Posted in: Comics, Vintage Paper | Tagged:

The Tariff Dispute That Chronicled the End of Mr. Monster and Nelvana

In 1947, U.S. customs categorized the last Golden Age appearance of Nelvana & Mr. Monster as a pamphlet, resulting in tariff charge, and a court proceeding that tells us about this unusual release.

Article Summary

- Nelvana and Mr Monster mark their final Golden Age appearances amid a perplexing tariff dispute in 1947.

- Frank E. Howard's ambitious plan of reprinting Bell titles falters amidst strict U.S. customs scrutiny.

- Court testimonies expose shifting market strategies and confusing publication practices with Super Duper Comics #3.

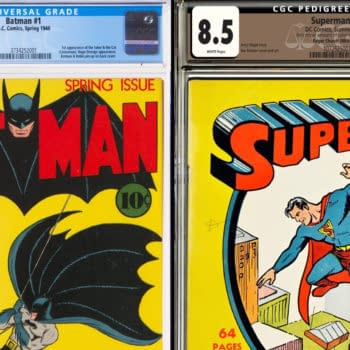

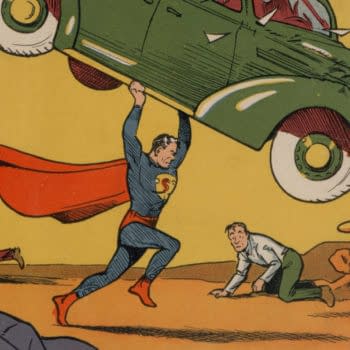

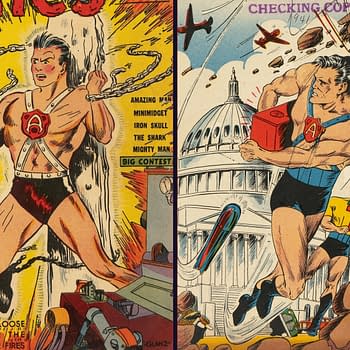

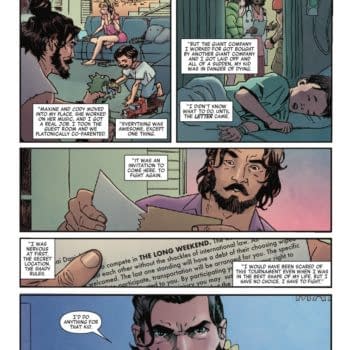

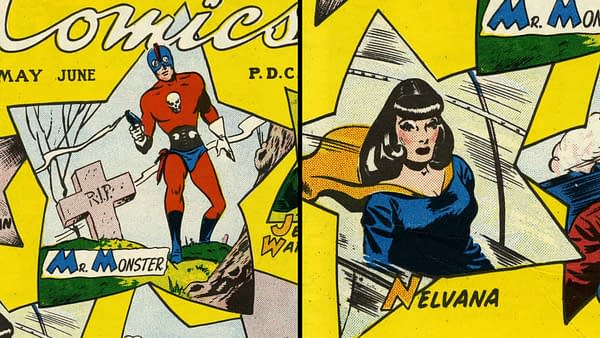

Super Duper Comics #3 (F.E. Howard, 1947) is best remembered by comic book collectors today as being one of only two Golden Age appearances of Mr. Monster. Created by Fred Kelly, the character began life as Doc Stearn in Bell Features' Wow Comics #26, running through Wow Comics #30, next appearing in Commando Comics #22, and then becoming Mr. Monster in the final panel of Triumph Comics #31. Famously, creator Michael T. Gilbert stumbled across a copy of Super Duper Comics #3 sometime in the 1970s and was inspired to revive the character. Gilbert's Mr. Monster debuted in Pacific Comics' Vanguard Illustrated #7 (cover dated July 1984), and has appeared in a number of mini-series and specials in the decades since. Super Duper Comics #3 is also notable for being the last Golden Age appearance of the legendary Canadian superhero character Nelvana. Created by Adrian Dingle, Nelvana first appeared in Triumph-Adventure Comics #1, running through Triumph Comics #31, and was also featured in the now-iconic 1945 Nelvana of the Northern Lights one-shot.

