Posted in: Movies, Video Games | Tagged: Alien Isolation, assassin's creed, call of duty, Fallout 3, mass effect, the last of us, video games, violence in gaming

The Meek Shall Inherit The 1UP: Non-Violence In Gaming

By. J. Michael Neal

The recently released Alien: Isolation made headlines when it was announced that the game would give players the option to complete it without killing anyone. This news was upsetting in its newsworthiness – the fact that a game that allows you to not kill things is a refreshing change of pace. Obviously not all games involve killing, there are entire genres devoid of the mechanic, but as I look through my gaming library, as I go down the sales charts, as I browse the upcoming lineups, some sort of violence seems to factor into everything I see. This was an issue I first encountered while introducing an ex-girlfriend to video games.

I have long been a proponent of the unique narrative strengths gaming, and a walking rebuttal to the "games are not art" debate since high school. I can quickly reel off dozens of examples to anyone foolish enough to question the depth and variety of the video game landscape in my presence. Yet, when it came time for me to sit down with someone completely unfamiliar with video games, who had never held a controller before in her life, and introduce her to this game worth playing, and that game worth playing, I found myself repeating the same words over and over. "Attack". "Kill". "Fight". "Shoot". "Destroy". She had no issue with this, but I did.

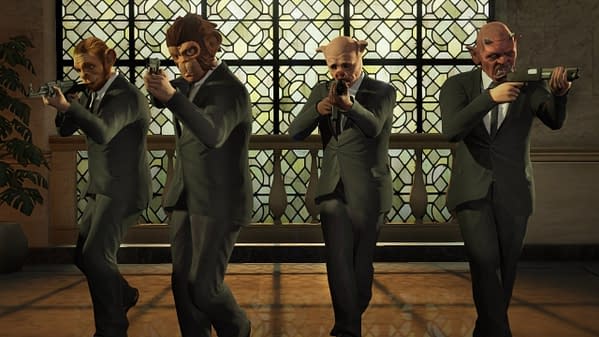

She ate up everything I gave her. Mass Effect. Fallout 3. Assassin's Creed. The Last of Us. But the more games I guided her through, the more I heard myself saying those same words again and again – "press the attack button", "shoot this", "destroy that", "kill him", "you died". Something was wrong here. Every game with an awesome story to tell seemed to tell it down the barrel of a gun, or at the tip of a blade. Can't she just be allowed to absorb Rapture's submerged dystopia and complex philosophical and sociopolitical debate without having to shoot things in the face? Can't she just enjoy Los Santo's rich American satire without murdering half the population of the state of California? I can name a hundred books, movies, and even comics that manage to do so without killing something every 60 seconds, but suddenly my list of games that can seems to be shrinking.

"We are playing AAA titles on the Xbox 360 and PS3", I told myself. "What was I to expect? Maybe if I tried more indie games, or a family friendlier system it would be a different?" But I found that it was almost inescapable. I began to notice the theme running through things I never even noticed before – mascot driven platformers, kart racers, puzzle games. Unless you want to guide a flower petal on the wind, or return home and try to figure out why your entire family left their house, this terminology, this imagery, this play mechanic of killing, death, destruction, and aggressive conflict reappears time and time again.

Again, not all games are violent, and I can give just as many examples as anyone of the ones that aren't, but as you move up the scale from indie titles to the "AAA" games that dominate both sales charts and GOTY lists, they seem to get fewer and farther between. There have been some highly successful, big budget titles that give players non-lethal options, mind you. Hideo Kojima's bluntly political Metal Gear series has always been the most prominent – coating a soft, pacifistic center in a crunchy shooter shell. It's become such a trademark of the series that even the Ninja Gaiden-style hack-and-slashfest Metal Gear Rising: Revengeance had a no kill option.

Perhaps because of the formula Metal Gear Solid created for the genre, stealth-based games are more likely to give players non-lethal options. The problem is, however, games like Thief, Splinter Cell, Deus Ex, and even Metal Gear present non-lethal playthroughs as the "challenge" option. It is more difficult to finish the game by not killing; requires more patients, skill, or timing; usually increases risk to the player or greatly extends play time; and often involves a smaller pool of resources, options, ammunition, or weapons. This not only indirectly discourages non-violent choices, it falsely presents the idea that non-violent conflict resolution is somehow more difficult than violent conflict resolution.

