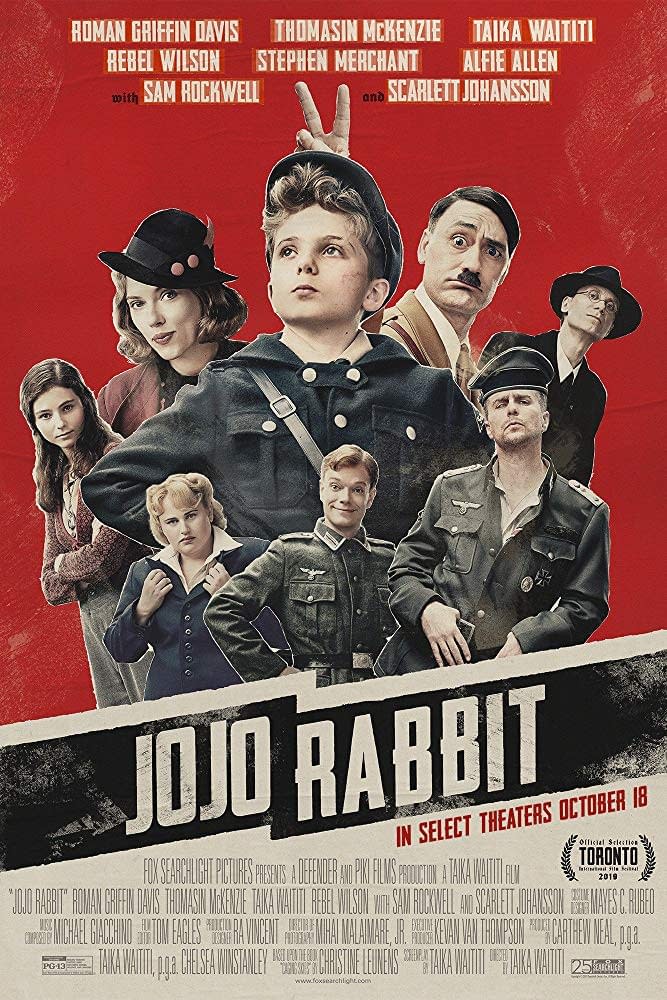

Posted in: Movies | Tagged: Jojo Rabbit, movies, taika waititi

What "Jojo Rabbit" Has to Say About Redemption (Spoilers)

In my final year of college, my long-time Hebrew professor, a very guarded woman when it came to her personal life, came into class one morning and told the story about how Nazis ruined her family. She told us about her family members who had been in concentration camps and the family's eventual run to South America to flee the horrors. She shared this as a preface the news she had to share: she'd been told that any of her students who were interested would be welcome to attend a scholars conference about the Holocaust being held on campus. She planned to attend herself, so she canceled classes for the week and gave anybody who would commit to attending some of the sessions credit for having been in class. After I attended the first session, I decided to take the week off of the rest of my classes as well and attend full time.

There was a reverence about the event, a sense that there was important work being done. Among the week's worth of sessions that I attended, each more heartbreaking than the last, one stands out clearly; a session simply titled "The Liberators."

In it, a panel of soldiers who had been there when the camps were first liberated told their stories. They were moving. They were violent and horrific. They were all delivered in hushed tones. One man stood up and began with unforgettable words.

"I don't want to be here."

He went on to talk about the fact that liberating a concentration camp had caused him to compartmentalize all that he'd seen, spending his entire life doing everything possible to not think about it. His wife and children knew that he'd served in the military and wondered why he couldn't talk about it. It took his adult daughter to convince him to participate, citing the importance of sharing his eyewitness to the repugnant things he'd seen in the camps. "This is the first and last time I will talk about these things," he said.

I recall a couple of people – ostensibly an audience mostly made up of those who study the Holocaust and the horrors involved for a living – standing up and leaving. Something about the flat affect of this man who had been tortured his entire by the memories of what he'd seen. And having seen them, he felt a sense of duty to relate the full scope of the horror. But he didn't want to do it. He was haunted by it.

I heard the eyewitness accounts of dozens of survivors of the Holocaust during the course of the conference. I heard the eyewitness accounts of liberators. I'd studied about them in history class but there is a different reality to listening to a man in his final years of life describing horrific scenes for the first time in his life that he'd spent the decades pushing away, refusing to talk, wanting nothing more than to pretend he hadn't seen what he had.

Still, I was glad I'd taken the time to attend. The conference offered a more concrete understanding of why scholarship on the subject was necessary to provide the knowledge that would help the world to avoid such horrors in the future. It also began a six-month bout of depression that was tenacious and unrelenting.

Warning for minor spoilers for Jojo Rabbit.

