Posted in: Comics | Tagged:

'Has The Human Centipede Taught Us Nothing?' Alan Moore Answers Questions About Cinema Purgatorio For Bleeding Cool

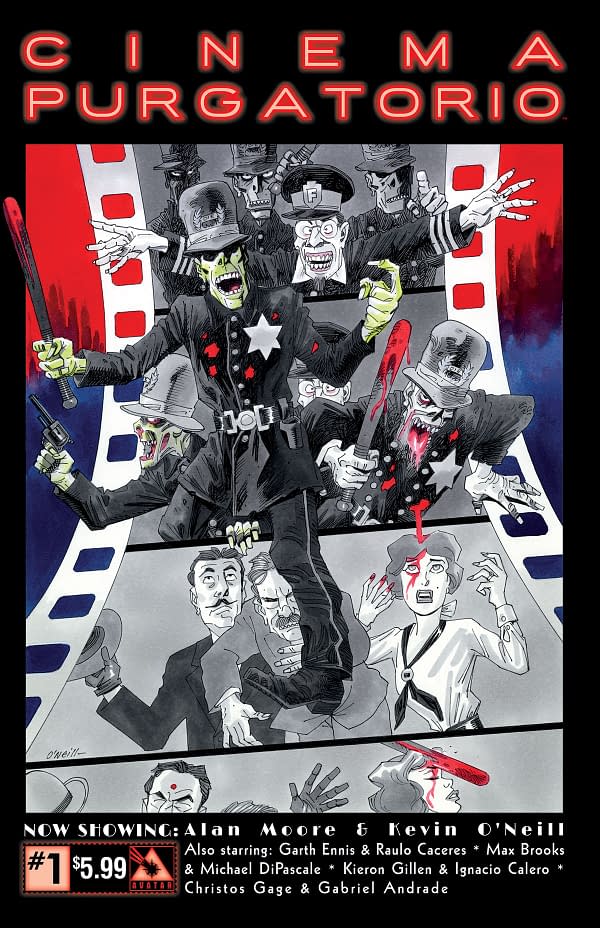

Bleeding Cool is owned by Avatar Press. Avatar are publishing Cinema Purgatorio, a new black-and-white anthology by Alan Moore, Kevin O'Neill, Garth Ennis, Kieron Gillen, Max Brooks, Christos Gage and more, funded by Kickstarter.

Which means Bleeding Cool got to put some questions to Alan….

Bleeding Cool: With Cinema Purgatorio, why an anthology? And why B&W? This seems to be the most difficult path, why take it?

Alan Moore: Well, I'm aware that a large majority of the current comic book audience are pathologically averse to anthologies, and you can certainly see their point. After all, when has anything memorable in the comic book medium ever emerged from an anthology? Except, obviously, Action Comics. Oh, and Detective Comics. And Sensation Comics and All Star and Adventure Comics. And Will Eisner's work. And Jack Cole's. And Mad and the entire E.C. line. And Amazing Adult Fantasy. And Tales of Suspense. And Strange Tales. And Journey into Mystery. And Creepy, and Eerie. And Zap. And the rest of the Undergrounds. And Comics Arcade. And 2000AD. And Warrior. And Viz. And almost all English and European comics. And almost all American comics, even single-character titles, until the 1960s. But other than that, what has the comic book anthology, or the Roman Empire for that matter, ever done for us?

