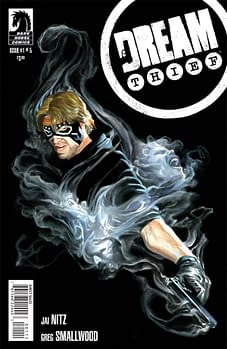

Posted in: Comics | Tagged: dark horse, dream thief, greg smallwood, jai nitz, reviews

The Crazy Amorality Of Dream Thief

The promo from Dark Horse for Dream Thief #1 warn you that "spirits of the vengeful dead" are going to "possess" John Lincoln and turn his life into a nightmare, so there's plenty of mental preparation provided for the darker side of this new series written by Jai Nitz (Heaven's Devils, Green Hornet) and drawn by impressive semi-newbie Greg Smallwood. They really pack the storytelling into this origin issue, but what you find out about Lincoln is both off-beat and surprising, and Smallwood's artwork has a subtle way of getting under your skin enough to suspect that things are about to become quite a nightmare for John Lincoln.

Lincoln's rather a sad bastard, for one thing, struggling from moment to moment to keep his life together, and unlike many sad bastard tales, Nitz and Smallwood really crack down on allowing any sympathy to develop for the character. It's part of the tone of the book to keep you quizzical, and they elevate that to an art, really, by taking you as far as they can into Lincoln's fairly vapid life in extreme detail. The structure of the story is overtly crafted to hint at things to come, from Lincoln's dad's strange letter delivered in parts overlaying early scenes to Lincoln waking up, not sure of where he is for mundane reasons. It's important that the story introduces Lincoln's thoughts early on since they will be the guiding force through the unusual premises of the book later on, too.

From a more successful and attractive best friend to a deeply troubled relationship, Lincoln seems to have all the cards stacked against him, but again, no sympathy because he comes off as rather passive, stumbling through life without really addressing the issues that plague him and retreating into a pot haze to inspire him to lie to his girlfriend to cover up cheating on her and no doubt dull the edge on realizations that he is broke and pretty clueless. These details may suggest that the book is rambling and unappealing, but that's not the case. A strange tension slowly builds up as we follow Lincoln through his life, and part of that is due to the intentionally disorienting page layouts that jump between color schemes and locations to form a collage-like introduction to Lincoln's average lacklustre day. He does the wrong things, he says the wrong things to his sister and traumatized girlfriend, and he sees himself as a man assailed by the difficulties of life.

There's an abruptness to Lincoln suddenly turning up at a museum party with hunky friend Reggie that suggests that Lincoln is well outside of his natural element: he hardly seems like a museum-goer, but that works well because what kind of average museum goer (again in a pot haze) would steal a priceless aboriginal mask. The disaffected kind, the kind who feels that life can't get much worse than it already is. If there's any sympathy for Lincoln in the book, that's where it exists, in the fact that he thinks things can't get worse, but they do get so much worse, really, for a guy who just doesn't want to engage with his problems. He's not a hero or an anti-hero, John Lincoln, and that makes things a little frightening for the reader. He's a mediocre guy who's fairly self-absorbed. What happens when someone like Lincoln gets "possessed" by vengeance? What kind of moral compass is going to guide that train wreck? At 10 pages, all of Lincoln's amoral qualities suddenly become a problem in a big way. They become suddenly significant and alarming because he becomes a kind of psychologically unstable weapon. Reassessing the daily life we've seen from Lincoln, we know he avoids cops, deals with petty criminals, cheats without compunction on his girlfriend and wants her to just "get over" a psychologically scrambling home-invasion she's been dealing with. It's not an inspiring picture. He rationalizes everything he does, so how's he going to rationalize the most extreme behavior that he may suddenly be capable of?

Does that mean he's suddenly an absolutist in terms of personal morality? An eye for an eye is one of the most ancient moral codes in human civilization, but the truth is that Lincoln is now in the grip of many moralities, as many as the variety of tormented souls who may possess him. And they are all convinced that they are right to do what they are doing, killing their killers. Maybe they are, and may they aren't. A reader would be likely to judge this on a case by case basis. Lincoln's girlfriend was a very unpleasantly ambiguous case, and it remains to be seen what could possibly justify the mass killing Lincoln finds himself in the midst of as the first issue ends. But that's the question, and it's a very psychologically engaging way to address readership, to ask them to weigh Lincoln's actions as the Dream Thief, and to decide to what degree he is actually culpable for his actions. One of Smallwood's greatest artistic strengths in this comic is to keep psychological realities hovering on the surface. The reader's role as observer actually becomes a little maddening as we watch Lincoln drift through life and into shocking actions because we want more exposition and explanation, but the artwork is intentionally not yielding that information, building suspense, until important moments when inside-views are offered. When Lincoln recalls the mentality of his first vengeful spirit, Smallwood employs a serpentine, flowing grid of images across a double-page spread to fill you in on what you need to know. And he keeps that information on a need to know basis. Smallwood's depictions of Lincoln actually encourage you to wrestle with your knowledge of the evolving character as much as Nitz's writing does.

Hannah Means-Shannon is a comics journalist and scholar working on books about Alan Moore and Neil Gaiman for Sequart.org and is a contributing editor at TRIP CITY. She is @HannahMenzies on Twitter and @hannahmenziesblog on WordPress.