Posted in: Comics, Vintage Paper | Tagged: the issue, wonder woman

THE ISSUE: Scientific American and the Hunt for the Invisible Plane

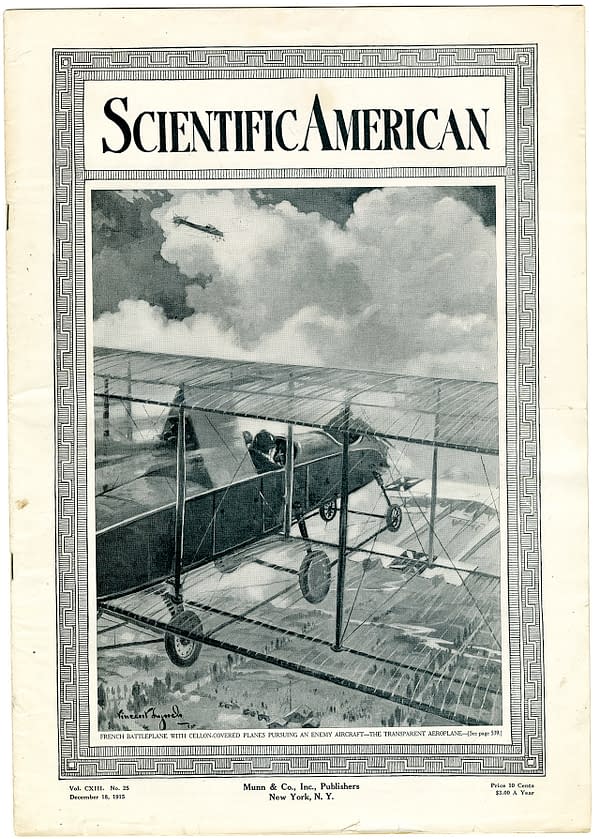

The November 18, 1915 issue of Scientific American and its cover feature about an elusive French invisible plane.

A post from earlier this year about Marvel/Timely's USA Comics #3 eventually led me to the November 18, 1915 issue of Scientific American and its cover feature about an elusive French transparent plane. This feature seems to be the root inspiration for much discussion about the possibilities for "invisible planes" during WWII when it was rediscovered by the media in 1941, likely even helping to inspire Wonder Woman's invisible plane in Sensation Comics #1. The Issue is a column about vintage comics and other vintage periodicals from throughout world history. The idea behind The Issue is simple: for each post, I'll choose something from my collection and talk about what's going on in it, and discuss the publishers and creators behind it. And essentially, I'm just going to end up stepping through illustrated periodical history one issue at a time. There is only one rule in The Issue: No recent stuff. Everything will be from before 1940, and most of it will be from before 1920.

As was noted in the previous post, the featured story of USA Comics #3 centers around a top-secret scientific process that can make planes invisible. That issue hit the newsstands around November 24, 1941, which happens to be about two weeks after Wonder Woman's invisible plane debuted in Sensation Comics #1. That's the kind of coincidence that likely means something during wartime, as comics are full of reflections of war era superweapons from the news of the period. Sometimes such news was propaganda, sometimes not. Newspapers were full of talk about both German and American super-soldiers before Captain America Comics #1 hit the newsstands. The dreaded German V-1 flying bomb influenced several comic book robot planes. Most obviously, the atomic bomb had a dramatic and immediate influence on the course of comic book history.

The Early Days of Stealth Airplanes

Of course, the interest in stealth technology for airplanes is almost as old as airplane flight itself. In one of the earliest widely-read public mentions of invisible plane technology, it was reported in American newspapers in January 1913 that the United States Signal Corps had discovered "invisible" material that was "liquid and is molded into shape, but it is said to be lighter and stronger than canvas and to be adaptable to any description of frame" for use in developing planes that would be practically invisible from 500 feet away for use by the War Department. Despite the mention of a forthcoming public unveiling of this technology, it seems to have never been brought up again. As described, it sounds like an injection molding technique perhaps using a transparent cellulose-based material.

