Posted in: Comics | Tagged: Comics, entertainment, fox, Marvel Comics, marvel entertainment, Secret Wars, wolverine, x-men

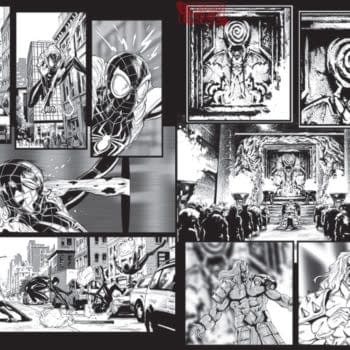

Reed Richards Meets Leon Trotsky: Remembering Secret Wars

Brian M. Puaca writes for Bleeding Cool:

Remember Leon Trotsky? No? Not really? Well, the odds are pretty good that many of the young Soviets growing up in the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s didn't remember him either. Many may well have never come to learn of his existence at all. The reason? Joseph Stalin systematically sought to remove him from the collective memory of the Soviet population after he came to power. While there were a variety of methods to achieve this goal, the most visible example of this policy was the airbrushing of the Red Army leader from photos taken during and immediately after the Russian Revolution.

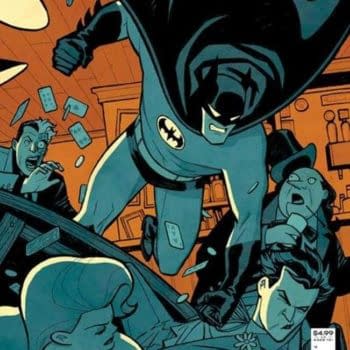

Is it fair for Marvel to do this? Sure, it is. These are Marvel products and the company is free to do with them what they wish. The goal, of course, is to maximize profit. Someone who makes marketing decisions clearly decided that uniting a popular historic series (one that is, not incidentally, seeing its title used again this summer at least in part as a nostalgia ploy) with the current hot properties of the Marvel Universe made good sense. One can almost hear the word "synergy" being used in a corporate meeting to explain the way the past and present are being united — and manipulated — for selling merchandise.

Is it a good idea for Marvel to do this? That is a different question altogether. Judging from the products that have so far popped up with this, ahem, revised version of the Secret Wars covers, one can assume that they are being marketed at adults familiar with the original series. Or better yet, they are being sold to those unfamiliar with the actual books who are buying them for fathers, husbands, uncles, or sons. Therefore, it is safe to assume that the target audience for these products are those who have a personal recollection of the original books. Again, Marvel is likely playing on a sense of nostalgia for the Secret Wars series of the 1980s that are remembered fondly by many in their thirties and forties.

So is there a bigger effect of this clear manipulation of the past for present and future commercial purposes? Maybe. Some consumers might not give it another thought. Others, however, might find it to be a crass commercial decision that makes a lasting impression. This is not merely an example of a screenwriter taking liberties with a character or storyline for the silver screen. It isn't a question of interpretation. Instead, this is literally the manipulation of the past, and specifically the iconic art of some of the most popular comic books of the 1980s, for profit. This may well irk many of those who recognize the changes and consider their purpose.

In thinking about this even further, it is fascinating to consider the fundamental underlying tension here between nostalgia for a distant comics past and contemporary financial considerations. Marvel is banking (pun intended) on the fact that the images are instantly recognizable to its target audience. Likewise, they presume that these images will be remembered fondly by those who know them and will appeal to them in the store or online. Yet there is also the hope that the images won't be remembered too completely, as this might stop one from making the purchase. Worse still, it could frustrate or anger a fan who is precisely the same person likely going to Marvel movies, streaming Daredevil on Netflix, and/or buying Marvel Unlimited subscriptions.

Admittedly, this would be a forceful (and unlikely) response from fans. But as many political elites have learned the hard way, the long-term effects of manipulating memory can be highly unpredictable. At the very least, when the collective memory is altered in such an obvious and heavy-handed way, it usually reveals the true interests of those pulling the strings. So, too, does it in this case. These instances — and one can hardly doubt there are more to come — underscore Marvel's willingness to dispense with the past in order to make a quick profit.

Brian M. Puaca is an associate professor of history at Christopher Newport University in Newport News, Virginia, where he teaches a course on the history of comic books and American society. He can be reached at bpuaca@cnu.edu.