Posted in: Comics | Tagged: Craig Yoe, great moon hoax, idw, robert grossman

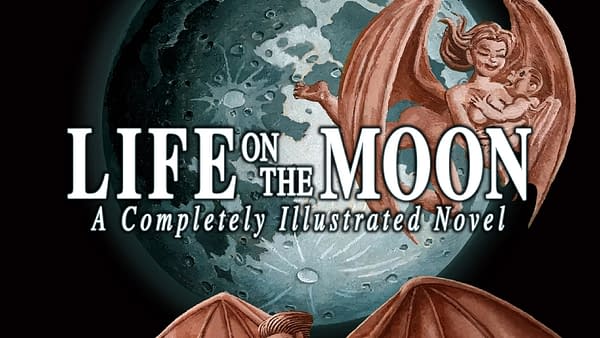

Going Antiviral: Robert Grossman's "Life on the Moon"

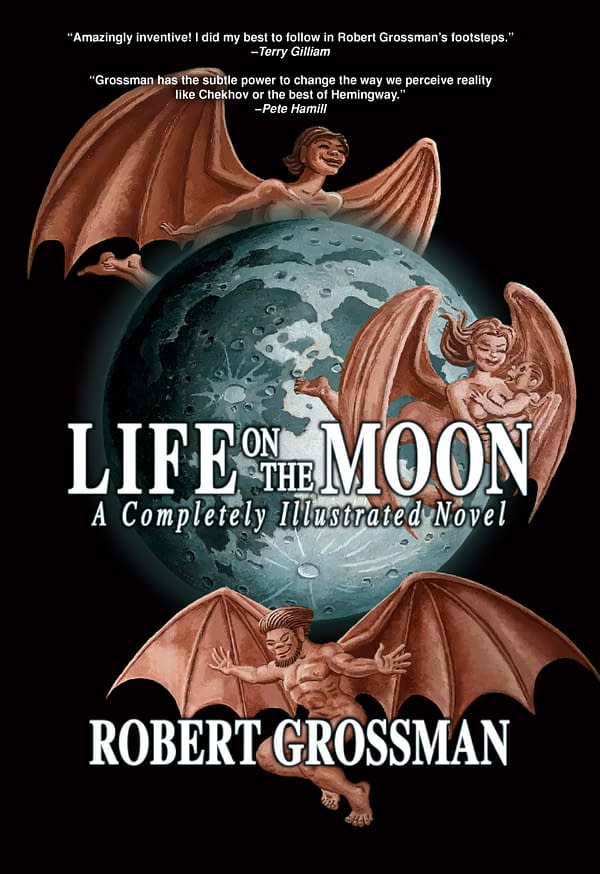

Robert Grossman's Life on the Moon takes the history of the Great Moon Hoax and does something completely unexpected with it.

"From the moment when living organisms appeared in the seas billions of years ago, they seemed driven by an instinctive urge to move beyond their own environment. Out of the dark waters they groped across aeons, toward the light and land and air."

—Time Magazine, December 6, 1968

"When "Comrade" Nixon finally emerged from the Svengali job thrown on him by the smirking, beetle-browed Brezhnev, lo! we had given those bombastic bums nuclear superiority, the Mediterranean, tiny enslaved Chile, and the Moon — just as surely as if the title to all this real estate had been signed in the very lifeblood of the men, women, and children living on it."

—D.L., R. Schultz, National Lampoon, August 1972

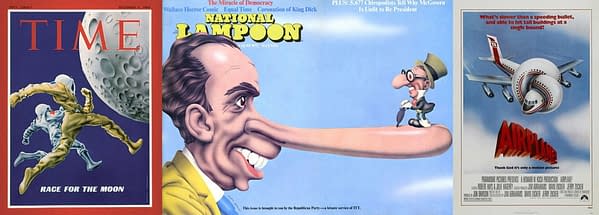

You know Robert Grossman's work even if you don't know his name. Remember that tied-in-a-knot jet on the movie poster for Airplane!? That's Grossman's work. Then there's the August 1972 National Lampoon cover spread of President Richard Nixon as Pinocchio.

Beyond that, there's covers on a stunning range of magazines from politically subversive 1960s/70s publications like Ramparts and The Realist, to Rolling Stone, to that firmly mainstream December 6, 1968 Time Magazine cover depicting the Race for the Moon.

