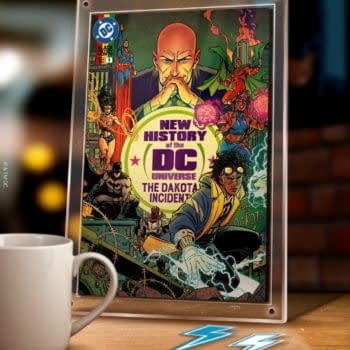

Posted in: Comics, Recent Updates | Tagged: animal man, Comics, dc comics, entertainment, grant morrison

Deconstructing Morrison Part 1: Animal Man And Black And White Morality

By Adam X. Smith

After fellow writer Joe Colewood and I did a piece discussing the merits of Grant Morrison's Multiversity #1, it dawned on me that I was nowhere near as qualified to critique Grant Morrison's work as I had initially thought. As a result, I've decided it's high time I give some works of his that I've not yet read – and some that I have – a reappraisal. This week, I start at the beginning with his first work with DC Comics, Animal Man. *Heavy spoilers below, naturally.

Let's imagine for a moment that you live in some sort of bubble dimension where you've never read or heard of any of Grant Morrison's work, and your only knowledge of the character Animal Man is that he's the subject of a series of funny videos on DC Nation. In that event, imagine what you would make of a series in which he becomes a vegetarian animal rights protester whose adventures include:

- Saving a pod of dolphins from Faroe Islanders.

- Preventing the detonation of a doomsday weapon during the Thanagarian invasion of Earth.

- Joining Justice League Europe just in time for a plot device gene bomb to render his powers ineffectual.

- Fighting an immortal African dictator and apartheid thugs in Africa.

- Tripping on peyote in the desert and becoming aware of the reading audience watching him from an alternate plane.

- Encountering the likes of Mirror Master, Psycho Pirate, the aliens that gave him his powers, the Time Commander, a legion of characters deleted from continuity during the events of Crisis on Infinite Earths, and finally Morrison himself.

It's quite a big pill to swallow, as it turns out, but I had to start somewhere.

So anyway…

The principle reason I read Morrison's run on Animal Man was so that I could finally determine whether or not to believe the hype regarding Morrison's work and its much-touted preoccupations with the Multiverse and leaning on the fourth wall. And credit where it's due, the places where Animal Man seems to be most effective is when it dabbles with Morrison's interests in meta-fiction and social activism, particularly #5's "The Coyote Gospel", in which Animal Man encounters a peculiar looking, functionally immortal man-sized expy of Wile E. Coyote in the desert.

However, my enjoyment of Animal Man does come with a few caveats, the first of which is that the dynamic between Buddy Baker (Animal Man's civilian identity) and his family is a little tin-eared for my taste. Considering how Morrison has essentially created a (post-)nuclear family to act as motivation for him, they rarely get much character development asides from when it suits the narrative: his wife Ellen is a storyboard artist who wants to sell a children's book and doesn't really get a lot else to do besides idly fret and roll her eyes at Buddy's antics, his nine-year old son is an obnoxious little git with a mullet who everyone picks on and yet remains completely unsympathetic, and his five-year old daughter is an adorable little imbecile who does hardly anything to further the plot apart from encountering a ghostly apparition of Animal Man that only makes sense a lot later in the series. My colleagues have told me that this aspect of the series is developed much more under subsequent writers, which is fine, but it doesn't make Morrison's creation and utilisation of them any better.

Even Buddy's actions and motivations as a parent are incredibly dubious in a sort of inverse Homer Simpson-esque way: he impulsively decides that the family is going vegetarian without even consulting his wife; he has JLE security measures installed in the house without realising his son is coming home from school alone and might set them off; he is absent as a husband and parent for protracted periods of time without seeming to bother to stay in touch with his family; he lets Martian Manhunter terrify his son's bullies instead of dealing with them himself like an adult; his wife is threatened with rape in an early issue and no attempt is made to follow up on this potentially traumatic event whatsoever, least of all by Buddy himself; and in a move that almost put me off the book, his brazen lack of a secret identity and his increasingly high-profile and questionable associations with eco-terrorists plays a direct role in his family getting fridged by an assassin. The reason this inspired in me annoyance rather than sympathy is because we aren't being asked to feel sorry for his dead family but to feel sorry for the asshole who got them killed with his negligent parenting, superhero show-boating and damn-fool bleeding heart liberalism.

