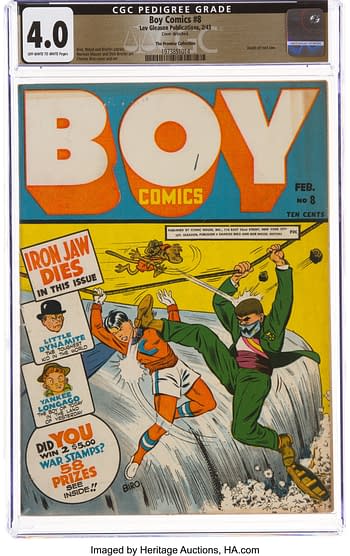

In part 3 of this series, we noted that the Promise Collection contains one of the most infamous wartime propaganda comic books of the era with Daredevil Comics #1, better known as "Daredevil Battles Hitler" — a release from publisher Lev Gleason which certainly aligns with the tactics that Rex Stout explained. And while Gleason's Boy Comics #6 doesn't garner the attention of Daredevil Comics #1, in some ways it should. In this issue, writer/artist Charles Biro turned the character Iron Jaw from a fairly typical comic book villain into an extremely hateable wartime enemy. While the character had first appeared in Boy Comics #3, his origin as told in Boy Comics #6 is a doozy. It's explained in the story that the man who would become Iron Jaw, Sergeant von Schmidt, had befriended young Adolf Hitler on the Belgian front during WWI. In battle on the front line, Hitler shoots a superior officer who had opposed him. Thinking that Sergeant von Schmidt had been involved in the act as well, the officer tosses a grenade at him — blowing his jaw off in gruesome fashion on the page. Years later, Iron Jaw resumes his relationship with his old friend Hitler, who has by then risen to power in Germany. Iron Jaw has a son by this time as well, who also rises within the Nazi party and is considered the strongest youth in Germany — in Hitler's words the "perfect Man of Tomorrow." With Iron Jaw presumed dead at this time due to the events of Boy Comics #4, it soon transpires that Hitler tells Iron Jaw's son that the hero Crimebuster killed him, and sends the son to America to seek revenge. But Crimebuster convinces the boy that Hitler is a liar — leading to a shocking ending with Iron Jaw returning to murder his own son in close combat. As Iron Jaw later explains, "I had to kill him because he was bitten by a mad disease called Americanism!"

But not every comic book of the period contains such heavy war-era themes, even in 1943. About three months after Boy Comics had Hitler using the phrase "Man of Tomorrow", the real Man of Tomorrow seemingly returned the favor (or insult, as the case may be) with the lead story by Jerry Siegel and artist Ed Dobrotka casting Superman's foe for the issue as a run of the mill gangster named Ironjaw who is easily defeated by our hero. Despite Superman #20's war-themed cover, the story is a wonderfully light-hearted tale of Lois Lane accidentally exposing Superman's real identity of Clark Kent with what she thinks is a gag.

The comics industry itself had ample reason to be upbeat from time to time through this period, even as the war progressed. Like the rest of the publishing business in America, comics had felt little print-production impact from the War Production Board's control over wood pulp and other industries. But this was about to change. In spring of 1943, the wood pulp situation became critical, and additional measures were put into effect which empowered the WPB to dictate the end uses for the allocated pulp, an action which brought America's paper production and usage under full government control. The impact of this turn of events would be unmistakable to the young fan who assembled the Promise Collection in the months ahead.

| Comic Title | Issue # | CGC Grade / Auction Links | Prices Realized |

|---|---|---|---|

| All Hero Comics | 1 | ||

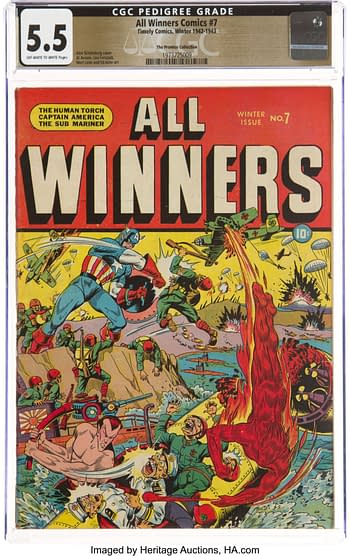

| All-Winners Comics | 7 | All Winners Comics #7 CGC FN- 5.5 Off-white to white pages. | $9,600.00 |