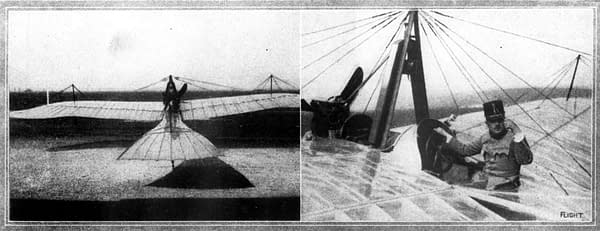

But the next year, UK aviation industry magazine Flight published some rather fascinating photos along with an accounting of work done on invisible planes in 1912-1913 using the material Emaillite, a cellulose-based material developed in France by the firm Ludoc, Heitz & Co. in 1912. Soon licensed for manufacture in several other countries, Emaillite was primarily used as a varnish of sorts to treat airplane wing fabrics to make them stronger and more wind and water-resistant, but could also be used to form transparent sheets in combination with other materials. In 1912, a pilot identified as Lieutenant Nitnner flew an Etrich Taube monoplane with wing and body framework covering largely composed of transparent Emaillite near the city of Winer Neustadt in Austria. This invisible plane was the concept of Captain Petrocz von Petroczy, the former commander of the Austrian army flying corps. Aviation pioneering brothers Jules Albert & André Moreau showed an Emaillite-based monoplane at the Paris Exhibition in 1913, though it seems to have been intended solely as a ground exhibit to promote Emaillite. The Petroczy/Nitnner effort is generally considered the first working use of stealth airplane technology.

In the summer of 1915, the European and American press widely noted the efforts of Anton Knubel of Germany, who was said to have developed and successfully flown an invisible plane that used a material called Cellon in experiments beginning in Summer 1913. Somewhat like Emaillite, Cellon was a clear cellulose-based material, but unlike Emaillite which had to be used in combination with other materials to make sheets suitable for airplane wings, Cellon seemed to have been more rigid in sheet or pane form. As the British licensor of Cellon widely advertised in aviation journals as early as 1912, the material was commonly used for airplane windows in this era and used to treat wing fabrics to make them stronger and more wind and waterproof. Cellon had been patented in 1909 by chemist Arthur Eichengrün in Germany, who is best known as the co-inventor of aspirin while working at F. Bayer & Co in 1897. Eichengrün licensed the manufacture of Cellon to other companies and started his own factory, the Cellon-Werke, as well.

Indeed, despite reports that Knubel was the inventor of the transparent material that made his airplanes invisible, it appears he got his Cellon from munitions manufacturer Rheinisch-Westfälische Sprengstoff, which was licensed by Eichengrün to produce the material. Knubel, reportedly a participant in the first modern Olympic Games in 1896, was a bicycling enthusiast. A longtime bicycle manufacturer, Knubel teamed with aviation designer Karl Rösner in 1910 to build airplanes. Knubel died test-flying one of his invisible airplanes on September 8, 1915.

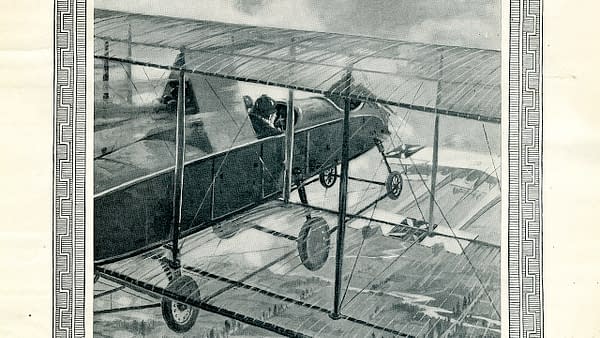

But the concept of invisible planes would have its biggest public moment during this era just weeks later, and in a way that would inform the public's perception of stealth technology for decades. The cover feature of the November 18, 1915 issue of Scientific American asserted that the French military had developed a working invisible airplane that used Cellon stretched over parts of the wing and body framework to make much of the airplane transparent. The article further claims that it was rumored that such a French invisible plane had been put into practice and destroyed a German Aviatik biplane in combat.

The actual existence of this French invisible plane would be the subject of some debate over subsequent decades. Some of the confusion on the matter centered around whether the French could or would have used Cellon, but the material was indeed broadly known and used in aviation at the time and licensed for manufacture in multiple countries. It would further appear that usage of French-developed Emaillite material may have been on the decline by this time because of medical reports of poisoning and even death due to handling Emaillite. We also know that Cellon was used for a small section of the upper biplane wing directly above the cockpit in the French Nieuport 17, to provide the pilot a better upward view around this time.

