Posted in: Books, Comics, Current News, Movies | Tagged: bela lugosi, clover press, dracula, kickstarter

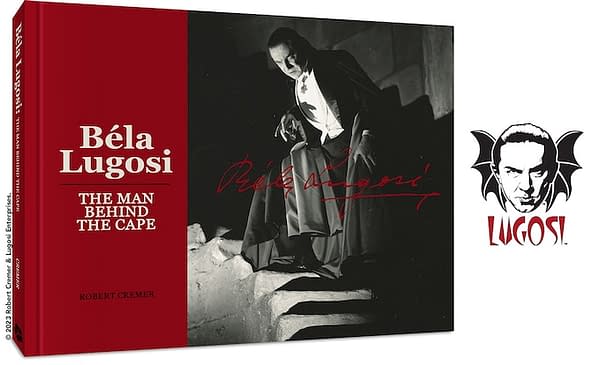

Counting Down to Béla Lugosi's Definitive Biography by Robert Cremer

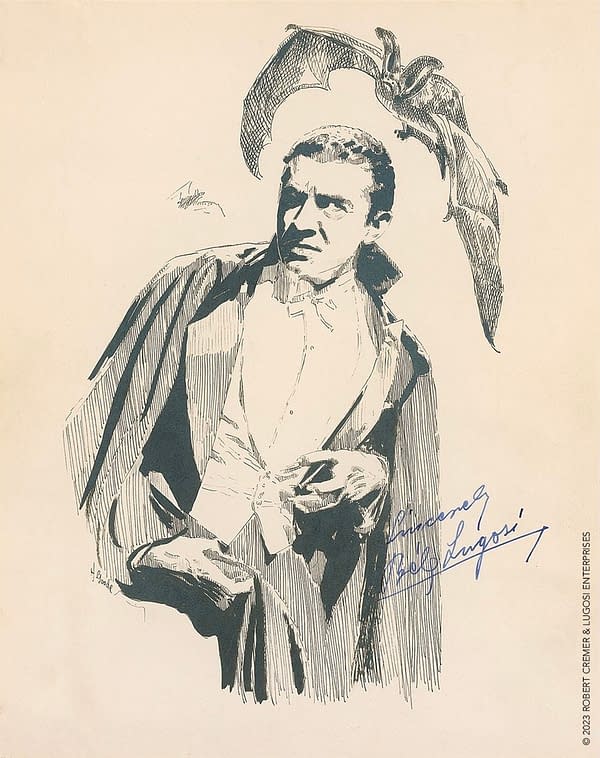

Clover Press is publishing Béla Lugosi: The Definitive Biography by Robert Cremer abouy the actor famed as the quintessential Count Dracula.

Article Summary

- Explore Lugosi's journey from Hungary to Hollywood horror icon.

- Delve into the relationship between Lugosi and filmmaker Ed Wood.

- Uncover Lugosi's struggles with typecasting and his personal demons.

- Get insights from exclusive interviews with Lugosi's family and friends.

Comic book boutique publisher Clover Press is dallying with nonfiction prose by publishing Béla Lugosi: The Definitive Biography by Robert Cremer. Famed as the actor behind Count Dracula, this comprehensive biography follows his own journey from Eastern Europe to America, his struggle to make it in Hollywood, and the demons that haunted him along the way. It features over 700 artefacts and photos from the Lugosi family archives, as a foreword by Bela Lugosi, Jr., an afterword by Lugosi historian Dr Gary Rhodes, and a section on Lugosi's relationship with Ed Wood, with interviews between Cremer and Wood, interviews with Lillian Lugosi Donlevy, Lugosi's wife of 20 years, as well as his closest Hungarian relatives and friends.

It also intends to provide insight into the reasons for Béla Lugosi's decline into B-movie productions in Gower Gulch in the 1950s, with interviews with Edward D. Wood, Jr. with new background on Béla's involvement in the filming of Glen or Glenda, Bride of the Monster and Plan 9 from Outer Space.

The book is being crowdfunded on Kickstarter by Clover Press, and has raised $65,486 against a goal of $10,000 from 387 with just over a day to go. Here are a few bullet points from the book.

- Why Béla enlisted in the army in 1914, when he could have been excused from military service.

- How Béla became a major union organizer in 1918 that catapulted him to fame and then to exile from his beloved Hungary.

