Posted in: Comics | Tagged: Comics, jimmy palmiotti

Meet The Mayor: The Life And Times Of Jimmy Palmiotti.

By Nikolai Fomich

Two weeks ago, writer and photographer Buddy Scalera played host to a panel at New York Comic Con celebrating the life and career of comics giant Jimmy Palmiotti, in a session modeled off Inside the Actor's Studio. Scalera introduced Palmiotti as "the Mayor of Comic Books, the guy who always pays it forward, who you come to when you need help." Scalera began by playing a DVD showcasing Palmiotti's career, a mix of music and pictures taken at industry bashes. "But unlike Anthony Weiner," Palmiotti said, "I have nothing to worry about." As part of his mayoral duties, Palmiotti was on hand to help Scalera promote his new "Girls Like Comics Too" T-shirt, whole-heatedly endorsing the message.

PICTURES AND PRIESTS: YOUNG JIMMY

"I was born in 1961" Palmiotti began, "and grew up in an Italian, Irish, Jewish, and Black neighborhood, mostly Italian and Irish on my block." Palmiotti recalled his early love for toys, comics, and cartoons, and remembered watching a Bugs Bunny episode around the age of eight where the famous toon mentioned he was from Brooklyn. "I asked my dad where [in Brooklyn] he lived and he made up some baloney."

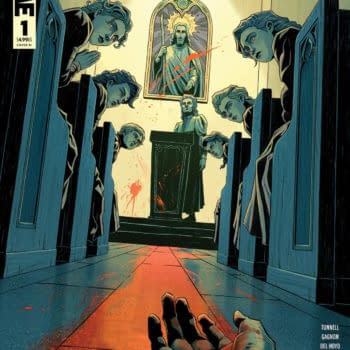

Like many Italian-Americans from his generation, Palmiotti went to Catholic school, a place every bit the rod-ruled stereotype people imagine Catholic schools to be. "I have very good posture, because they would punch or hit you they if you leaned." He said he didn't keep track of all the rules, of when and when not to eat fish, stating that he "kept the faith part, but lost all the details." Palmiotti also remained convinced that if he was going to Hell, he'd get a better deal if he lived his life with style. "[I figured] if you did it with style, then maybe you would get air-conditioning."

Interactions between the teachers and students at Palmiotti's Catholic school were dubious to say the least. "There was one teacher who would hang the kids out the window by the ankles over the street, over the fourth floor. Then there was Duffy, he was the cool priest, always outside smoking with the eighth grade girls. He had a red Trans-Am, and back then, if you had a Trans-Am… [laughs]. One day he was just gone."

Scalera asked Palmiotti about his earliest art experience, leading Jimmy to recount one of his first forays into, shall we say, funny animal cartoons.

"I would make my flip [book] cartoons in class. I won't say her name, but there was this teacher. She was not the nicest, so I drew what I thought was a great picture of a horse having sex with her. I was really into the detail – the horse tail swishing, filling in the black of the nun's outfit."

"Jimmy was already inking it," joked Scalera.

"I knew my horse anatomy. So she walked over and grabbed the picture out of my hands, held it up and said to the class, "Look, one day Mr. Palmiotti will be a very famous artist, but now he should pay attention." But she said this without looking at it! The whole class was red. [She put it down] and I took the picture and crumpled it up."

Palmiotti first attended Midwood High School, preferring a public school over a private one, as private schools "just had white kids and public schools had everybody." Palmiotti found that his Catholic school education had advanced him far beyond the average ninth grader's schooling. "I was ahead on all my studies, and so instead of taking Spanish, I drew a street in Paris for the school play. It took me the whole semester."

The young artist's talent was recognized by the school administration, and one day he came in and was immediately called to the principal's office. The principal told Palmiotti he was "wasting time in this school" and gave him subway fare to travel to Manhattan so that he could take the entrance test for the High School of Art and Design. "I was in 9th grade and this was New York in 1976, so I put my gold chain in my pocket, tried to look tough [and took the subway]. I couldn't see the city outside the subway window, there was graffiti everywhere."

At the High School of Art and Design, Palmiotti studied art and advertising. It was while there that Palmiotti made his first foray into the world of professional comics. One teacher, a Mr. Ferguson, had been asked to suggest students to help the iconic Kirby inker Chic Stone with some work. "It was a Frank Robbins' Invaders page. [Stone] was like human cigarette. I was to do backgrounds for five bucks. I went to Coney Island and drew the trains in the yard. Chic saw my work and said, "What the hell is this, a photo? Here's five bucks." He sent me home. It was too photorealistic before that became popular."