My own reasons for wanting a memorable anthology title to exist, and particularly a black and white one, are twofold: firstly, I, personally, really like anthologies. Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, I think that anthologies and especially black and white ones are probably vital if we wish to retain – or, God forbid, improve upon – the basic values and standards upon which this entire art-form, let alone this entire industry, are founded. The anthology title is of tremendous value, simply because it will contain a number of strips that vary in length from a half-page to perhaps six or eight pages. The importance of this necessary limitation, to fledgling comic writers and to the writing standards of the field as a whole, cannot be overestimated. For one thing, anthology titles were once the near-universal proving ground for new writers entering the industry, based on the sound commercial logic that if you give somebody a trial shot at writing a four page story and the results are less than riveting then it will be no great disaster and no great loss. And of course someone who has learned their craft through the vehicle of the short story (where you have to establish the characters, world, premise and structure before resolving all of these satisfyingly in a handful of pages) will certainly possess all of the skills and discipline necessary to scale up their narrative into a tautly-written 24-page book, or an ongoing series, or a 'graphic novel' as the occasion demands. The same is not true the other way about, however, and writers who have entered the field via a monthly book with a potentially endless continuing story seem to find the short form unimaginably difficult and restrictive. For a lot of comic book writers it seems like the idea of resolving a storyline ever is an anathema, let alone resolving it within eight pages or less. Simply put, while mastering the short anthology story is certainly harder work for the creator, the rewards to the individual concerned and to the field as a whole are immeasurable.

The same is true for black and white comic book art, and its beneficial effects upon the quality of the field's artists and illustrators. While the massive improvement in comic-book colouring, printing, and production techniques over the last thirty or forty years has led to some exemplary pieces of work it has also given artists a lot of places to hide their flaws, in the same way that rambling continuities have provided a lot of cover for the shortcomings of writers. In America particularly, with its tradition of dividing up the pencilling and inking chores, this has seemingly led to a deficiency of artists with the abilities of, say, an Al Williamson, or a Wally Wood, or a Jack Kirby. These were all artists who were fluent in the use of blacks or in their deployment of shading techniques, all the hatching and feathering that exemplified the work of that classic generation of American craftsmen. What I'm concerned about is that abilities are being lost here, and if the comic medium is to genuinely progress and to be adequate to the coming century then I can't help but think of that as a bad thing.

Now, will the establishment of a single black and white anthology, however good, solve all of the above? No, of course it won't. What I'm hoping is that with the staggering range of talent we have lined up for Cinema Purgatorio we can establish that there were once different ways of creating and enjoying comics, and that the possibilities of this medium are far broader and more various than the current relatively narrow focus of the industry would suggest. You're probably right in stating that this is the most difficult path, but as I see things it is by taking the easiest path – as outlined above – that comic books and culture in general have ended up in their current state of creatively-threadbare stasis. Ideally, I'd like our little creepy backstreet bug-hutch to become the venue for a newer, more progressive and more rigorous approach to the possibilities of the comic book. With popcorn.

BC: Comic stores can much more easily sell another Star Wars or Batman title. Why should they risk anything on Cinema Purgatorio? Hasn't the war for "new" been lost?

AM: If the 'war for the new' has indeed been lost then there is now, officially, no point to the continued existence of our culture or, conceivably, of our species. If the massive asteroid were to hit us now, it wouldn't be any great loss. Luckily, I don't think that the situation is anywhere near as bad as that. I mean, what you're describing wasn't really a war, was it? It was more the mass capitulation of a generation or so of creators – or 'content providers', to use the current terminology – to the fact that, for the most part, they and their culture no longer possessed the capacity to generate new ideas or to bring those ideas to competent fruition. That's not a war. Having been born in the aftermath of quite a serious war, I can assure you that there'd be a lot more bombsites, ration books and fondly mentioned relatives you never got to meet. No, a closer analogy to what's happened to culture is more like if we neglected or worked everybody who actually understood, say, farming to death, replaced them with people who had enjoyed farm produce at one point in their lives and who had thought "Well, how hard could that be?", and had subsequently seen our entire bio-diverse cultural landscape turn into a barren wilderness that yielded only one increasingly nourishment-free variety of potato. A lot of this might well be related to the ease of modern production methods engendering a certain laziness throughout culture, as mentioned above, but it still isn't a war if we do not have an enemy except our own complacency and inertia.

And while comic book stores, in the short term, would be much wiser to invest in the latest movie-related spinoff, they might have cause to question how the long term effects of this policy have seen the greater part of the comic industry transformed from a genuine source of fresh ideas and energetic culture into a shrivelling appendage of Hollywood. They might also reflect on a lot of the out-of-nowhere successes of the last few decades, which would have all been occasions where the most sensible thing to do would have been to keep ordering the same steady-sellers and ignore the risks inherent in a new idea or title, even though today's new ideas very frequently turn out to be tomorrow's blindingly obvious classics. This was certainly record producer Joe Meek's philosophy back in the early sixties: when he had a proven number-one hit on his hands with the Tornadoes, why should he risk anything by managing a bunch of unknowns like the Beatles?