| America's Greatest Comics | 4 | ||

| America's Greatest Comics | 5 | ||

| America's Greatest Comics | 6 | ||

| Batman (1940) | 12 | ||

| Batman (1940) | 13 | ||

| Batman (1940) | 14 | ||

| Batman (1940) | 15 | ||

| Boy Comics | 6 | Boy Comics #6 CGC GD- 1.8 Off-white pages | |

| Boy Comics | 8 | Boy Comics #8 CGC VG 4.0 Off-white to white pages | $384.00 |

| Boy Commandos | 1 | ||

| Bulletman | 7 | ||

| Bulletman | 8 | ||

| Captain America Comics | 17 | ||

| Captain America Comics | 18 | ||

| Captain America Comics | 19 | ||

| Captain America Comics | 20 | ||

| Captain America Comics | 21 | ||

| Captain America Comics | 22 | ||

| Captain America Comics | 23 | ||

| Captain America Comics | 24 | ||

| Captain Marvel Jr. | 1 | ||

| Captain Marvel Jr. | 2 | ||

| Captain Marvel Jr. | 3 | ||

| Captain Marvel Jr. | 4 | ||

| Captain Marvel Jr. | 5 | ||

| Captain Marvel Adventures | 14 | ||

| Captain Marvel Adventures | 15 | ||

| Captain Marvel Adventures | 16 | ||

| Captain Marvel Adventures | 17 | ||

| Captain Marvel Adventures | 18 | Captain Marvel Adventures #18 CGC VF- 7.5 Off-white pages | |

| Captain Marvel Adventures | 19 | ||

| Captain Marvel Adventures | 20 | ||

| Captain Marvel Adventures | 21 | ||

| Captain Marvel Adventures | 22 | ||

| Clue Comics | 1 | ||

| Clue Comics | 2 | ||

| Clue Comics | 3 | ||

| Comic Cavalcade | 1 | ||

| Daredevil Comics (1941) | 13 | ||

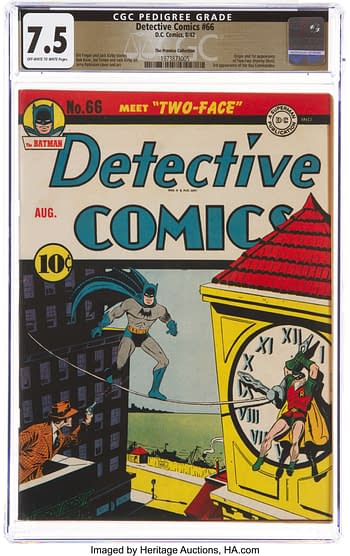

| Detective Comics | 66 | Detective Comics #66 CGC VF- 7.5 Off-white to white pages | |

| Detective Comics | 67 | ||

| Detective Comics | 68 | ||

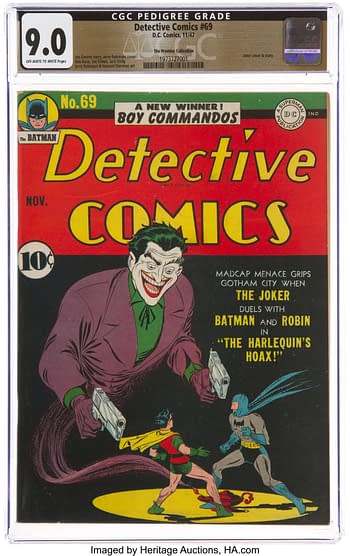

| Detective Comics | 69 | Detective Comics #69 CGC VF/NM 9.0 Off-white to white pages | $126,000.00 |

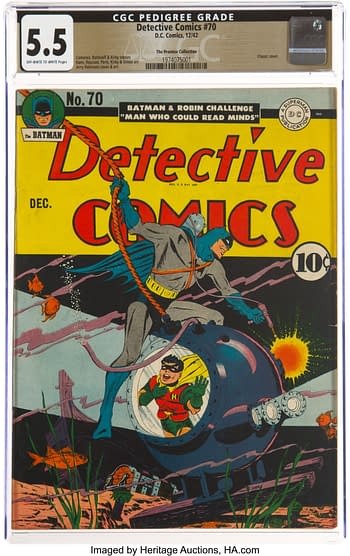

| Detective Comics | 70 | Detective Comics #70 CGC FN- 5.5 Off-white to white pages | $2,760.00 |

