Posted in: Movies, Recent Updates | Tagged: soldier, spy, tailor, tinker

Look! It Moves! #136 by Adi Tantimedh: Smiley, Then and Now

Finally saw the Nu52 reboot of TINKER, TAILOR, SOLDIER, SPY this weekend. It's a fascinating exercise in adaptation and period reconstruction.

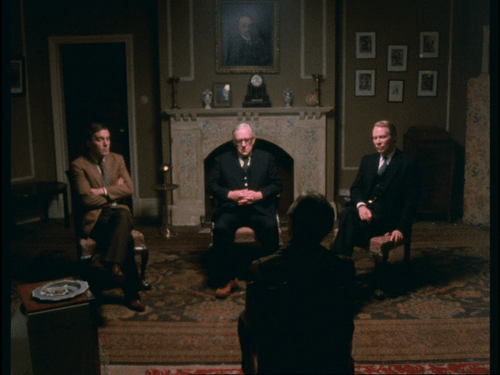

I read the book when I was a teenager and again in college, and watched the 70s BBC miniseries on DVD in the 90s. Considering the BBC series was made in the time in which it was the book was set, and in keeping with the slower pace of BBC drama of the time, it practically felt like documentary. The BBC's brief is often to faithfully adapt a book, including translating the dialogue verbatim, which is a blessing considering le Carré's gift for dry wit and Oxbridge bitchness.

Tomas Alfredson's new movie had the daunting task of translating a dense, thick novel that needed over five hours of TV to explain everything into a two-hour feature, and there was always a danger of losing too much from the book to do the story justice. Since I already knew the whole plot and whodunit, it was more interesting to me to see how the pieces were reconfigured and put back together to form a coherent movie. Alfredson has pulled it off, though the movie is a different animal from the book and the TV version. The movie is tailored, as it were, to be a cinematic with a capital C. It uses sound and editing, wide shots and close-ups to scream 'MOVIE'. It makes the bold choice of cutting out nearly three-quarters of le Carré's dialogue to tell the story through visuals and elliptical sound cues as much as possible recreating the oblique quality of the novel in a new way.

Alfredson's movie is all silences and glances, unmade gestures and unsaid words. Where the BBC show was all naturalism, the movie is hyperrealism, the 1970s as a Science Fiction, a cold, forbidding alien planet we should be glad we don't live on. Where the book and the TV version was a series of conversations and dialogues where Smiley and the cast talked their way through to a solution, recalling the past and crucial details through the telling and retelling of stories, the movie is about memories recalled at crucial movements, flashbacks as Proustian moments. The TV version was about the slow murkiness of the maze of spy games while the movie is about reaching through the haze to drag essential images and revelations into the light of a carefully-framed tableau. New scenes are created for the movie that were never in the book, and the presence of Smiley's late boss Control, shadowy presence in the book whose influence was still felt long after his death, is more literal and present in the movie, played by John Hurt and achingly alive, paranoid and right in several flashbacks.

Where the TV version featured grey men in anonymous corridors and offices that were still around when it was shot, the movie creates a lost world, more vivid but no less cold, conspicuous in its intensely gaudy production design as if to it was a 1970s constructed from myth. Yes, both the TV miniseries and movie remind us of how miserable the 1970s were. One of the things that struck me about the movie is how it identifies that decade through horrible wallpaper as background against which the characters have to stand against. And there are a lot of shots of men standing staring off meaningfully into the distance in widescreen. There are probably more shots of the back of Gary Oldman's head here than in his entire career before this.

What's interesting is that the movie has been a critical and commercial hit in the UK and doing quite well in the US. The screening I attended was sold out and not a teenager in sight, seemingly full of adults desperate for a movie that catered to them that wasn't another action movie based on a comic book and CGI'd up the arse. I wonder if the movie also appeals to nostalgia for the Cold War, when having the Soviets as enemies was a miserable but comforting certainty compared to the chaos and confusion of the present. The movie actually depicts, as the novel did, the grey Old Boys' Network of spies as a state of mind and a stagnant existential maze with the Soviet threat almost an abstraction despite the bursts of violence and threats of death. It's the flipside of the glamour of James Bond, a more buttoned-down fantasy that's equally macho in its determined greyness. George Smiley is the nerd as spy hero, a man whose weapon is his brain as he sits piecing puzzles together until he finds the right answer. Fans of spy fiction might wish they could be James Bond but realise deep down how unrealistic that is, but they might achieve becoming George Smiley if they just sat down and thought about things long enough. The appeal is just as strong.

There's a mole in my coffee at lookitmoves@gmail.com

Follow the official LOOK! IT MOVES! twitter feed at http://twitter.com/lookitmoves for thoughts and snark on media and pop culture, stuff for future columns and stuff I may never spend a whole column writing about.

Look! It Moves! © Adisakdi Tantimedh