Posted in: Comics | Tagged:

Marvel's Age Of X-Man and a Brief History Of Utopian/Dystopian Sexuality (Spoilers)

Utopia is a work of fiction and socio-political satire by Thomas More, published in 1516, entirely in Latin. You'll see a copy on V's bookshelf. The book depicts a fictional island society and its religious, social, and political customs. And it created a genre of dystopian fiction.

In Utopia, there is no private property, locks were forbidden, and houses are rotated around the population. Everyone must work as a farmer for two years criminals must serve as slaves for households. Utopia has free hospitals, euthanasia is permitted, and the law is so simple that all lawyers were banned.

In Utopia, women are not allowed to marry until they are 18, at a time when most women married at the age of around 14. Divorce was now legal. Priests are allowed to marry, but premarital sex is punished by a lifetime of enforced celibacy–though husbands and wives are allowed to inspect each other's naked bodies before they marry. Adultery is punished by enslavement.

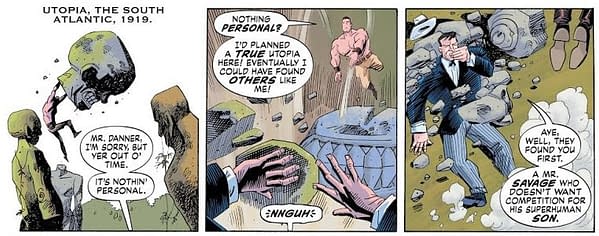

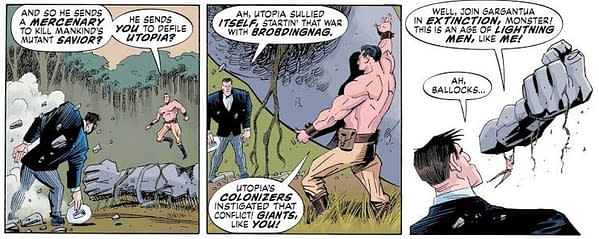

The story came to mind as it was referenced in The League Of Extraordinary Gentlemen: Tempest Book Two, with Utopia going to war with Brobdingnag, the land of giants from Jonathan Swift's Gulliver's Travels, another work of geographic satire from two hundred years later, published in 1726.

A book in which Gulliver ends up finding his wife repulsive, after spending time with the Houyhnhnms, and seeing her –and the rest of humanity–as a primitive and disgusting Yahoos.

Utopia was the first of many books that satirised current human relationships by portraying them differently in a 'utopia'–or dystopia. Famously, early-twentieth-century books, We by Yevgeny Zamyatin, 1984 by George Orwell, and Brave New World by Aldous Huxley were upending sexual relationships, satirizing, and parodying societal expectations and attitudes in very different ways, but also saw the control of sexuality by the state as an effective means of controlling the population in all manner of ways, more than just numbers.

In We, sex is regulated for genetic reasons and state permission must be sought for any relationships, applying for sex visits. The state spies on those deemed undesirable to reproduce and everyone lives, quite literally, in glass houses.

In 1984, sex for pleasure is banned, allowed annually for procreation, as private loyalties compete with loyalty to the state. Celibacy is seen as an ideal, marriages are intended to be unsatisfying and sex vilified, as their scientists are working towards moving to completely artificial procreation, and eliminating the very existence of the orgasm. The young are encouraged to join the Junior Anti-Sex League to back this policy up.

Brave New World went the opposite way, telling us that "everyone belongs to everyone else" with humanity stripped into different castes of genetically predisposed people, born through artificial means. There are no family relationships, humanity is sterilized and what would be called 'free love' is the norm, but portrayed as empty and hypocritical.

Sexuality would become a focal point for many utopian and dystopian worlds. Homosexuality and bisexuality was more common in such fiction, or at least more commonly addressed, including the creation of a number of same-gender societies (both male and female) such as in John Wyndham's Consider Her Ways, Joanna Russ's The Female Man, or genderfluid as in Ursula K. Le Guin's The Left Hand Of Darkness. This was given increased importance in post-nuclear apocalyptic worlds, especially alongside the realisation that radioactive fallout might sterilise many, and other solutions to preserve humanity might need to be found, but also used to comment on the way current society views procreation and sexuality–which also saw a number of women authors dominate that exploration of the genre.

Where Late the Sweet Birds Sang by Kate Wilhelm gave a world where cloning was a necessity, but the resultant fertile clones reject sexual procreation in favour of further cloning, skewing society dramatically and psychologically. The Gate to Women's Country by Sheri S. Tepper sees a future fascist matriarchy controlling sexuality, and removing homosexuality through genetic and hormonal interference, and sterilizing those it deems unworthy, genetically. Margaret Atwood's The Handmaid's Tale has fertile women imprisoned as rape slaves in infertile households. Future Home of the Living God by Louise Erdrich sees pregnant women held in detention centers, and fertile women conscripted to carry embryos. Jennie Melamed's Gather the Daughters created a society where fathers are expected to rape their prepubescent daughters rather than have sex with adult women as a population control measure.

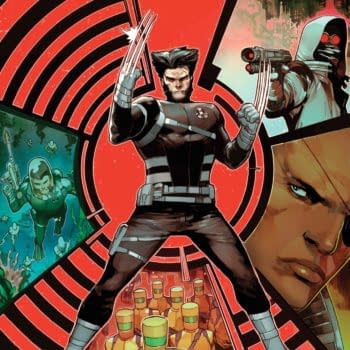

There's a lot of stuff that goes down. And now it appears that Marvel's upcoming Age Of X-Men is about to tread into such territory.

As Bleeding Cool reported yesterday, in the new reality created in a series of mutant books running for six months and starting at the end of this month, humanity is at peace with mutantity. It seems a perfect world, but it is one of restriction. All humans now develop mutant powers when reaching puberty, and all birth now takes place in artificial 'hatcheries', while romantic relationships are forbidden, and mind-wiped out of existence when they occur. Such relationships, seem to include both Nightcrawler and Meggan, and Jean Grey and Bishop–and an unspecified pregnancy is seen as the ultimate rebellion.

Amongst all this, Apocalypse has become the voice of the rebellion–and that voice is one advocating free love (or indeed any love). Apocalypse, rather than the world-conquering ancient mutant in X-Men of old, looks like he will be, basically, a hippy.

Oh, Brave New World, that has such mutants in it? How many allusions to utopias and dystopias past will it contain? What are your favourite takes on the subject?