Several of Bell's original core 1941/1942 titles, including Wow Comics, Commando Comics, Triumph Comics, and others, ended in 1946. Active Comics and Dime Comics were later briefly revived as color reprint series. After issue #31, Triumph Comics had an odd additional 1946 issue called New Triumph Comics, which was Chesler Punch Comics color reprints, and was also later revived as a color reprint series. It has been noted by historian Ivan Kocmarek that several of the features that ended with those titles in 1946 contained notices that they would continue in full color. But this did not happen as planned. As explained in John Bell's Invaders from the North: How Canada Conquered the Comic Book Universe, "As the war neared its end, Cy Bell borrowed $75,000 and purchased a huge offset press from the Cleveland Plain Dealer. Determined not to be displaced by the influx of American comics, he issued two colour comic books in 1946, Dizzy Don Comics and Slam-Bang, and planned for an ambitious line of new titles. He also began to arrange for distribution not only in the United States, but in the United Kingdom, as well. Bell apparently encountered a major obstacle, however, when the federal government refused to authorize the purchase of newsprint in the quantities that his company required. Deterred by this and other problems, Bell Features ceased publishing its own titles and began reprinting U.S. comics for the Canadian and British markets."

Nelvana, Mr. Monster, and other features that had been slated to continue in color eventually did so for one final time in the Golden Age, not from Bell Features, but in F.E. Howard Publications' Super Duper Comics #3. Frank E. Howard had big plans for the title. Using Cy Bell's strategy of pushing into the U.S. market with Bell characters and even using Bell's printing press, Howard made a significant financial bet that he could succeed where Bell had failed. The United States Customs Court case Carey & Skinner, Inc. (an import broker) v United States chronicles what happened here, with descriptions of testimony from Howard and Cy Bell. As explained in the document, Bell's role here was as representative of Rotary Litho Co., Ltd., the printer of Super Duper Comics #3. Kocmarek has some excellent background on this company, which was set up with the expectation that they would take on other clients after purchasing their large color press. At issue in the case was a shipment of 328,965 copies of Super Duper Comics #3, which customs officials classified as pamphlets rather than periodicals, and per the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930, assessed a 7.5% duty on the shipment rather than allow it free entry, as periodicals would normally receive.

To unpack Howard's testimony in terms of his explanations about the first two issues of Super Duper Comics requires some context of the rapidly evolving international trade policy of the post-WW2 era. We've already explained the end of Canada's War Exchange Conservation Act Section One on August 1, 1944. But UK trade policy subsequently comes into play in this case. With the UK attempting to restart and rebuild much of their industry and their economy directly after WWII, on September 24, 1945 they instituted a ban on non-essential imports from the U.S., and continued to heavily restrict U.S. imports through much of 1946. Heavy restrictions on imports from Canada and Australia were also put into place, easing in the early months of 1946, but still with some limits throughout that year. Restrictions on imports from the U.S. to the UK began to ease in late 1946, and several countries attempted to normalize international trade with the 1947 General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (although as we have seen, this did not prevent Canada from banning the import of printed U.S. comics with FECA later that year).

As was the case with WECA, the UK restrictions on U.S. imports also included materials that could be used to reprint comic books. This resulted in a brief window in 1946 during which UK publishers could not reprint U.S. material, but Canadian publishers could license U.S. comic book material and export those comics to the UK. One method of doing this was to print these comics with a normal cover for distribution in Canada but with a 6-pence price printed on the first page of the comic book. Coverless copies were then shipped to the UK.

Changing trade policy gave rise to a number of comic books published in Canada in 1946 also meant for export to the UK. Given relatively small print runs that were split between Canada and UK release, and UK versions which are coverless and less likely to be correctly identified (if they survived at all), these 1946 releases are surprisingly little-documented, and still being discovered today. While GCD tentatively identifies Super Duper Comics #3 as continuing the numbering of surrogate-published Latest Comics, the issues described in court documents here do not match those details. Super Duper Comics #1 is described as an October 1945 release with black and white interiors, while issue #2 is explained as a hybrid Canada/UK release in full color, with a normal cover in Canada and shipped coverless to the UK. It's unclear whether this was an undocumented Canada/UK release from that brief 1946 window, or if this was subterfuge on Howard's part to attempt to explain that Super Duper Comics #3 was part of a series. The actual content of what was identified as the first two issues of the series was never addressed here.