Neal A. Truslow's Invisible Plane Report

Despite this wide usage of Cellon within the aviation industry, there appears to be scant evidence of the existence of the French invisible plane beyond the original Scientific American feature. The author of the piece, Neal A. Truslow, was a prolific and well-regarded magazine illustrator of his day, who had volunteered with the American Red Cross in France well in advance of the United States' involvement in WWI, and served as a war correspondent for Scientific American in 1915-1916. While there, Truslow submitted a variety of reports on subjects such as German use of machine guns and the effectiveness of French observation balloons.

Truslow also created some covers for his features in Scientific American during his time in France, though somewhat curiously the invisible plane cover is not by him (I haven't been able to identify the artist's signature on this cover at this time). This might suggest he was reporting on an airplane he had not seen or been given a good description of. That said, Truslow's text describes the invisible plane as "similar to the Voisin", and the cover artist depicted a plane that has general similarities to a then-recently-developed Voisin IV firing on a German plane that doesn't seem to resemble an Aviatik or any other known German plane of the period.

It's possible that Truslow's piece was a bit of propaganda in reaction to Knubel's widely-publicized transparent plane efforts on this front from earlier that year. The Scientific American cover and story were recycled by the influential London Illustrated News about two months later and used as the basis for newspaper blurbs worldwide. The United States Naval Institute Proceedings repeated Truslow's report alongside other global military developments around the world that Feburary. The French invisible plane was even used in a 1916 installment of the fictional aviation adventure book series for young readers Our Young Aeroplane Scouts which has the boy heroes of the tale encountering the French invisible plane as described by Scientific American.

While this French invisible plane remains historically elusive, subsequent German efforts to develop a Cellon-based aircraft at this time are better documented, if flawed. German firms including Linke-Hofmann, Fokker, Aviatik, and Albatros Flugzeugwerke all experimented with invisible planes using Cellon beginning in 1916. It appears that at least one Fokker EIII transparent fighter was actually used in combat. According to the book Dark Eagles: A History of Top Secret U.S. Aircraft Programs, on June 9, 1916, the British Royal Flying Corps reported "a transparent German aeroplane marked with red crosses was pursued by French machines in the Somme area". However, these German efforts apparently proved the drawbacks of the concept, as in practice the Cellon material was highly reflective in sunlight, which could not only make it highly visible but also blind the invisible plane's own pilot. The material was also subject to loosening in damp weather.

After WWI, the notion of practical invisible planes began to shift towards methods of camouflage via paints and other means, but the notion of planes composed of transparent material didn't fade away completely. In 1921, an inventor named Ernest Welsh claimed to have made "a metal with the transparent properties of glass" for use on airplanes, and as late as 1939, inventor Morris E. Heisner claimed to be developing a transparent plastic airplane called "The Heicolode". Neither of these purported developments seems to have gone anywhere. But in the mid-1930s, Sergei Grigorevich Kozlov, of the Soviet Union's Nikolai Zhukovsky Air Force Engineering Academy, experimented with using Cellon on a Yakovlev AIR-4, developing an airplane designated the Kozlov PS (PS for Prozrachnyy Samolyot, meaning transparent aircraft). Likely the most notable post-WWI attempt at a workable transparent airplane, the Kozlov PS reportedly had similar drawbacks to the previous Cellon airplane experiments, and ultimately was not pursued past the experimental stage.

In the WWII era, the saga of the invisible planes starts in earnest in the Fall of 1940, with rumors of the development by the British of light-absorbing paint or varnish that could render planes invisible even from a distance of six feet. The claim as written here is a bit of obvious propaganda, but seems to have led to a tidbit in the December, 1940 issue of the industry trade journal Plastics reviving the possibilities of invisible planes via the use of transparent plastic polymers. This in turn appears to have given rise to rumors that the Nazis were doing exactly that, sparked by a piece in a January 1941 issue of the British journal The Aeroplane which was widely repeated by newswires. Plastics magazine brought the story back into newspaper headlines again in June 1941 by reminding readers that not only was an invisible plane using transparent materials possible but it had actually been done already in World War I. The Plastics piece focused on the concepts as discussed in the Scientific American cover feature, while admitting that this technology likely had little application with the aerospace state of the art of the 1940s.

Nevertheless, media reports of these ideas in mid-1941 likely helped inspire the invisible plane concept in comics like Wonder Woman's Sensation Comics #1 later that year, just as happened with so many other wartime developments during the period, and it was largely prompted in the media by the revival of this 1915 Scientific American story. While there were still advanced efforts at optical stealth during WWII such as Project Yehudi, the advent of the practical use of radar and other factors changed the game for the requirements of the notion of stealth technology during that war and beyond.