Posted in: Comics, Vintage Paper | Tagged: pulps, spicy history stories

Blind Item: The Strange Pulp Legacy of William d'Alton Mann

Spicy History #1: William d'Alton Mann is credited by many with the creation of the blind item and blackmailed America's elite, but also left his son with a pulp publishing legacy.

Unsurprisingly, periodical publishers of the late 19th and early 20th century were often people with appetites for risk and adventure in equal measure. The legendary Hugo Gernsback is a good example from this history, and his early efforts in electrical engineering, manufacturing and radio seemed to lead naturally to his publishing endeavors. For other magazine industry innovators, the path to publishing was much less straightforward. For example, Fiction House founder John W. Glenister had careers as a professional swimmer and vaudeville performer before practically stumbling into the publishing business. Glenister, whose claim to fame was that he was the only man to ever swim the whirlpool rapids below Niagara Falls, certainly had an appetite for risk and adventure, but he seems to have wandered into magazine publishing via sports writing and found he had a knack for the business end.

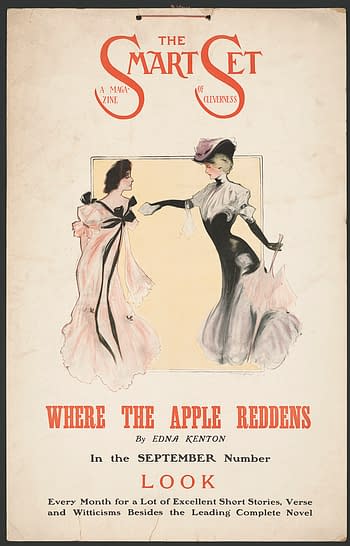

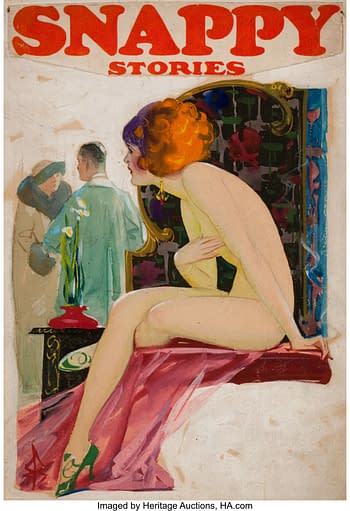

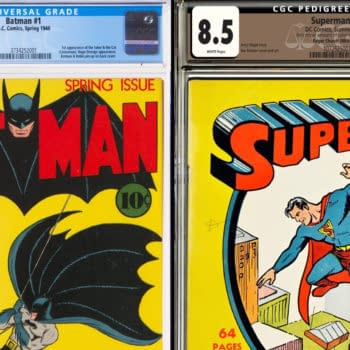

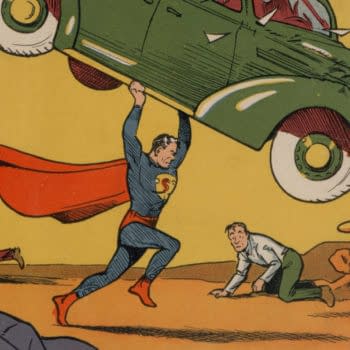

We can add William d'Alton Mann to the list of publishers of that era from the Glenister end of the spectrum of people whose path into pulp publishing seemed almost accidental. Under the later guidance of his son William Mann Clayton, the publishing empire that William d'Alton Mann began would eventually include legendary pulp titles like Strange Tales and Astounding Stories. The elder Mann himself had previously launched Smart Set and Snappy Stories (the latter along with his son). But before that, William d'Alton Mann's life and career would see him serve as a Union colonel in the Civil War, lead him to found a railroad car company that would go on to launch the Orient Express, and become a figure that the most powerful men in America feared.

Welcome to Spicy History Stories #1, the first installment of a weekly column about pulp magazine history that we're launching to coincide with the debut of Heritage Auction's weekly pulp magazine auctions. Unlike other auction-centric posts we've done here, this column is not necessarily designed to be closely tied to any particular items up for auction. Mostly, it's this: if you enjoy the nerdy details of comic book history, you're going to love the astounding (and yes, sometimes weird) history of the people and companies that made the pulps.

Civil War, Oil, and Accouterments

William d'Alton Mann was born in Sandusky, Ohio in 1839. Mann received an education in civil engineering, married in 1855, and was living in Michigan with several family members by 1860. After the outbreak of the Civil War, Mann entered the army in the 1st Michigan Cavalry as a captain. He became a colonel of the 7th Michigan Cavalry in late 1862. Brigadier General George Armstrong Custer was given the command of the Michigan Cavalry Brigade the next June. About Mann's performance during the Battle of Gettysburg that July, Custer would say "Colonel Mann is entitled to much credit" in his official report.