Looking back on the scope of his body of work, particularly his magazine covers, I'm struck by the political and cultural range of it. The art editor of Ramparts does not typically seek out an artist who has an iconic Time Magazine cover on his resume. The art editor of Newsweek does not typically seek out an artist who has done covers for the late Paul Krasner's The Realist — a man whom an FBI agent was once assigned to write a letter calling him "a raving, unconfined nut" in response to a Life Magazine feature.

Somehow, Grossman's work spoke to everyone.

It might be the almost supernatural clarity he brought to his art. That Airplane! poster art, for example… one look tells you exactly what you need to know. A textbook definition of iconic.

Likewise, Grossman's Time Magazine Race for the Moon painting captures that moment so well — and perhaps even better than he understood. Behind the scenes, NASA and the CIA were apparently a maelstrom of spy intrigue and gutsy decisions. Time rival Newsweek actually had an alternative cover prepared in the event of the failure of the Apollo 8 mission.

A Ben Day at the Races

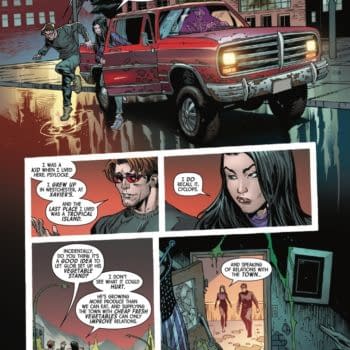

The type of history covered in Grossman's Life on the Moon (available everywhere now, from Yoe Books and IDW) is directly in my wheelhouse. Not only do I love history, but as a collector of American periodicals, this particular history is a favorite of mine. Every moment of this weird bit of history contains a wealth of fascinating historical facts.

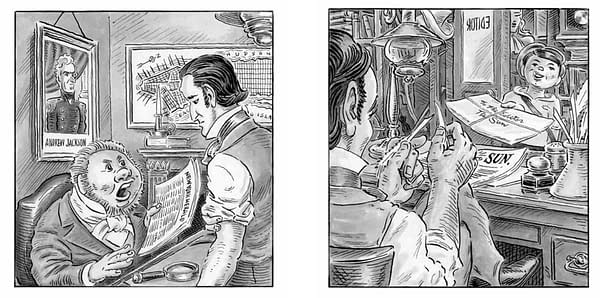

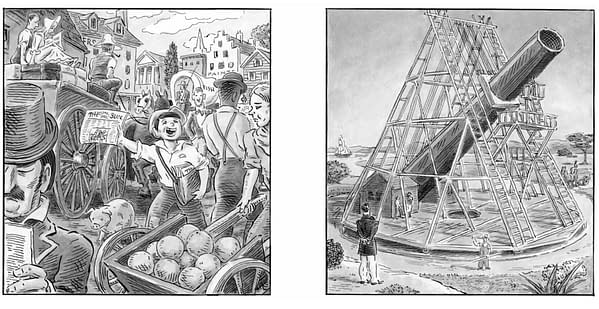

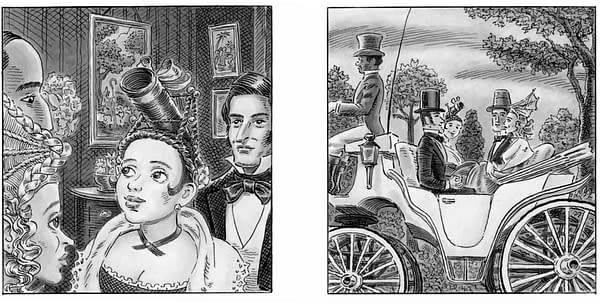

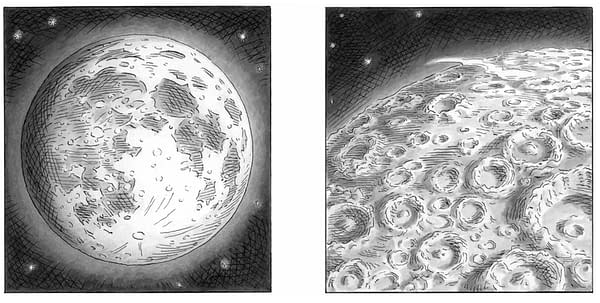

In brief: in 1835, Benjamin Day's New York penny paper The Sun launched a series of news releases purported to be an account of discoveries made by one of the most famous astronomers of the era, Sir John Herschel. An accomplished mathematician and inventor as well, Herschel traveled to South Africa and built a 20-foot telescope to catalog the objects of the southern skies in 1834. In a series of articles in The Sun purported to have been written by Richard Adams Locke, it was revealed that Herschel had discovered… Batmen on the Moon. Of course, this was a hoax.