Seriously, if the struggle for the new is over, then I wish someone would tell the forces of history, which seem to be propelling our world towards an anxious and uncertain future at an ever-accelerating pace. I'm sure that some of you might have noticed that this isn't the same planet as it was last year, or even last week. The truth of our situation is that we are being washed away by a tsunami of the new, and by the very nature of its unprecedented novelty we don't have a clue how to handle it. Thus we stand, gaping, pretending it isn't happening, engrossed in the exploits of a character we remember from when we were twelve, humming a tune that was popular in the mid to late Seventies. Traditionally, this is what art and culture are meant to instruct us in, and if they have a purpose it is to help us assimilate and deal with our changing worlds, both external and internal. When we were going through the convulsions of the cataclysmic change from agriculture to industry back around the juncture of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Mary Shelley was able to articulate those new fears and aspirations by inventing the science fiction genre in her wildly avant-garde novel Frankenstein. It is the responsibility of genuine artists to create work which is sufficient to their turbulent times, and in my opinion you cannot accomplish this by continually rebooting and recycling the pop culture of the Sixties, Seventies and Eighties. How is any new culture – music, films, comics or literature – that is adequate to our modern situation going to emerge if there are all these shiny, re-imagined nostalgia-fetishist franchises standing in the way? Are we doomed to endlessly recycle the pre-digested waste products of the culture preceding ours, passing it on to the culture following us until the end of time? Has The Human Centipede taught us nothing?

The war for the new will never be over until one moment ceases to be followed by the next, and to declare that it is over simply because some creators on the front line have decided that they don't have the stomach for it anymore, or because they can no longer remember how to load or use the weapons at their disposal, is to ensure that our culture is numbered amongst that war's casualties, or perhaps fatalities. I have heard it said that there are those among the contemporary audience who feel it is their right to have the characters that they enjoyed as children grow up alongside them (which I think generally translates to "I am not yet ready to give up masturbating while thinking about Catwoman"), but I contend that this can only lead to a menopausal Strawberry Shortcake, Captain Marvel in incontinence pants, and Richie Rich in a nightmarish toupee declaring that Muslims, Mexicans and any other darkly-complexioned peoples beginning with 'M' should be prevented from entering America. I think we should ask ourselves if that's the kind of world we actually want.

BC: What is it about the old theatres, and old films in general, that screamed out to you? Why do they need to be covered in short stories?

AM: I think my original idea was "black and white horror anthology", with the "black-and-white" and "anthology" elements of that premise already explained. When it came to the "horror" part of the equation, I think both Kevin and I realised that it would require a little more thought. One of the things about comic book anthology horror is that with very few exceptions it seems to have relentlessly followed the (admittedly excellent) E.C. template of twist-ending stories that are made palatable by framing them within the comforting gruesome puns of a "horror host". Since Kevin and I were looking for a workable seam of modern experimental horror, something that broke out of the existing model, this didn't seem the way to go. We understood that all the Crypt Keepers, Old Witches, Uncle Creepies and Cousin Eeries served an important function by linking all of the unconnected stories in the anthology with a single wryly cynical commentator, but we felt that there was probably a more novel way of providing that linking element than simply using another knocked-off Charles Addams amusing ghoul. Meanwhile, thinking about the kind of stories we wanted to tell and the way we wanted to tell them, we went through a kind of useful false start by considering all of the inventive and demented American horror comics of the 1950s that weren't E.C. There was something in the frequent experimentalism and the anything-goes mania of those stories that we found exciting, but at the same time it didn't seem to lead anywhere other than some sort of affectionate tribute to that neglected stratum of comic book culture, which may have been fun but didn't seem particularly useful. After thinking over what I personally found creepy and atmospheric, and after talking with Kevin about our very similar childhoods in the working class England of the 1950s and 1960s, the memory of the peeling and dilapidated side-street cinemas of that period seemed to stand out in particularly sharp focus. The grandiose and exotic names – Rialto, Essoldo, Tivoli, Ritz – that concealed the worn-out and vaguely haunted interiors; the grey-tone lobby cards promoting some forthcoming second-string horror flick or nudie feature, always uncomfortable if you were nine and escorting your mother to see Alan Ladd in Shane for the fifth time; the dream-like atmospherics of those shabby yet palatial environments and the air of mysterious, gloomy adult concern that hung around the staff and the patrons in a stale cigarette fug…every element from the content-free Film Review magazines available from the bitter-looking woman in the ticket booth to the slightly gangster-like aura of the otherwise avuncular manager seemed to drip with unsettling memories and associations, and I think we both instinctively felt that this was potentially rich ground in which to commence our excavations. It also came to us that in lieu of a comedy necrophile horror host to give the disparate stories in the anthology some sort of continuity, actually having a disturbing backstreet picture palace as our central linking conceit was quite a good alternative. After a little more consideration, the name Cinema Purgatorio seemed to emerge full blown as a kind of seedy and threatening venue that's at the other end of town from Cinema Paradiso.