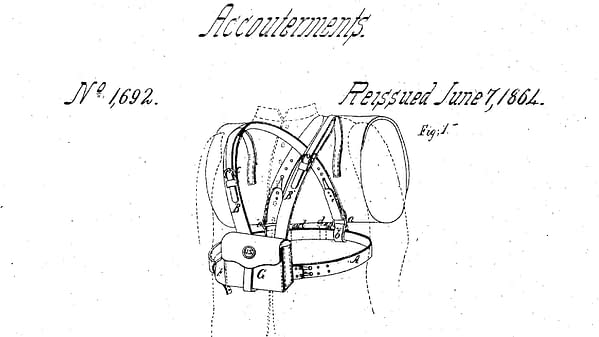

Drawing on his engineering background, Mann would make his first foray as an entrepreneur before the end of the war. According to documentation, Mann would develop and patent infantry accouterments for carrying ammunition and other supplies, which according to some sources, were manufactured and used before the end of the war. Examples of Mann's accouterments are of interest to collectors and historians to this day. An 1864 letter from General Ulysses S. Grant stated, "An examination of the cavalry and infantry accouterments exhibited by you satisfies me that the change from the old style is such as to warrant their adaption throughout the army as fast as the new accouterments have to be supplied."

As it would later emerge in court, Mann had solicited the assistance of a number of Union Army officers, including General Joseph Hooker, in exchange for a share of the accouterments company and its profits. With an oil boom underway during the war era, Mann would amplify this strategy for his next business venture. Enlisting the investment of even more Union Army officers in 1865, Mann formed The United Service Petroleum and Mining Company, enticing Major-General Winfield Scott Hancock to invest and serve as president of the firm. Long and complicated story short, this oil speculation scheme ended when some of the participants submitted a criminal complaint of fraud against Mann in New York City. He was ultimately acquitted, with the judge citing a lack of jurisdiction and noting that the complainants would be better served to pursue the matter in civil court. None of them did, but Hancock's role in this headline-making incident was revived and rehashed in 1880 after he received the Democratic Party nomination to run for President of the United States.

The Alabama Publisher and Tax Man

After that rather public setback, Mann's life took another odd twist when in 1866 President Andrew Johnson appointed him as the Federal Assessor of Internal Revenue for the first district of Alabama. The fact that Mann got an Internal Revenue job that required nomination by the President and confirmation by the Senate, for a role giving him significant power over the financial fate of others just a year after creating national headlines over his own financial scandal, is perhaps a testament to his growing network of powerful acquaintances and his ability to leverage it.

It was at this point that Mann made his first entry into publishing. Events on the ground after Mann moved to Mobile, Alabama lack some historical clarity, but by his own account, he loaned money to the operators of three of the city's four newspapers, until he had effective control over the Evening News, the Register and Advertiser, and the Times. He then rolled these businesses into one paper called the Mobile Register. There is some debate over Mann's political stances with the newspaper, but in 1868, the former Governor of Alabama Lewis E. Parsons wrote to President Johnson to support Mann's elevation to Supervisor of Internal Revenue for the districts of Alabama, Georgia, and Florida. In the letter, Parsons said, "He is a Union Man. He and his paper will stand by you with your friends in the present and future. In helping him to this office Mr. President you are aiding the cause for which you have struggled so long and with such unparalleled devotion."

Mann was denied that promotion, and ran for Congress in 1869 as Alabama formally reentered the Union. It has become a part of Mann's biographical lore that he won the election in a landslide but was "counted out by the carpet-bag managers of the Reconstruction State Government" who blocked the victory, but as pointed out in the Mann biography The Man Who Robbed the Robber Barons, this is unlikely. It appears that Mann had won Mobile County with 60% of the vote and lost the rest of the district. Incoming President Ulysses S. Grant also nominated another man to take his place as Assessor of Internal Revenue for the district that year.

The Path to the Orient Express

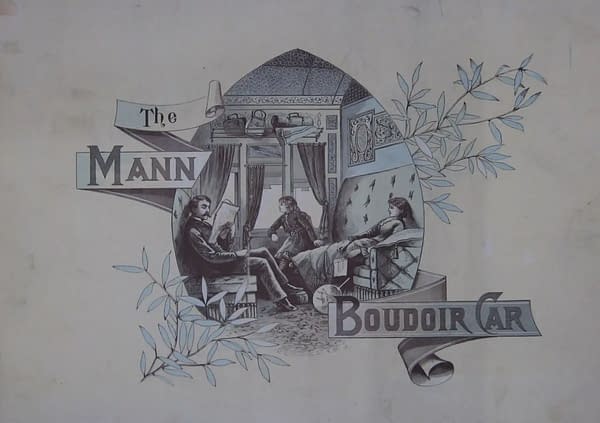

But with these setbacks, Mann turned to new opportunities. Leaning back into his entrepreneurial roots, Mann invested in a cottonseed oil refinery in Mobile and a railroad line called the New Orleans, Mobile, and Texas. The railroad business would prove to be the beginning of another major career axis of Mann's life. Apparently struck by the rapid financial success of George Pullman's sleeping car concept for trains, Mann designed and patented his own sleeper car concept in 1872. Mann then went to Europe, where Pullman had not yet established his sleeping cars, in an effort to promote what he called the Mann Boudoir Car.