It's often overlooked in discussing the actual history behind the Great Moon Hoax that this is merely one example of The Sun publisher Benjamin Day's appetite for success. He also helped launch the important illustrated paper Brother Jonathan (and in particular, the mammoth-sized Brother Jonathan editions are spectacular examples of historical comic art). His Brother Jonathan Extra editions were among the first cheap mass-market complete-story fiction collections in this country. Brother Jonathan Extra #9 was also the first comic book published in the United States. His son, Benjamin Day Jr, invented Ben Day dots, which became a popular process for creating secondary colors and color tones on newsprint for periodicals such as comic books.

That notion of Ben Day's drive for success brings to mind another underlying (and understudied) reason that makes the Great Moon Hoax such fascinating history. It's an early example of viral news at a mass scale. Many of Day's rivals picked up the news — and further, some elaborated on it, as if they had unearthed additional facts — and repeated it without independent verification. This was much more common in the 19th century than people understand, and in fact some of the largest, most trusted names in the history of American news got their starts repeating and remixing other people's news as if it was their own. It's far from a modern phenomenon.

At the other end of the spectrum — as I've mentioned here before — is another wonderful bit of trivia connected to the Great Moon Hoax: Julius Schwartz wrote an article about it in the January 1934 issue of his fanzine Fantasy Magazine. Long before he became the editor of Batman or the co-creator of Man-Bat. I often wonder if the course of one of the most important fictional characters of modern times was influenced just a tiny bit by those fake Batmen on the Moon.

Meanwhile, speaking of scientific hoaxes: one of Schwartz's best friends and a contributor to that very same fanzine, Raymond Palmer (yep, the Silver Age Atom is named after him) played a significant role, according to his FBI file, in turning UFOs into a phenomenon in the wake of Roswell and other incidents. It seems pretty likely that Palmer also took some inspiration from the Great Moon Hoax.

As fascinating as I find this underlying history, I let this book sit in my head for a while before I decided what I thought of it.

It's not really what I expected, at all. It's different, and far more clever.

This isn't some straightforward retelling of some obscure yet fascinating bit of history. It's the kind of work I should have expected from an artist who can speak to the Time Magazine audience and the Ramparts audience at the same time.

It's rather devious. It forces you to think.

Here's the thing: our perception of history is fluid, and is way harder to get right… completely right… than people realize. New information emerges (particularly these days as digital archives come online and are made available) and interpretations change based on added context. History is necessarily revisited all the time.

A straight retelling of a historical incident is almost certain to get stuff wrong. I wonder if that's why Grossman ended up leaning into the fake news aspect of this story, by creating a book that itself… hoaxes the hoax.

Race for the Moon Pies

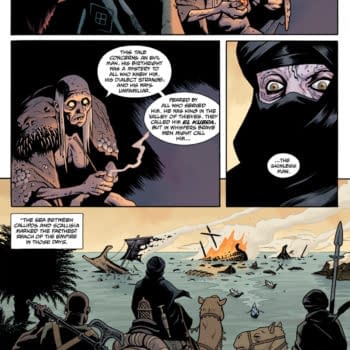

It won't take you too long after you start reading Life on the Moon to understand that something is not quite right. Grossman has remixed his hoax history into something else entirely.

I'll explain by way of example. There's almost a throw-away moment in Life on the Moon during which the hoopla that the Great Moon Hoax generates is said to have inspired everything from elaborate hair styles, to that chocolate wonder we know as the Moon Pie.

This is untrue. In his afterward explaining what he'd done with the history in this book, Grossman says that he wasn't sure exactly when the Moon Pie was invented. Because I love researching history, I can't resist seeing if I can figure it out. The official company lore of the makers of Moon Pies, explains it exactly like this:

It all began in 1917 when a KY coal miner asked our traveling salesman for a snack "as big as the moon." Earl Mitchell reported back and the bakery obliged with a tasty treat aptly named MoonPie. It was filling, fit in the lunch pail and the coal miners loved it. The rest, as they say, is history.