- How a sailor and his cat saved Béla's life during his transatlantic crossing to the U.S.

- Why Béla was not the first choice for the role of Count Dracula.

- Why Béla risked involvement in the founding of the Screen Actors Guild in Hollywood, given his near-fatal experience with union activism in Hungary.

- Who was really behind the ban on horror films in 1936.

- Why Béla's film The Raven was a personal nightmare for the actor, despite being a box office hit.

- Why Béla risked his health repeatedly on cross-country barnstorming tours.

- What role fishhead stew played in Béla's embarking on a second career with filmmaker Ed Wood.

- Why Béla asked his son not to drive him to his wedding ceremony with Hope Lininger.

Here is the first chapter, reproduced on Bleeding Cool:

Chapter 1: Lugosi in the Act

Norwich, Connecticut, was a sleepy, summer-stock town with 35,000 residents well off the beaten path of legitimate theater, but that changed dramatically the day that Dracula came to town. Alden Wilkes and Herb Neeter, co-managers of the Norwich Playhouse, pulled the theatrical snafu of the season when they signed Béla Lugosi for a limited engagement in Dracula from August 2 – 7, 1947. Lugosi had often excerpted one scene from the stage play for his vaudeville and personal appearance acts, but his appearance at the Norwich Playhouse marked the second time in two decades that the entire play had been legitimately revived, featuring Béla Lugosi in the starring role.

Booking Béla Lugosi for the play was, in Wilkes' estimation, a shot in the arm that would boost sagging attendance and give his neophyte players the opportunity to work out with a pro, but his optimism was dampened considerably by Neeter's better understanding of the salt and cynicism of New England audiences. Neeter was convinced that a play portraying the supernatural as a reality would find a hostile audience in a predominantly Catholic town, but Wilkes countered with the argument that Lugosi was the man who could pull it off. Little did Wilkes or Neeter know that Norwich would never be the same again.

The usually unhurried pace of rehearsals quickened in anticipation of Lugosi's arrival in late July. Veteran actor Simon Oakland played the intrepid vampire hunter Dr. Abraham van Helsing, and Dick Kiley grappled with the romantic lead, Jonathan Harker.

Oakland's role was by far the most challenging, because he was forced to memorize nearly ninety "sides" of dialogue – theatrical jargon for a single actor's lines and dialogue cues taken out of the play script and written on separate sheets of paper or "sides." Kiley waged his own battle with the priggishly self-assured character of Harker, whose transition from novel to stage to film left it bereft of significant impact on the play. Tempers flared and patience was at a premium as the cast struggled on before Béla's first rehearsal with them.

In an interview with Oakland on the set of Kolchak: The Night Stalker in which Oakland plays a skeptical newspaper editor whose cub reporter is sure a vampire is on the loose in Las Vegas, Oakland immediately recalled those agonizing days in Norwich with the real Count Dracula. "I was a bundle of nerves at first," Oakland noted, "because my part was by far the largest in the play and I wanted to deliver the lines in a way that wouldn't bore the audience or Lugosi. Lugosi was no stranger to me as I knew of him by reputation, but sharing the stage with him was an entirely different story.

I was going to be working with an experienced stage actor who had just 12 sides [i.e. pages of dialogue for each actor] compared to my 90! Who wouldn't get the jitters with that prospect?" he noted with a laugh, still tinged with nervousness after all those years. "At first, I thought it would be far easier to take the role of Count Dracula and give somebody else my 90 sides of dialogue, but I changed my mind during my very first stage rehearsal with Béla. Then," he paused briefly, "I saw that Béla made up for his meager sides of dialogue with a presence you could only describe as spellbinding. He could give you goose bumps by just staring at you. On the stage he moved with a grace that was simply unearthly, uncanny, whatever!"