Palmiotti also ghost inked a Howard the Duck magazine for the extraordinary Gene Colan and other artists. But when he saw how some comic book creators lived, cramped in tiny New York apartments, with retractable wall beds that doubled as art boards, he decided he didn't want to get into the business.

After graduating high school, Palmiotti attended the New York Technical College in Brooklyn, where he trained as an advertising illustrator. He had applied to a free art school in New York, but, as he later learned, his acceptance letter had been lost in the mail. Upon graduation, he quickly found a job at a photo retouching studio. "I did work on Maybelline, Pepsi, movie posters for Bill Gold. I got about 100 bucks a week and years later, owned a piece of the company." It was a decent living, but Palmiotti's passion for comics remained strong underneath, waiting to resurface with a bang.

BREAKING IN: JIMMY MEETS JOE

After eight years in advertising, Palmiotti began looking for work in the comic book biz, deciding that the time had come for him to return to his love. "In 1987 I started doing background inking on Men in Black and New Humans on the side." He soon took Marvel like a quiet storm, hitting every office to look for work. Though he had left the advertising world behind, Palmiotti brought with him the type of professional conduct you learn in a 'real job' to comics. "Persistence, professionalism, knowing when to leave the room, [and] getting things in on deadline" were the keys to his success – great advice for any individual looking to break into any field.

Palmiotti soon teamed up with Mark Texeira to help out on books such as Ghost Rider and Punisher War Zone and became the "go to guy for anything behind schedule, any problem book." He would work long hours at the Marvel offices, sometimes all night. "Because I worked in real job before, I knew how to make this one work for me," he explained. As an inker Palmiotti worked on both iconic comics, like X-Force #1, where he inked the guns, and…well, Nightcat, a book Jimmy recommends you never look up. Though he continued to look for work as a penciler, it was through inking that he established his comic book career.

Through his persistence, Palmiotti built connections that would later serve to launch him into comic stardom. The pivotal encounter of Palmiotti's early career occurred when he met up with a young artist at San Diego Comic Con named Joe Quesada.

"How did you guys get together?" Scalera asked.

"We were two New York City guys in San Diego at comic con. I was standing in line waiting for some horrible hamburgers with Rodney Ramos. He introduced me to Joe, who said he could give me some cover work." The two young artists began working together on covers for Grimjack and Wizard magazine and on Valiant's Ninjak and X-O Manowar series, which became a big success for both of them. "The royalty on [X-O] was insane!"

Feeling emboldened by their early achievements, Palmiotti and Quesada decided to do what many confident young artists in the '90s did: start their own company. "Joe was feeling out what he wanted to do, I was following, and we started blowing up. We decided we should start up a self-publishing company. We were too stupid to know we shouldn't – it was less planning and more bravado. We leapt into things."

But it was that very bravado, which Palmiotti attributes to his Brooklyn "I can do anything" attitude, that led to the formation of Event Comics in 1994 and the creation of Ask, Painkiller Jane, and the team 22 Brides, a rock band that doubled as assassins. These titles served as a space for experimentation and learning for both creators, and it was at Event that Palmiotti first cut his teeth writing comics. Both young creators had found success in the industry, but they were soon to learn that such success had not gone unnoticed outside the realm of comics.

LA-LA LAND: JIMMY AND JOE GO TO HOLLYWOOD

The success of Palmiotti and Quesada's comic book work brought them to the attention of Hollywood, in the days "when options were not common." Hollywood money was an exotic idea to the two young upstarts, both of whom had come from "middle-lower income families." Palmiotti explained that while growing up his "house was connected to another house, we never had new car. We did have army jeep my dad stole in World War II, but he never let it out of the garage."

A call from a nascent studio presented the pair with a life-changing opportunity. "Dreamworks called up. [Producer] Andy Lazar said, "We want to make Ash into a movie. We'll fly you out to LA." We got a first class ticket and stayed at the Chateau Marmont in LA. We went to a screening of Wachowski's Bound. Jennifer Tilly sat right next to me – the movie was fantastic, a little odd [and I'm sitting next to her]. We were invited to a cigar bar by Joe Pantoliano…and later Jon Lovitz walks in." It was, Palmiotti recalled, a surreal experience for the two independent comic book creators.