So there's my bias going into to Taika Waititi's latest movie Jojo Rabbit. In some ways, a story about the impact of white supremacy and Nazi ideology is something I'm a sucker audience for, having heard about those impacts from those who were there and saw them personally. But there's also a black maw that surrounds the subject for me; I've heard undeniable stories that shade any movie about the subject making it much darker than a movie about some other topic.

Jojo Rabbit is about the journey of Johannes Betzler, a 10-year-old German boy who loves being a Nazi. He's excited to attend Hitler Youth Camp where he'll learn important Nazi skills including how to kill casually and proudly, how to throw a hand grenade, and how to shoot a rifle. And, most of all, he'll learn about Jews, a constant source of fascination and concern for Jojo. His Nazi leaders will answer his questions about Jews as will his special imaginary friend, Adolf Hitler.

Portraying the Nazi experience through the sense of wonder of a 10-year-old is a brilliant and slightly perverse take on the WWII film. Jojo is a kind, imaginative boy whose childhood is protected by his mother (Scarlett Johanssen) in a desperate, almost manic manner. He lives in a Germany that is sketched in all the colors of his own optimism. Despite the film taking place in the waning days of the war, a period when Germany was clearly on its heels, Jojo is excited to participate in the glorious war machine of the Fatherland and really loves his country. His kindness and essential innocence are reflected in his imaginary friend Hitler (Taika Waititi), who is as sunny and encouraging as Jojo himself.

Playing Hitler as silly has a long history in pop culture. Charlie Chaplin famously did it in The Great Dictator in 1940 and ended his movie with a straight-down-the-barrel plea for sanity from the world that is still incredibly moving. Both Warner Bros. and Disney have cartoons lampooning him and the Nazi Party. Spike Jones and His City Slickers performed a rude title song for the Academy Award-winning Disney movie Der Fuehrer's Face.

After the war, making Hitler silly was a powerful coping device. Mel Brooks' 1967 movie The Producers features a pair of Broadway producers looking to stage a surefire flop as a money-making scheme; they select a script titled Springtime for Hitler: A Gay Romp with Adolf and Eva at Berchtesgaden as their guaranteed failure. Its signature production number "Springtime for Hitler" is as beautiful and hilarious as it is audacious. Red Dwarf and Monty Python's Flying Circus each took a turn at making Hitler the object of ridicule as well.

Taika's take on the character of Hitler is nothing short of ebullient. Taika's natural charm, which is already considerable, is turned to 11 for this role. Jojo's mental version of Hitler is a charismatic cheerleader, a voice of confirmation for his life decisions, and occasionally a momentary voice of doubt, reticence, and even darker thoughts, all wrapped up in a Nazi uniform. In short, Taika's Hitler is Jojo himself.

After a run-in with a hand grenade at Hitler Youth Camp leaves him limping and scarred, Jojo spends time working with the Hitler Youth office near his home. One day he discovers that his mother has been harboring a Jew in the wall of his dead sister's room. Elsa first threatens and then befriends Jojo. He is fascinated to find a real-live Jew living so close. He asks questions that have as their foundation the essential vermin nature of Jews. As their friendship grows, Jojo begins to question that foundation and, as the war does what it must do, take and take and take away from those involved, he eventually questions his Nazism. "You're not a Nazi, Jojo. You're a 10-year-old kid who likes dressing up in a funny uniform and wants to be part of the club."

The twist that Waititi offers in Jojo Rabbit that is missing from all of the rest of the silly depictions of Hitler and Nazis is a path to redemption. That's no surprise: his film was inspired by seeing a resurgence in real-life, in-the-flesh white supremacists in the U.S. and elsewhere. It's a savvy and gentle choice, in the absence of death camps and invasions of Poland (so far), to depict not only the horrors that naturally flow from racial supremacist rhetoric but to humanize those who espouse it.

One can become a Nazi while still being a kind, caring human being, Jojo demonstrates. The movie shows the journey of a good boy from somebody who loves his mother but pledges fealty to the Fuhrer to an adolescent who recognizes cruelty and the wages of war and turns his back on it.

This novel part of this Nazi story – where a lost boy sees human suffering and decides to leave his club, his uniform, and his racial stereotypes and prejudices behind him to become a happier and better person – is instructive for the current crop of Nazis who find themselves with even a single question about their path. It's a nuanced, gentle outlook that reflects Waititi himself, whose wicked sense of humor can be seen in previous films What We Do in the Shadows and Hunt for the Wilderpeople. Beneath the humor is an essential humanity, a thoughtful consideration of both the natural consequences of white supremacy being on the rise but also a realization that some of those swept up in that rise are there for less venal, more redeemable reasons.

Taika says, through his 10-year-old Jojo, that it's never too late to stop being a Nazi. It's never too late to regain your humanity by making up for the evil you've supported, kick it straight out the window, and dance with a girl.