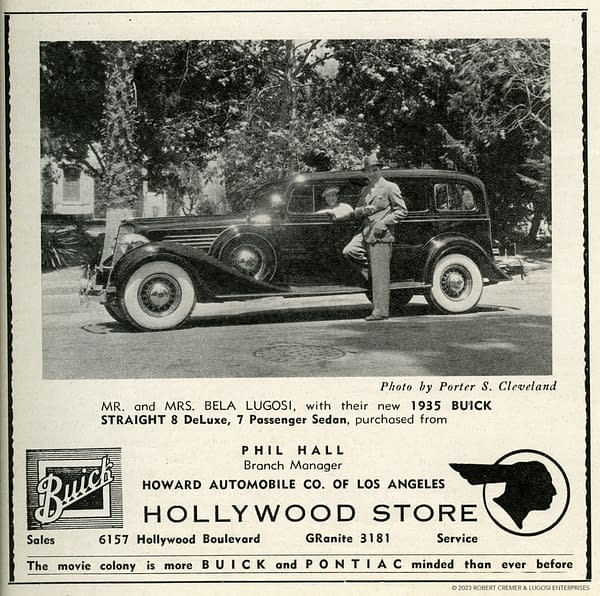

Béla and Lillian Lugosi's black Buick Roadster cruised into Norwich leaving a trail of cigar smoke in its wake. Lillian was behind the wheel, as usual, because Béla had never learned to drive. Producer Ed Wood noted, "The reason why Béla never learned to drive was because he couldn't stand the way other people drove. He said to me, 'Eddie, if I drive a car, I will drive into the backs of other cars and I kill them. And I kill them, too, if they do what I don't like.'"

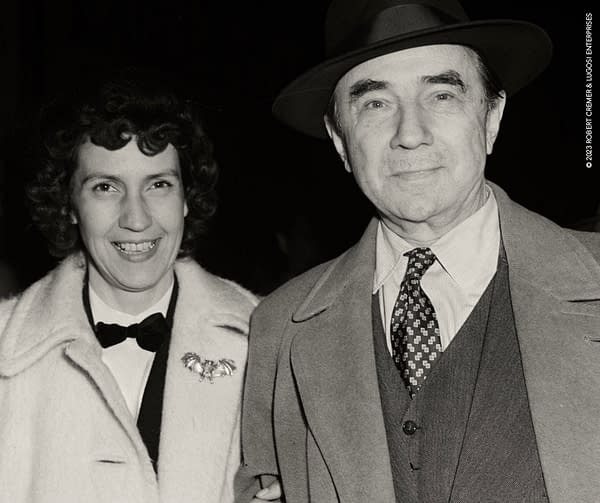

Lillian was sporting a diamond-studded bat pin in her beret – a veritable "good-luck" charm she always wore when they were on the road, while Béla, in shirt sleeves and casual slacks, puffed contentedly on his cigar. As the car rolled to a stop in front of the small theater, Béla jumped out nimbly, met Wilkes, received his rehearsal schedule and the name of the hotel where they would be staying. He assured Alden that he would be able to make it back in the afternoon for a workout with the cast.

At the hotel, Béla lounged in a chair, making notations on the script while Lillian unpacked the suitcases. Lillian suddenly glanced at her watch and said, "Béla, why don't you go over to the theater without me? I can manage the rest of the unpacking, and it's getting late. You'll miss the rehearsal."

"No!" came the curt reply. "You will come to the theater with me. I do not want you to stay here – alone."

"But Béla," Lillian objected, "I haven't written to the family and Bela, Jr., since Newark. Why don't I stay here and get that out of the way? After the rehearsal we can go out and have a nice dinner."

"Lillian," Béla persisted, "you come with me. You can write letters at the theater, but we go to the theater together – now."

Argument, as usual, was futile. It was a scene played and replayed in every city from Miami to Montreal. Both of them knew their "sides" perfectly. Still, Lillian was eternally hopeful that once, just once, she could spend a quiet evening away from the dialogue of the play she knew better than her mother's maiden name. But every passing year only hardened Béla's position; each year he grew more suspicious that a hotel full of solicitous desk clerks, nubile bellboys, and brawny window washers might lure his lovely wife away. He was a legendary actor, true; but he was beginning to show and feel his 65 years.

"I was at my wits' end," Lillian remembered only too vividly. "I never ever gave Béla a reason for being jealous, but you have to realize that he was much older than me and felt his age in certain ways. He could outwork 20-year-olds on the stage, but he was really haunted by the thought that a much younger wife might get ideas, if you know what I mean," she said with a wink. "Béla was not only a perfectionist when it came to his stage and film work, but also in his personal life. I think," she paused thoughtfully, "he was afraid of not being perfect as an older husband. His jealousy aside, he was a wonderful husband and worshiped me, but I couldn't convince him of the fact that I loved him deeply because of who he was – and I kept trying to show him that age made absolutely no difference whatsoever."

