Posted in: Comics, Vintage Paper | Tagged: Boston Post, H G Wells, war of the worlds

THE ISSUE: Fighters from Mars Attack

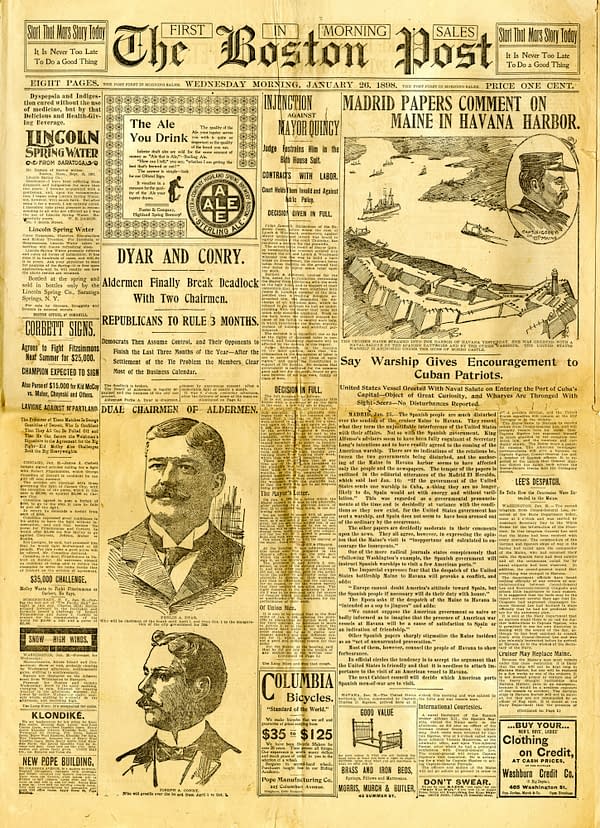

When riots broke out in Havana, Cuba in 1898, the American battleship U.S.S. Maine was ordered to Havana to help stabilize the situation. Cuba had become the focal point for escalating tensions between Spain and the United States. The Maine arrived in Havana Harbor on January 25, 1898. Several newspapers, lead by William Randolph Hearst's New York Journal gained infamy for "Yellow Journalism" during this period. In 1897 Hearst himself reportedly told illustrator correspondent Frederic Remington — who had reported that all was quiet in Havana at that moment — "You furnish the pictures, and I'll furnish the war." On February 15, 1898, the Maine was destroyed by a mysterious explosion, touching off the final spark that made war with Spain a certainty. But just as the Maine was arriving in Havana Harbor in this heated run-up to war with Spain, this issue of the Boston Post from January 26, 1898, had concerned itself with both the arrival of the Maine in Havana Harbor, and also with… Fighters from Mars.

The Issue is a regular column about vintage comics and other vintage periodicals from throughout world history. The idea behind The Issue is simple: for each post, I'll choose something from my collection and talk about what's going on in it, and discuss the publishers and creators behind it. And essentially, I'm just going to end up stepping through comics history one issue at a time. There is only one rule in The Issue: No recent stuff. Everything will be from before 1940, and most of it will be from before 1920.

This installment is a little something that combines comics, dime novels, and history. I've had this paper in my "waiting to research and process" stack for a couple of years. The implications of that front-page headline are obvious: "Madrid Papers Comment on Maine in Havana Harbor. Say Warship Gives Encouragement to Cuban Patriots." But when I pulled this paper out again recently, I took a closer look at the blurb above the masthead: "Start That Mars Story Today. It is Never too Late to do a Good Thing."

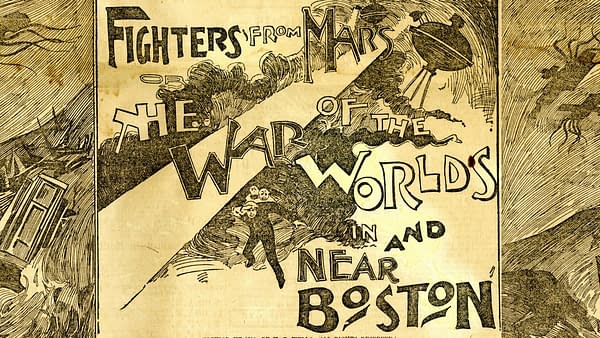

I stared at that for a good while… "start that Mars story?" Am I supposed to be writing a story about Mars? Was there some news about Mars in 1898 that was vitally important to read? Are they telling me to get my ass to Mars…? Opening the paper, the answer is obvious:

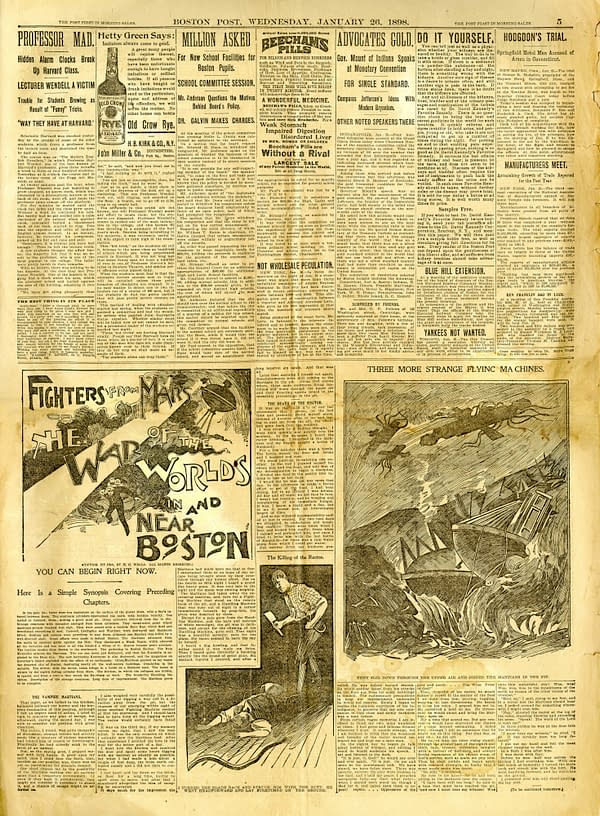

Fighters from Mars: The War of the Worlds in and Near Boston

What is Fighters from Mars? Some sources say that this story is considered unauthorized, but a closer look reveals something far more fascinating. Following up the serialized release of War of the Worlds in Cosmopolitan in the US, altered and localized versions of the story appeared in both the New York Journal and the Boston Post. The Post version is the most heavily altered.