It's clear that the judge found Howard's explanations on this front confusing. He noted that a coverless comic book which did not bear the Super Duper Comics title had been submitted into evidence as issue #2 of the series ("A copy of this second edition, minus cover, is in evidence"). The court also took note of other inconsistencies in Howard's testimony: "From an examination of the instant record, which contains inconsistencies and contradictory evidence, the following facts emerge: For the period from October 1945 to about August 1946, F.E. Howard Publications, Ltd., put out a monthly magazine, presumably under the title of Super Duper Comics, consisting of black-and-white comics with a four-color cover. The 35,000 copies of each edition were distributed partly in the UK, partly in Canada. The Canadian copies, unlike those shipped to the United Kingdom, contained covers and bore the respective dates of issue. In June 1946, the first full four-color edition was published, and, as in the case of the monthly series, was distributed in Canada and in Great Britain, with the Canadian copies containing both a cover and an issue date. Furthermore, there were indications on the cover page to the effect that Super Duper Comics in four colors would thenceforth be published on a bimonthly basis."

The court decision document then moves on to Howard's reasons for not adhering to a bimonthly schedule. Super Duper Comics #3 was shipped to the U.S. in April 1947, around seven months after the stated release date of issue #2. While it can be historically supported that comic book publishers had lingering issues in obtaining paper well after the war, and certainly into 1947, the judge was troubled that Howard undercut part of his own testimony by suggesting otherwise, noting that "witness Howard freely admitted that his allotment of one carload of paper per month was adequate for printing 350,000 copies." Howard nevertheless explained, "The delay was trying to get the thing rolling for American distribution too and trying to conserve as much paper for me to use for the American, because there is a big difference between printing 30,000 and 350,000. Because I had to find suitable artwork for American distribution. And the quantity was so increased, from 35,000 to 350,000, I had to find sufficient paper. I had to get contracts from magazine distributors for the distribution of it. And it all took time."

Howard's incentive for changing course and seeking the use of Bell material like Mr. Monster and Nelvana for the American market is also alluded to here. The shipment of issue two to Great Britain had resulted in the British Board of Trade rescinding his permit for shipping to that country. The reasons for this are unspecified here, but it caused Howard to rethink both his content and his distribution strategy. After securing the use of the Bell characters, he made a commitment with Irving S. Manheimer's Publishers Distributing Corporation to distribute Super Duper Comics bimonthly in the U.S. for three years. While leading a series with a horror-themed superhero and a female superhero was not such a terrible idea for the U.S. comic book market of 1947, the newsstands were getting increasingly crowded, and the market was evolving quickly. As the decision notes, "The venture was a financial failure, and, as a consequence, plaintiff's exhibit 1 was the last edition ever published."

Notably, Howard also published two issues of former Bell Features / Dizzy Don Enterprises title Dizzy Don beginning around the same time as Super Duper Comics #3, with no known problems getting it into the U.S., despite a similarly confusing numbering sequence and publishing gaps. That title is not referenced in this court document. The two issues of this series that Howard shipped to the U.S. were also distributed by Publishers Distributing Corporation. As for any plans Howard had to use Super Duper Comics to gain a foothold in the U.S. market, initial #3 sales numbers aside, it would have been more difficult to proceed without clarity on what he would have to do to get Super Duper Comics into the periodical category for upcoming issues. Now that the title was on U.S. Customs' radar, it likely would have taken some consistency in the release schedule. As a publisher with a history of short title runs and sporadic releases, Howard likely found that prospect problematic.

The challenge over the Super Duper Comics #3 matter did not move quickly. The court ruling itself was made on October 15, 1953 — over six years after the comic book had been shipped to the United States. Howard had presumably paid the 7.5% tariff shortly after the initial customs designation in an attempt to get the print run into the U.S. and salvage the situation, and had mounted his legal challenge in an attempt to clarify his standing for future issues and recoup his tariff costs for this issue. If we presume that U.S. Customs officials assessed the ad valorem value of the print run based on the marked cover price, then this would have cost Howard a little under $2500.00. Of course, by the time the ruling was handed down, the matter was of little relevance to all parties involved. The court eventually upheld the customs official's determination at the port of entry that Super Duper Comics #3 was not a periodical. It failed the "issued regularly at stated periods" requirement, and the reasons why didn't matter.

Bell Features ceased operations in 1953, while F.E. Howard seems to have exited the publishing business by 1949 or 1950. We'll have more on Cy Bell and Bell Features, Frank E. Howard's unusual operations, and Nelvana, among other topics, shortly.