By the account of railroad historians, Mann established the first sleeping car in Great Britain, and made inroads in Germany, France, Belgium and the Habsburg Empire. He joined forces with Georges Nagelmackers in 1874, and Nagelmackers assumed control of the company from Mann in 1876, renaming it The Compagnie Internationale des Wagons-Lits. Nagelmackers and his backers reportedly completed the buyout in 1882, and continuing to use Mann's patented designs, in 1883 launched the Orient Express — a name that became synonymous with luxury train travel. Mann returned to New York City that year and attempted to go up against Pullman in the U.S. with little success. The Union Palace Car Company bought the Mann Boudoir Car Company in 1889, and was in turn acquired by Pullman.

The Saunterings of Town Topics

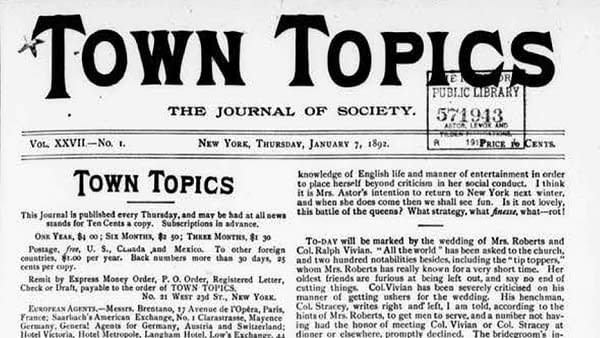

In 1885, William d'Alton Mann embarked on the most notorious stage of his career by making his mark on the American publishing field in a significant way. He backed his brother Eugene Mann in purchasing the weekly magazine American Queen, renaming it Town Topics. The new weekly became a legend that endures to the present day. As the Columbia Journalism Review put it in 2006, "Mann took over this moribund weekly and, with the instincts Gilded Age Tina (or Graydon), turned into reliable font gossip about the antics the super-rich. Mann's business plan worked like charm. Town Topics became a must read, not only for the wealthy who were politely skewered in its pages, but for the hoi polloi, who considered Vanderbilts, Astors, Harrimans, and Whitneys not just Great American Families, but a fine source of entertainment well. Mann has been justly praised as the godfather of modern gossip. He is also credited with the invention of the "blind item," whereby the salacious details of an embarrassing event are printed, but the identity of the subject only hint-at. ("What playboy was seen, at 3 a.m. stealing out the Newport cottage of which prominent social leader, while her husband was New York?") Clever enough by far, but Mann took it a step further. In a nearby paragraph the real name of the erstwhile subject was inserted into an innocent-sounding passage about, say, the recent fete given by Mrs. John Jacob Astor."

Mann acquired his gossip from "a roster of spies to rival that of the National Enquirer in its heyday: maids, butlers, telegraph operators, deliverymen, and down-and-outers who

then paid reporters" to deliver this dirt in a section of Town Topics called Saunterings. As would later be revealed in court, Mann also used his information for blackmail, by asking prominent subjects of gossip for money if they wished to keep their names out of Town Topics. It came to light that the likes of J.P. Morgan and William K. Vanderbilt had given him $200,000, for example.

This scheme began to unravel when Town Topics attacked Theodore Roosevelt's 20-year-old daughter Alice in 1904: "From wearing costly lingerie to indulging in fancy dances for the edification of men was only a step. And then came—second step—indulging freely in stimulants. Flying all around Newport without a chaperone was another thing that greatly concerned Mother Grundy. There may have been no reason for the old lady making such a fuss about it, but if the young woman knew some of the tales that are told at the clubs at Newport she would be more careful in the future about what she does and how she does it."

This resulted in a public outrage, which included an attack on Mann in Collier's magazine, over which Mann sued Collier for libel. The resulting court testimony was damaging to Mann and Town Topics, they lost the case, and Mann was indicted for committing perjury on the stand. Town Topics continued on with a bit less bite than before.

Meanwhile, Mann had launched the now-legendary fiction magazine Smart Set in 1900. The original idea of Smart Set was to be a sort of fictional companion to Town Topics. If gossip about New York City's rich and famous was successful, perhaps the fictional exploits of the Park Avenue crowd would be as well.

Mann was forced to sell the Smart Set to John Adams Thayer in 1911, but Mann's son William M. Clayton had begun to learn the magazine publishing business on the staff there. Clayton would launch Snappy Stories in 1912, using the corporate shell New Fiction Publishing Company that by most accounts his father had established, perhaps to help launch his son on his own career. William d'Alton Mann died at the age of 80 in 1920. Snappy Stories would inspire a number of later imitators of the Saucy, Breezy, and Spicy variety. William M. Clayton would go on to publish a number of memorable magazines and pulps, including Strange Tales and most memorably, Astounding Stories. We'll get into Clayton's career next time.

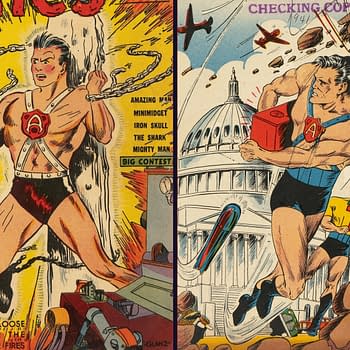

- Smart Set promotional poster, 1906.

- Snappy Stories cover prelim, Enoch Bolles.