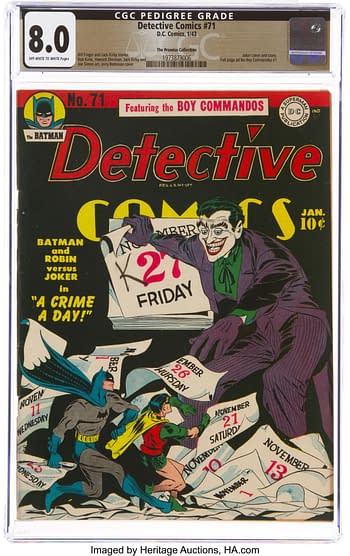

| Detective Comics | 71 | Detective Comics #71 CGC VF 8.0 Off-white to white pages | |

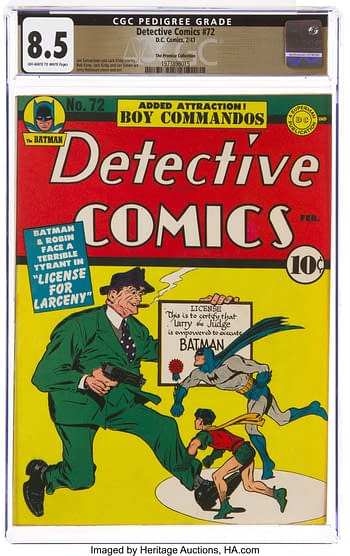

| Detective Comics | 72 | Detective Comics #72 CGC VF+ 8.5 Off-white to white pages | |

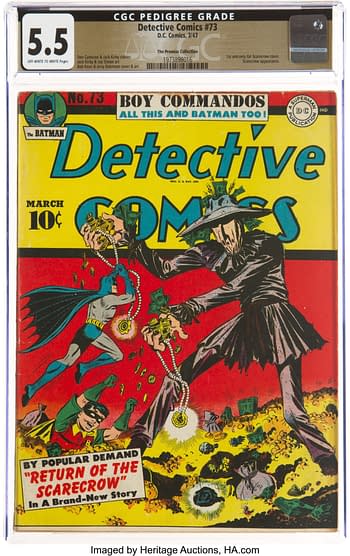

| Detective Comics | 73 | Detective Comics #73 CGC FN- 5.5 Off-white to white pages | |

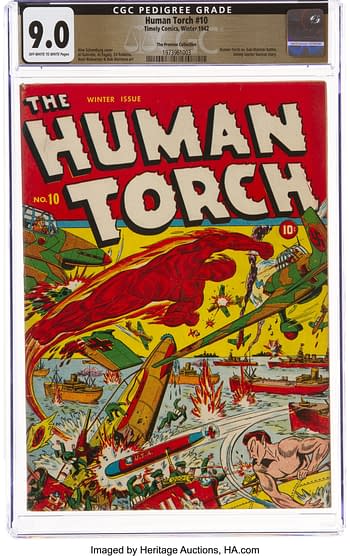

| Human Torch | 10 | The Human Torch #10 CGC VF/NM 9.0 Off-white to white pages | |

| Joe Palooka | 1 | ||

| Joe Palooka | 2 | ||

| Jungle Girl (1942) | 1 | ||

| Master Comics | 34 | ||

| Master Comics | 36 | ||

| Miss Fury | 1 | ||

| Pep Comics | 30 | ||

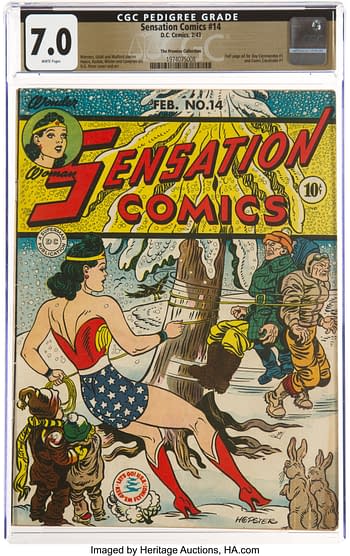

| Sensation Comics | 14 | Sensation Comics #14 CGC FN/VF 7.0 White pages | $3,000.00 |