Lillian followed Béla dutifully out of the lobby and drove him to the theater for the first rehearsal. When they arrived, Alden Wilkes fluttered around them like a mother hen.

"Is everything to your satisfaction, Mr. Lugosi?"

"Yes, everything is quite satisfactory," Béla replied as he strolled down the center aisle. He was oblivious to the stir he caused among the still rehearsing cast as he made mental notes on acoustics, seat locations, and the distance from balcony to stage. As Wilkes directed him backstage to his dressing room, Béla wheeled around and asked, "Where is the coffin? I must see the coffin!"

Wilkes escorted him to the prop area and pointed proudly to the sleek, enameled black box. Béla ran a loving hand across its top and walked around it slowly, eyeing it like a true connoisseur. Finally, he carefully lifted the lid and lowered himself into the sarcophagus with feline grace. "Fine! This is perfect," he exclaimed, with an expression of contentment that made Wilkes squirm.

Just then, Simon Oakland appeared to inquire about the beginning of the rehearsal, saw Lugosi resting peacefully in the coffin, and froze. "You had to see it to believe it," Oakland noted with a shake of his head. "Lugosi was really at peace in that coffin. It was so uncanny that I could hardly speak. The way he slipped out of the coffin so effortlessly – just like a cat, threw his arm around me and said, 'Simon, it's time to get to work.' I just nodded and walked back to the stage with him." Oakland was beginning to realize that this production would be anything but run-of-the-mill summer stock.

After introductions, Béla went over script changes and chalked out entrances, exits, and positions. As usual, he worked in a sports shirt, paying little attention to atmosphere that was crucial to the play itself. He seemed concerned instead with oiling the egos as well as the performances of the other actors.

"Béla was undoubtedly the most generous actor I have ever met," Oakland remarked. "He was never parsimonious when it came to dispensing advice and his patience was really difficult to understand; most actors of his stature become temperamental and impatient with less-experienced people, but he coached everyone just like a stage director. Everyone in the cast heaved a sigh of relief when they experienced Béla's work style."

The stage director discreetly accepted Béla's suggestions, as he quietly set about remolding the play on the basis of his own experience – the best teacher in matters theatrical. Béla knew which variations from the script worked best as well as when to heighten the drama. Each stage position was blueprinted in his mind, and why not? He had conceived the definitive interpretation on Broadway in the 1920s, embalmed it on celluloid in the 1930s, and resurrected it repeatedly in the 1940s and 1950s.

While Béla revamped the play, Lillian sat in the wings and puffed patiently on Béla's huge cigar. In addition to her chores as chauffeur, wardrobe mistress, and short-order cook during long rehearsals, as well as correspondence secretary on the road tours, she was entrusted with keeping his cigar lit at all times, so that, when he chose, he could swoop into the wings and take a few furtive puffs.

Working with a recognized master of his trade had its drawbacks, however. The cast was tense and stiff in their eagerness to please Béla. During a key scene in the second act, for example, when van Helsing engages Dracula in a battle of wills, Lugosi intoned, "In the past five hundred years, professor, those who have crossed my path have all died, and some unpleasantly." At that point, Béla lifts his arm and beckons hypnotically to the professor to come to him. "Come…here," he commands, while his forearm defies anatomical science and arches from wrist to elbow like a cat's back, vibrating with a life of its own. Van Helsing weakens, then begins to pull himself away from the awesome power of his foe.

During rehearsal the strain got to Oakland, who recalled, "I was supposed to struggle against his will until the very last second and then break the spell by turning away with my hand covering my eyes. When his fingers got to within a few inches of my face, I broke up. I just couldn't help myself. The harder I tried to control myself, the louder I laughed. Pretty soon, we were both laughing and I apologized for ruining the scene. It was so uncanny watching Béla doing his thing in a sports shirt that it was funny. Again, he was very understanding, though I do think that he was a bit perturbed at me."

When Béla arrived on the day of the premiere for a final dress rehearsal, he gasped and stopped dead in his tracks in the lobby. There, opposite the box office, was a replica of his stage coffin flanked by funerary candles and tables laden with quart jars of ersatz plasma. Béla summoned manager Wilkes and asked why such disgusting ploys were being used to attract patrons. The magic of the Lugosi name, he said, should be sufficient to assure success.