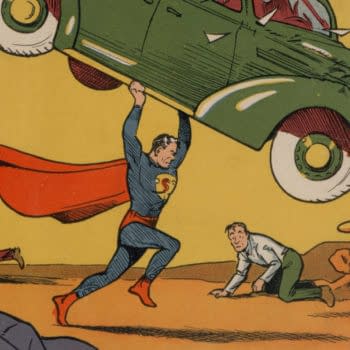

This is pretty clearly an example of fiction used as propaganda. Even one of the illustrations shown here indicates that the Martians are attacking ships at sea. In the text of this installment of the serialization, the story names two real American battleships — the USS Kearsarge and the USS Katahdin — as having been destroyed by the Martians in Boston Harbor. A foreign enemy attacking American ships. And on the front page, the USS Maine has just arrived in Havana Harbor.

While most recent scholarship on this matter is content to believe that the edits to War of the Worlds were unauthorized, I'm skeptical of that. Let's look at what Wells actually did say about the matter, in the March 12, 1898 edition of The Critic:

THE EDITORS OF THE CRITIC:— I have received a rather startling cutting from the Boston Post through the Authors' Clipping Bureau. The cutting is dated Dec. 27, the accompanying invoice is dated Dec. 31, the Boston postmark is Jan. 7, and it has reached me here today. From it I learn that my story "The War of the Worlds" "as applied to New England, showing how the strange voyagers from Mars visited Boston and vicinity," is now appearing in the Post. This adaptation is a serious infringement of my copyright and has been made altogether without my participation or consent. I feel bound to protest in the most emphatic way against this manipulation of my work in order to fit it to the requirements of the local geography.

Yet it is possible that this affair is not so much downright wickedness m a terrible mistake. The story originally appeared simultaneously in the American Cosmopolitan and the British Pearson's Magazine. Mr. Dewey of the New York Journal called upon me in November last and arranged for its serial republication in the evening edition of that paper. In our agreement (of which I have his signed memorandum) it was stipulated that the publication should be with the consent of the American publishers and that no alterations in the text of the story should be made without my consent. On Dec. 26 I received a cablegram from the Boston Post making an offer for the serial reproduction of "The War of the Worlds" "as New York Journal." To this I cabled "Agreed." And now I find too late that my story has been flaunted before the cultivated public of Boston, disguised and disarrayed beyond my imagining. What has been done to it? I fail to see how a rag of conviction can remain in it after this outrage. I do not know what an Englishman may do in such a matter. At any rate I beg you will give me the opportunity of disavowing any share in this novel development of the local color business.

H. G. Wells.

HEATHERLEA, WORCESTER PARK,

Surrey, England, 21 Jan. 1898.

It would appear from the text of the letter that Wells had no objection to the "localized" version that appeared in The New York Journal — the William Randolph Hearst paper that was leading the charge towards war with Spain with full force. So it's not the localization itself that Wells is seemingly objecting to, but perhaps the extent or specific content of some of the Boston Post changes. But had he actually seen the Boston Post version? There's an eyebrow-raising anomaly here because the Boston Post version of the story started 11 days after Wells' claimed clipping service date of December 27. Wells himself notes that the Boston Post only contacted him to inquire about publication rights on the day prior, December 26. Given the time it takes mail to travel from the US to the UK even today, plus the time it would have taken the clipping service to gather, process, and send out the material, it's fair to wonder how — or even if — Wells had actually seen the published Boston Post version of this story on January 21.

Yellow Fiction

Wells's career is laden with work used as propaganda. For example, he was one of the British authors used by Britain's War Propaganda Bureau headed by Sir Gilbert Parker during World War I. It was Parker's job to direct rather extensive propaganda efforts to encourage America's entry into World War I. And as stated in The Great War of Words: British, American and Canadian Propaganda and Fiction, 1914-1933:

As time wore on, writers and public alike knew the war would not soon end, and some of the most eager propagandists began to reflect more deeply. Among them was H.G. Wells, who had spent the early months of the war turning out article after article, mostly of a propagandistic nature.

This was certainly not the last time that War of the Worlds was used as propaganda during the run-up to war. The now-legendary 1938 radio drama version of War of the Worlds by Orson Welles and his British producer John Houseman deserves vastly more scrutiny in this context than it has received. Houseman and Welles had previously met at the Federal Theater Project, a federally-funded project that dissolved in controversy over the political nature of its content. The pair then launched Mercury Theater and Mercury Theater on the Air, where they made headlines the month before airing their version of War of the Worlds with their anti-fascist take on Julius Caeser. After he helped Welles bring America the infamously realistic fictional news of War of the Worlds, John Houseman would go on to bring the world real news of the real World War as the director of Voice of America.

Yellow Journalism is sometimes the very least of such matters to be considered in the context of wartime media throughout history, and we'll be returning to this subject again in The Issue.