Sorry MoonPie, you certainly are delicious, but this sounds like history written by a marketing department, with perhaps a little bit of truth baked inside. And of course, that's fine. This is hardly the Watergate incident I'm investigating here. But let's take Robert Grossman's lead here and see where this goes.

A look at The Great American Moon Pie Handbook from 1985 confirms my suspicions, sadly. Noting the cooperation of the Chattanooga Bakery, Inc, creators of the MoonPie, author William Clark says he has received his historical information from John Kosik, Executive Vice President of the firm.

In this version, a traveling salesman walked through the door of the Chattanooga Bakery itself in 1919. Seemingly not satisfied with any of the cakes or cookies he sees on display, he describes a wonderful baked treat that we now know as the MoonPie.

"The name of that traveling visionary has been lost to the ages, but his idea lives as a testimonial to truth, justice, and the American way," says the Moon Pie Handbook.

Tsk.

In 2007, the book MoonPie: Biography of an Out-of-this-World Snack attempts to revise this history. Waving off the 1985 version of the story as satire mixed with fact, author David Magee explains that the publicity accompanying that previous book brought forth the real story — which is basically the version that exists on the company website today. Magee goes on to explain how that played out in newspapers of the era.

This gets us closer to the truth, but perhaps not quite all the way there. In 1987, the Associated Press released a widely syndicated article about Earl Mitchell's family coming forward with the backstory. However, the creation date has reverted to 1919 in this account. The AP's MoonPie investigator is not to be confused with an infamous New York Times White House reporter of the same name, by the way, although one can only imagine what Grossman might have done with such a delicious coincidence. The AP report triggered MoonPie investigations from various news outlets, and brought forth various conflicting details, with Chattanooga Bakery president Sam Campbell IV only addressing the history in a relatively vague way and not really speaking much about the early years of the matter.

So much for official corporate sources. Let's see what else we've got.

U.S. Census data confirms that Earl Mitchell was indeed a traveling salesman for a bakery in Chattanooga in 1920 (and likely before). That syncs up with the Mitchell family story pretty well.

However, the MOON PIE trademark was filed by Chattanooga Bakery in 1955, and the paperwork claims first use on 1917-01-01. The 38 year gap and the January 1 date might possibly suggest they're not exactly sure, but that would certainly put the date of the creation legend in 1916 at the latest, regardless.

It's likely no coincidence that MoonPie newspaper advertising likewise turns on like a light in 1955 — with essentially none to be found before that date, despite regular Chattanooga Bakery newspaper advertising of other items in the decades prior. This is not to say that the MoonPie wasn't actually invented in 1917 (or 1916, 1918, or 1919) like the company says, but… I'm a little skeptical, absent further evidence.

Dark Side of the Moon

Bringing this neatly full circle, the mid-1950s were indeed the era during which the American public started thinking about Life on the Moon in earnest. Disney opened Tomorrowland with its Flight to the Moon attraction in 1955. The same year, Disney also televised a Man and the Moon special featuring none other than Werner von Braun. Long story short, von Braun — the best-known creator of the dreaded German V2 rocket, one of the most fearsome weapons in the Nazi arsenal during WWII — was helping explain and promote concepts of space flight to the American public with Disney's help. And among other environs, the Moon was our destination.

Just as it was in 1835, the Moon as an object of our fascination was ascendant in 1955, with films, songs, newspaper headlines — and a tasty treat called the MoonPie, freshly trademarked and now being heavily advertised. The space race was getting underway.

Robert Grossman died on March 15, 2018. I'd have liked to have shown him my completely unserious MoonPie investigation above, because I suspect he'd have been over the moon himself to discover that the thing that launched the MoonPie into national fame was likely the same Race for the Moon that helped launch his own career. But probably not all that surprised.

Because I think I finally see why he considered Life on the Moon one of his greatest achievements. He wasn't creating a story about history that would be read and casually tossed back on the shelf and forgotten. He was creating a story that would make you look again and again. A story that might make you think and ask questions. It's a story that doesn't exactly retell history — but explains it, by way of example.

Fifty years after his Race to the Moon, Grossman's Life on the Moon is an important reminder to always verify the sources yourself.

Even in fiction.

Life on the Moon is available now in stores everywhere.