At that moment, Teddy, the stage manager, walked in, took one look at the coffin, and exclaimed, "For chrissake, Alden, this is a Catholic town! Hell, the bishop will probably have the play boycotted if word gets around about this."

"Yes," Lugosi chimed in, "it is in poor taste. We don't need things like that to promote the play. Take it away – now."

"I rarely saw Béla so worked up about anything as he was about that coffin in the lobby," Lillian noted. "I knew why, of course, because he was insulted by such gimmicks – as if his name and professional reputation weren't enough to fill the house. Béla was so outraged, in fact, that he was about to call off the performances. God knows we needed the money and I was finally able to calm him down. He did put a real scare into the management, though, and, after that, it was 'Mr. Lugosi this' and 'Mr. Lugosi that'. They handled him with kid gloves!"

Following the rehearsal, Béla retired to his dressing room to prepare for the evening performance. His tuxedo and cape were carefully laid out; his makeup took just a few minutes, because he used only a couple of grease pencil marks between the brows and a faint green facial application. He took painstaking care, however, in his other preparations. Emotionally, Béla felt it was necessary to establish a rapport with his role. Every night, he threw his cape around his shoulders and stood deathly still in front of a full-length mirror. His stare grew so intense that it seemed able to bring the mercury in the mirror to a boil. His entire physique changed in that moment of deep concentration. His chest swelled to twice its normal size, and his jaw jutted out defiantly. Very quietly at first, he intoned, "I am Dracula." He repeated the incantation until his lips were curled in a vicious snarl and he was shouting, "I am Dracula!"

Lillian witnessed this spectacle frequently and commented, "Béla called this ritual ʻcommuning with his character' and he was quite intense about it. When he walked onto the stage, he was not an actor playing a role. No, he was the role. This was his psychological preparation for a performance to remove the boundary between the actor and the role. It was most convincing!"

Then he slowly closed his dressing room and locked it. It was time for an equally chilling ceremony – it was time to "take his medicine" and "lose his pain". "He always wanted to be alone when he took morphine for his pain," Lillian explained. "Since the late 1930s Béla was plagued by sciatica from an old WWI wound that caused severe "shooting" pains in his legs and hips that sometimes left him literally crippled. At first, he tried to deal with the problem with natural health products. You might not believe it," she continued, "but Béla often treated the pains back then by drinking strained asparagus juice! That worked well, until his pains were aggravated by more frequent and far more grueling road tours in the early '40s.

"He was treated the first time around for this pain by a doctor in Los Angeles," she related, "who prescribed morphine. The pains at that time were not as frequent as later, so he only needed the morphine on rare occasion. I should add at this point that he was never addicted to morphine, because I administered the shots when he absolutely needed them. It was a very different story in England, in 1951, when we were there on the Dracula tour," she continued. "Béla had increasing bouts with his sciatic nerve. He went to see a doctor, who prescribed methadone and Demerol which were legal there as painkillers, so he brought them home with him, because he did not want this problem to interfere with his work.

The drugs did work," Lillian explained, "so well, in fact, that he gradually became dependent on them in the early 1950s. Psychologically they also allayed his fear that his pains might strike during a performance. They became his security blanket to ensure that his appearances were never affected by his pains," Lillian said. "He never wanted to let his audience down and did everything possible to make sure he was not struck with pains on the stage. He paid a high price for his obsession with perfection in his career. "

This author would like to note at this point that the foregoing statement by Lillian will be repeated in subsequent chapters of the book. This repetition is intentional on Lillian's part for reasons she explained to this author in numerous interviews. She noted, "Bob, it is very important to me that I set the record straight about his use of drugs. Firstly, he only became psychologically dependent on drugs after our divorce in 1953. Secondly, before that, he was no addict ‒ he was only dependent on drugs to treat severe pains, so that he could continue working. It is important for me that everyone understand the truth, given all the misinformation that was spread around in the press, on TV and, later, even by Béla himself."

The nail-biting repertory players wished each other luck as the curtain rose. Forgotten lines were covered admirably by a nimble prompter, so that by the time van Helsing and Count Dracula meet in their psychological duel in the Second Act, the audience was thoroughly engrossed.