Yet despite the glamor, Palmiotti and Quesada decided to decline Dreamworks' offer. "Walter Parks made a very lucrative offer for Ash…and out of arrogance or insanity, we said "We'll think about it.""

Palmiotti explained their thinking: "What if Dreamworks made an Ash ride, and each ride cost five bucks, and the ride lasted 30 years, and it was the hottest ride, making billions. It was money with no backend. It was a million dollar deal, but we thought, "Well we can make a million dollars making comics. We called up our lawyer, and said, "Tell them we're not interested but thank you." Our lawyer thought we were insane. Everyone thought we were insane."

Six months later, Dreamworks called again to negotiate and flew them back to LA – though this time, they stayed at the Los Monteros, which though nice "was no Chateau Marmont." The studio was in the process of getting The Prince of Egypt off the ground and was looking for more properties to franchise. Palmiotti spoke with Michael G. Ploog, who was working as a story artist on The Prince of Egypt, and asked advice from the fellow Marvelite. Palmiotti also had a run-in with Sean Pean and spotted Tim Burton, almost began believing that they had been set up to feel enamored.

This time Palmiotti and Quesada met with Jeffrey Katzenberg, described by Palmiotti as wonderful, driven, and incredibly smart. Katzenberg explained that Dreamworks envisioned Ash as a trilogy with Akira creator Katsuhiro Otomo directing. But Palmiotti and Quesada declined once more. "They gave us a back end, although it was less money than before. The producer takes half. [But] it was a good learning experience."

MARVEL NIGHTS: THE DAREDEVIL DUO

1990's Marvel was an alarming rollercoaster ride, a turbulent time when the publisher faced the loss of superstar artists to Image, the shattering of the speculator market, and bankruptcy. But while these tremors seemed to spell doom for some, Palmiotti and Quesada were as confident as ever. They used their newfound money to throw a huge industry party with an open bar, telling their friends "to drink on us for the night." Though costing them a couple of grand, Palmiotti explained that they "had the attitude that comic community was a big family. We were spending money as fast as we were making it."

That community mentality was reflected by Palmiotti's relationship to Wizard, which he said he "loved" because he got to learn the faces behind the names of fellow creators. Palmiotti's success was parallel to the magazine, said Scalera, and Palmiotti concurred, stating that "there was no better exposure than Wizard magazine if you're in comics."

Palmiotti and Quesada also began throwing parties called Marvel Nights, from which Scalera explained the Marvel Knights line had its origins. The two, said Palmiotti, in effect became "ringleaders in what became a scene." Scalera said that it was a time of major change in the industry, when lots of the older guys going out and lots of younger people coming in, including more women. "This was back when Dan DiDio had a full head of hair!" Palmiotti laughed. "Dan was a neighbor."

Palmiotti and Quesada were given the Marvel Knights imprint and used it as a platform to introduce the kinds of invigorating changes they felt Marvel needed, including new kinds of advertising. "[We thought] "Lets' do ads with our faces." We did morning shows in New York." Though Palmiotti is reluctant to take much credit, he does admit they "shook the boat" and "gave the company needed energy." As part of the deal, Quesada and Palmiotti were given the Marvel penthouse facing the Empire State Building, a place they transformed into a comfortable working space they could get to 24 hours a day.

The two also began the trend of bringing Hollywood into comics by getting "a buddy in Jersey, a movie guy" to do Daredevil. Palmiotti joked that they figured Kevin Smith owed them for Mallrats and Chasing Amy. It was perhaps the first time a major Hollywood creator had come into comics. "We didn't realize the gate we were opening up. We thought these characters were great, why aren't they everywhere?" Through Smith, the two began meeting actors like Wesley Snipes, Ben Affleck, and Matt Damon at parties. "Mingling with them you realized they're all closet comic book fans. All of these people loved these Marvel characters."

Jimmy Palmiotti had achieved the critical and financial success he had craved from an early age, his early fears of scrapping together a living as a comic book artist having long been replaced by stability and celebrity, a celebrity eventually earning him the nickname "the Mayor of Comics." But Palmiotti foresaw the drastic changes that inking as a profession was to undergo as comics entered the Digital Age. He had always wanted to be something more and decided that it was time to make the switch to writing.

Part II of this report will appear next week.