Posted in: Comics | Tagged: Adam P Knave, D.J. Kirkbride, dark horse comics, Never Ending, Robert Love

Who Wants to Live Forever? Dark Horse's Never Ending Will Make You Think Twice About Being a Good Guy

What is it that really motivates superheroes to do the good things they do? In some cases, we see them driven by revenge and grief, and at those time, we understand their behavior even as we question it. For superheroes who used to be "normal", like Chuck Baxter in Dark Horse's new mini-series this week, Never Ending, his do-gooding is at least partly motivated by the encouragement of his wife who acts as a source of inspiration. That's humanizing, too, as a detail. We can understand the way in which people in our lives can make us feel superhuman and even be the motivation for betterment. But what if, like Chuck, you find as time passes, that you're immortal, and so it's inevitable that your source of inspiration will, too, pass? Would you continue to be a champion for people in need, or even for the government, purely in memory of a loved one?

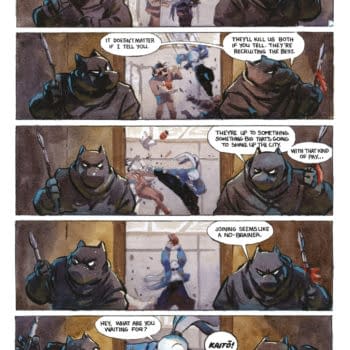

In Chuck's case, he's prepared to admit that he's locked in a legacy of struggle that he feels he helped create and therefore he must continue. Archibald Crane, the scientist originally tasked to study his meteor-bestowed superman-like powers has become his nemesis. Employing science and technology to keep himself going as long as Chuck, the two continue to clash again and again. It's become a decades-long Groundhog Day for Chuck, and he comments, "Nothing ever changes". They are trapped in a loop that provides a fairly telling commentary on the way in which are superheroes are rebooted, resurrected, and essentially rendered endlessly young while they are stripped and overhauled in personal relationships to keep that loop functioning smoothly.

In fact, Chuck's marriage and family, the loss he must face when confronting mortality is exactly what the Big Two grapple with, or avoid entirely in super hero comics. Writers Adam P. Knave and D.J. Kirkbride, and artist Robert Love hit that problem head-on and it's one of many of those niggling problems inherent in the premises of superhero comics that they haul out into the daylight of emotive scrutiny.

Firstly, Chuck Baxter, unlike Superman, his counterpart in powers and in costume color-scheme (though the nifty tunic design and utility belt are more visually interesting than Superman's costume), was once a mortal human and remembers "being powerless". Secondly, he's tied to his 1950's generation by love and devotion to his wife, and will experience the realities of time through her. Thirdly, he's self-aware of the combat loop he's trapped in against his nemesis, a science-based supervillain.

But there's something else that's even less common in superhero comics than these extra layers added to common tropes: he may well be, having assessed his experience and role ad infinitum over the decades, ready to die to free himself from this soul-defeating cycle. All of these things seem to dictate that Chuck must continue in his role as a "good guy" serving his society, even though he realizes it's been "years" since he did anyone "actual good". It's hard to escape the possibility, or even the suggestion, in the comic that being an immortal good guy mighty, in itself, eventually bring you down.

There's one big "if", though that may challenge this assumption. If Chuck didn't continually face the same super-villain in a conflict for which he feels partially responsible, would his good guy lifestyle be any easier? And yet the classic nemesis and the endless combative cycles are entirely typical of Superman and Batman narratives, for instance. They are deeply embedded in the superhero tradition, and they do help popularize certain super-villains who are as classic as the heroes themselves. If Chuck didn't have his super-villain, would he still, essentially, be depressed? He might be able to change, to evolve, to move forward in some ways, but he might also be pulled back into his memories of loss and feel increasingly alienated in a changing world.

In the first case, being a good guy might become rewarding again, and in the second, the burden of continuing to be a good guy would be an increasing burden. Which will it be for Chuck? Something has to give. One thing is certain, it's not an enviable position. The fact that Never Ending manages to establish all this and critique superhero tradition in such a detailed way in a single issue is impressive. That makes the comic a matter of interest for our assessment of the hero tradition, and it may even shed some pretty insightful light on the problems that seem to constantly beset the vitality and structure of mainstream superhero comics.

Hannah Means-Shannon is Senior New York Correspondent at Bleeding Cool, writes and blogs about comics for TRIP CITY and Sequart.org, and is currently working on books about Neil Gaiman and Alan Moore for Sequart. She is @hannahmenzies on Twitter and hannahmenziesblog on WordPress. Find her bio here.