How many of your daily problems do you solve with violence? How many problems in your life period do you, or have you, solved by killing someone? Or a lot of someones? I'm going to guess, for the vast majority of you, the answer is zero. Taxes, debt, unemployment, slow people walking in front of you, the waitress forgetting you asked for dressing on the side instead of on your salad – for any sane person violence isn't an option in any of these scenarios, so we have to find other ways to deal with them, and do so with ease.

Game developers would have you think, however, that every problem has a solution as long as you still have bullets in your clip. The Bruckheimerian realm that games inhabit live on the principle that no dilemma is too big or too small to be solved by a well-timed explosion. Is your girlfriend kidnapped? Were you just abducted by aliens? Is an ancient prophecy about to be fulfilled? Is that door locked? Sounds like someone needs to die! Violence is often the only option (or at least the quickest, easiest, and most efficient one) in far too many games. So was the case when bullets where single pixels blipping across the screen and so is the case now.

This way of thinking has become an indelible part of the community, from the way we approach games as designers to the way we approach them as gamers. I think this is why we see games that dabble in non-violent options but are afraid to commit fully. The excellent Deus Ex: Human Revolution took heat for invalidating the tremendous freedoms given to various stealth and non-violent play styles by throwing in boss battles that required pure run and gun tactics, a problem later corrected in the Director's Cut. There was near universal agreement that the entire shooting mechanic in DICE's amazing Mirror's Edge should have been revamped, but would have probably been better off left on the cutting room floor. And there seemed to be a collective groan when the incredibly promising Watch_Dogs buried the intriguing "you're a super hacker and your smartphone is your weapon" premise inside a lackluster GTA-clone. I think we as players and designers alike have a genuine desire to see an increase in non-violent options in games, but just can't seem to give up our fully-automatic security blankets.

Like Metal Gear, games would rather safely explore the issue of violence from within the context of a violent game. Titles such as Far Cry 3, The Darkness, Spec Ops: The Line, Red Dead Redemption, and Shadow of the Colossus, just to name a few, all take a critical look at violence while still using violence as the primary play mechanic. While there is nothing wrong with that, the fact that close to no one outside the indie market is attempting to handle the subject any other way is disappointing. It's easy to make a Full Metal Jacket or an Apocalypse Now; It's a lot harder to pull off a To Kill A Mockingbird. Probably the most noble attempt to date comes from Mass Effect and its trilogy-spanning narrative that, while again reliant on violent play mechanics, forces players to deal with the consequences of all their actions in some refreshingly soul-crushing ways. No life taken is ever done lightly and none are without repercussion.

One genre that has successfully embraced offense-deprived gameplay is the horror genre, but this too is problematic. Games like Amnesia, Slender, and Fatal Frame use the unarmed antagonist as a means to intensify the action. The inability to attack equals weakness and helplessness, and helplessness is terrifying. Limiting ones ability to defend oneself has been a trope of the survive horror genre since Resident Evil decided to make bullets more precious than gold (although luckily the whole limited save thing has fallen to the wayside) and using it has been shorthand for horror ever since. In fact, the intensity level of a horror game is directly proportional to how much offensive power you are given. There is a gradient scale of terror, with games like the never-out-of-bullets-or-flares Alan Wake at the bottom, games like start out with a peashooter but end up strapped Dead Space near the middle, and the "all you can do is run and poop your pants" Outlast at the very top.

This idea that nonviolence is equated to weakness, and weakness is scary, is most likely traced back to gaming's roots as the pastime for young and adolescent boys. It's an insecurity that has the fingerprints of hegemonic masculinity all over it. Video games, like all escapist entertainment, often function as a form of wish-fulfillment, and the violent outlet is a way to make people feel stronger. Solutions are just a right-trigger pull away because in the real world they aren't that simple. But what if non-violence wasn't a form of weakness in a game? Or was a logical, easier, and more rewarding option than killing? What if action games trusted your brain more than your aim? If violence were taken off the table and replaced with other, more creative, and actually more realistic means of conflict resolution and problem solving it might have lasting positive impacts that went beyond the world of gaming.

I'm not saying a new Call of Duty in which players hug it out and talk through their differences would blaze the charts (or even be remotely enjoyable), but developers need to start thinking outside the ammo box and players need to stop instinctively reaching for their machine gun crutch. No lives were lost when we had to think with portals (although a potato did get shot into space – spoiler alert!). I managed to save my son from the Origami Killer without taking a life. Wouldn't it be better if more major developers weren't afraid to follow suite?

J. Michael Neal is a screenwriter, novelist, and game critic out of Philadelphia, PA. He currently lives in a pineapple under the sea.