| Superman (1939) | 20 | ||

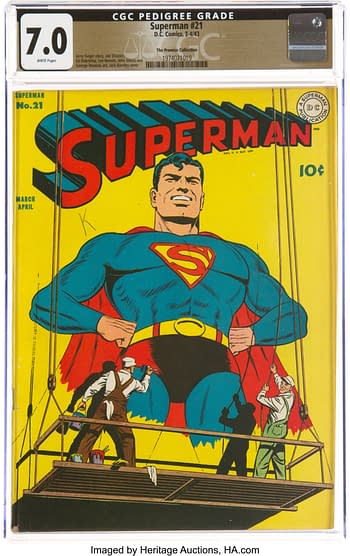

| Superman (1939) | 21 | Superman #21 CGC FN/VF 7.0 White pages | $3,600.00 |

| Tough Kid Squad | 1 | ||

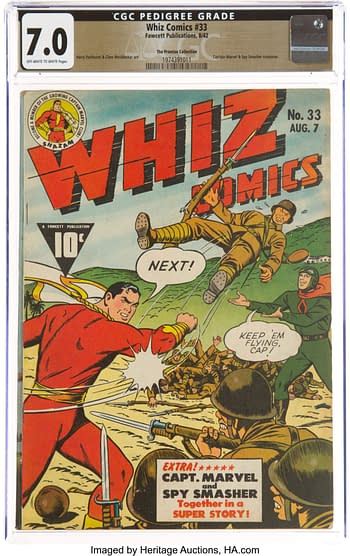

| Whiz Comics | 33 | Whiz Comics #33 CGC FN/VF 7.0 Off-white to white pages | $840.00 |

| Whiz Comics | 34 | ||

| Whiz Comics | 35 | ||

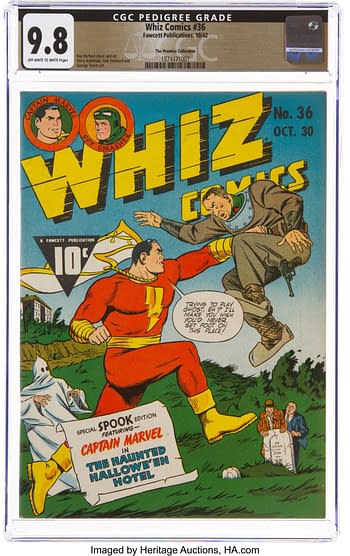

| Whiz Comics | 36 | Whiz Comics #36 CGC NM/MT 9.8 Off-white to white pages | |

| Whiz Comics | 37 | ||

| Whiz Comics | 38 | ||

| Whiz Comics | 39 | ||

| Whiz Comics | 40 | ||

| Wonder Woman (1942) | 3 | ||

| World's Finest Comics | 7 | ||

| World's Finest Comics | 8 | ||

| Wow Comics | 9 | ||

| Wow Comics | 10 | ||

| Wow Comics | 11 | Wow Comics #11 CGC FN- 5.5 Off-white to white pages | $960.00 |

| Young Allies | 5 | ||

| Young Allies | 6 |

- All Winners Comics #7 The Promise Collection Pedigree (Timely, 1942) CGC FN- 5.5 Off-white to white pages

- Boy Comics #6 The Promise Collection Pedigree (Lev Gleason, 1942) CGC GD- 1.8 Off-white pages

- Boy Comics #8 The Promise Collection Pedigree (Lev Gleason, 1943) CGC VG 4.0 Off-white to white pages.

- Captain Marvel Adventures #18 The Promise Collection Pedigree (Fawcett Publications, 1942) CGC VF- 7.5 Off-white pages

- Detective Comics #66 The Promise Collection Pedigree (DC, 1942) CGC VF- 7.5 Off-white to white pages

- Detective Comics #69 The Promise Collection Pedigree (DC, 1942) CGC VF/NM 9.0 Off-white to white pages

- Detective Comics #70 The Promise Collection Pedigree (DC, 1942) CGC FN- 5.5 Off-white to white pages

- Detective Comics #71 The Promise Collection Pedigree (DC, 1943) CGC VF 8.0 Off-white to white pages.

- Detective Comics #72 The Promise Collection Pedigree (DC, 1943) CGC VF+ 8.5 Off-white to white pages.

- Detective Comics #73 The Promise Collection Pedigree (DC, 1943) CGC FN- 5.5 Off-white to white pages.

- The Human Torch #10 The Promise Collection Pedigree (Timely, 1942) CGC VF/NM 9.0 Off-white to white pages

- Sensation Comics #14 The Promise Collection Pedigree (DC, 1943) CGC FN/VF 7.0 White pages.

- Superman #21 The Promise Collection Pedigree (DC, 1943) CGC FN/VF 7.0 White pages.

- Whiz Comics #33 The Promise Collection Pedigree (Fawcett Publications, 1942) CGC FN/VF 7.0 Off-white to white pages

- Whiz Comics #36 The Promise Collection Pedigree (Fawcett Publications, 1942) CGC NM/MT 9.8 Off-white to white pages

- Wow Comics #11 The Promise Collection Pedigree (Fawcett Publications, 1943) CGC FN- 5.5 Off-white to white pages.