Don't let me be misunderstood – I have nothing against vegetarianism or animal rights activism. I have nothing but respect for vegetarians and vegans, because I know that however much I might consider it a noble cause to take up, I'd never hack it as one. It's less to do with the content and concepts, and a lot more to do with the way it's integrated and conveyed in the narrative.

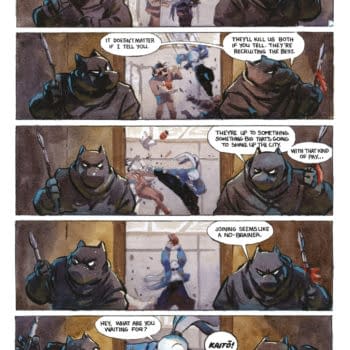

Making such issues as animal testing, the plight of dolphins and marine mammals, biological weapons testing and apartheid central to the plot of a series that's nominally about a guy who can absorb animal powers in a manner that doesn't always make incredible sense is all well and good, but it's undercut by how black and white the morality is portrayed. Almost all the villains, whether they're S.T.A.R. Labs scientists testing anthrax on apes, redneck attempted-rapist hunters, dolphin and whale-hunting Faroe Islanders or corrupt government officials, are portrayed as cartoony arseholes who don't give a shit about anything other than hurting, maiming and killing animals and therefore deserve everything they get.

The fact that Morrison later decided to show the supposed consequences of Buddy's less than stellar judgement – his involvement in a raid of a testing lab (and one of the activists setting it on fire for some reason) results in the death of a firemen – and the increasing criticism of the preachy self-righteousness of his activism didn't really change the fact that the villains never really gain any additional complexity – they're still assholes who deserve it. It would have had more resonance if Buddy ever actually seems to learn anything from his mistakes or to take responsibility for them, but this never happens. If any lesson is learned at all, it's some old chestnut about "life is its own reward", and while it's left unclear in the end whether or not Buddy remembers the events that have occurred, it's questionable whether he's got it together enough to effect change anyway.

No matter what revelations are made to him about his origins or the nature of the (DC) universe, he never truly manages to gain anything from it. Even after borrowing a time machine and getting hurled backwards through his own timeline (in a move that will be familiar to anyone who remembers Matt Smith's tenure on Doctor Who , *wink wink, nudge nudge*), finding himself in the comic-book equivalent of Purgatory and then meeting Morrison, he's demonstrated to be completely lacking in any real agency, and this extends to all the characters in the story – a lampshade is hung on the fact that characters only seem to exist when they push the narrative forward. That kind of solipsist attitude seems really deep when you're a broody teen going through the existential angst of adolescence (I should know – I've been one of those broody teens), but aside from being self-deluding it leaves the door open for lazy writing.

In fact, the whole piece carries a spectral air of anti-climax – Morrison's avatar point out that he has a habit of writing stories that build up to a denouement that never happens. He also gets in a few jabs at the idea of "realistic" comics while he's at it, for what seems like justification for doing the exact same thing by way of satire (when on his mission to avenge his family, Buddy starts wearing a leather jacket and shaves his head in a way that reminds him and the audience of Travis Bickle from Taxi Driver by way of the Punisher). And it is ultimately on Morrison's whim that the Baker family gets un-fridged and Buddy's status quo is reset just in time for a new writer to take over.

I'm not saying that Animal Man is bad on this basis – its very existence is testament to the adage that you can make a good story out of anything. However there is an inconsistency present in its tone and execution that is unmistakeable – call it hedging one's bets, or first mainstream gig skittishness, or the desire to please the maximum amount of people – and however much it might be typical of Morrison's later output it owes more than a little to the works of his many contemporaries. But considering that it is on the basis of this run among others that he has built a career and loyal following, I'm more inclined to forgive teething problems with him here than anywhere else.

Adam X. Smith is a paranoid android from the Planet X. For the last 27 years he has been living amongst the people of Birmingham, England (and more recently the University of Lincoln) ostensibly as a student of the school of hard knocks (also BA Hons Drama), but secretly on a mission to scout out the planet for invasion by alien forces; his weekly communiques on his various blogs are actually highly coded messages to his extra-terrestrial masters. He enjoys the musical stylings of local chiptune-metal band Elmo Sexwhistle, the fiction of Kim Newman, Kurt Vonnegut and Chuck Palahniuk, and his hobbies and interests include film-making, drama, occasional Youtubing, journalism and plotting the subjugation of humanity. He can be found on Youtube, Tumblr, Twitter or by jamming an ice-pick through the optic chiasm.