Oakland sensed the audience's mood at that point, and thought it might be interesting to prolong their duel for dramatic effect. When Béla commanded, "Come…here," Oakland fought his power, and fought, and fought. Béla's forearm trembled, but not from satanic power; he threw every ounce of his strength into that arm, and he was visibly exhausted. Back and forth they swayed, titillating the audience until Béla's muscles began to twitch and his snarl sagged appreciably. Teeth clenched, he hissed desperately, "That's enough, damn it! That's enough!" Oakland finally pulled away from him and brought the scene to a climax that earned both actors a round of curtain calls.

After the performance, Wilkes hurried backstage to congratulate the entire cast. Lillian related Béla's conversation with Wilkes:

"Alden, will you please send the coffin to my room?" Béla asked.

"What???" Wilkes replied, scarcely able to believe what he had heard.

"Send the coffin to my hotel room," he repeated. "I want to sleep in it tonight – just until the manager gets us another room. An old war wound, you know. You will see to it that it's brought up tonight? I couldn't bear the thought of another night on that terrible mattress."

"Sure, Mr. Lugosi. Sure," the puzzled Wilkes replied.

"Béla had to sleep on a very firm mattress because of his sciatica and there was no question about that. There were times when a carpenter had to bring a wooden board the size of a mattress to the hotel room to put under the mattress, so that Béla could get a decent night's sleep," Lillian noted. "Norwich was no exception to the rule and one night he did sleep in the stage prop coffin, because his sciatica was quite bad and he wanted, above all, to be sure that the show went on the next evening.

"The coffin had just the right support for his back and hip. The doctor had diagnosed the problem as being in the lumbar region, I think. I never could get used to it, though," Lillian continued. "One time, I remember him climbing into the coffin very carefully and then raising his head and saying to me, 'Lil, don't close the cover, please. I plan to rise in the morning!' I just cracked up," Lillian related with a hearty laugh.

The next morning, hurried arrangements were made to find a suitable mattress for the ailing vampire. The maids reacted most uncomfortably, when Béla emerged from his room, stretched, and remarked, "I never slept better in my life!" As many years as Lillian had been on the tour with him, even she found the make-shift solution for his back problems a bit bizarre. When photographers swarmed into the hotel that morning, clamoring for pictures of Béla sleeping in his coffin, he obliged, but the scene was unnerving for his wife. "It was terrible," she recalled. "Having that coffin smack in front of your eyes was just too much."

Like the hotel employees, local residents who picked up their evening newspaper were never the same again. Standing-room-only crowds formed at the box office every night, breaking house records, but to Béla, Norwich – like so many other successful engagements – was just another town, another hotel, another theater in his endless quest for seasonal work, because the decline in horror-film production beginning in 1936 had left him virtually unemployed in Hollywood. Thousands of miles rolled by on his odometer every summer, now that Broadway offers were a distant memory and prestigious appearances in Boston, Washington, D.C., and Miami had been replaced by a blur of small towns and neglected playhouses.

Though Béla knew that there would always be a place for Dracula on the stage and in audiences' psyches, he began to wonder how long his advancing age could keep pace with his legend. Refusing to admit the limitations of a man past retirement age, he drove himself relentlessly, half-convinced that he shared Dracula's immortality. World War I injuries suffered on the Eastern Front, chronic ulcers, and increasingly frequent bouts of sciatica sapped his strength as he neared his seventieth year, but he pursued his messianic mission nonetheless. Psychological stress and physical infirmities worked in tandem to reduce the stately actor to a state of nervous exhaustion and emotional collapse.

His decline gained momentum during the 1950s when his wife of twenty years divorced him and took custody of their only child. "The divorce broke my heart," Lillian related with a halting voice. "I didn't want to leave Béla, because I knew at that point that he needed me more than ever, but the depressions and emotional outbreaks because of his professional frustrations grew so overbearing that I also had to think of our son, Bela, Jr.," she explained. "I wasn't taking the easy way out," she sobbed. "I was taking the only way out."

Producers lectured Béla on the facts of life: His films were out of vogue and his style outdated; the world had changed drastically with the explosion of the atomic bomb. His friends pleaded with Béla to get a grip on himself. Béla was no stranger to adversity, but the current situation presented a cluster of crises that Béla was not able to cope with, either psychologically or physically. It wasn't until he reached the brink in March, 1955, that he picked up the phone and made the call that saved his life.