Surprisingly, once we'd hit upon that central concept of a creepy and liminal cinema that was for some reason showing these unnerving little B-movies, our ideas for the stories we wanted to tell and the storytelling devices we wanted to use seemed to come thick and fast. I think my own main contribution was mentioning an ingeniously-themed anthology of short stories that I'd read by the magnificent Robert Coover – I think it may have been called Plus Full Supporting Features, or I may have got that completely wrong – which in the prologue established a drunk and despairing manager of a condemned regional cinema, alone in the projection booth on the night before his venue is demolished and maniacally running several films through the projector at once, so that the celluloid scenarios literally melt into each other. The rest of the book is a cinema programme with a cartoon, a documentary short, a main feature, a continuing serial and so on, each one a strange and affecting little vignette that gets its effect from mutating our expectations of these familiar tropes and genres. That seemed to offer a promising way to go, as did a few other bits and pieces that came to mind, such as a short story in a Peter Haining anthology about a long-lost print of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari that had different scenes each time it was watched, and a surprising number of dreams or nightmares that I'd experienced in childhood that seemed to take place in one of these plush and disintegrating establishments. By far the bulk of the input on the strip, however, has come from Kevin, which is probably not surprising given the massive influx of ideas and inspirations which he contributed to the League. Kevin is a repository of information and enthusiasm regarding some of the more obscure and little-known backwaters of the motion picture industry, and has dished up a multitude of proposals where it has then been my task to express the essential horror or disturbance that is inherent to them. It was also Kevin who hit upon the idea of what is essentially a flexible eight-panel grid, since this would preserve the screen aspect of a traditional movie in the familiar dimensions of the panels. And it was Kevin, when we were two or three episodes into the project, who most perfectly encapsulated what we were struggling our way towards by saying that it wasn't really horror movies we were concerned with so much as the horror of movies: our work in Cinema Purgatorio seems to be focussing in on the uneasy aspects of the way we watch films, with our simultaneous awareness of the lives of the actors and directors and production companies that are going on behind the painted flats, and our conditioned acceptance of cinematic conventions that are in as complete a contradiction of reality as anything that H.P. Lovecraft ever attempted, simply because we've grown used to them and barely notice them anymore. This, to us, seems to have opened up a new and unexpected vein of horror stories which are different in their effect to anything that we or the audience have ever seen before. I suppose that if you were looking for a single tenuous precedent in the field of comic storytelling you'd have to go back to an occasional feature in the early days of Mad magazine, and say that Cinema Purgatorio is "Scenes we definitely wouldn't like to see".

Obviously, one strip does not an anthology make, but I think that the rest of the fare lined up for Cinema Purgatorio promises a potential classic. The truly memorable anthologies of the past had a few things in common, after all, including powerful and focussed writing (as with Gaines, Feldstein and especially Kurtzman at E.C., or the immaculate Archie Goodwin, the finest comic writer to ever grace the American mainstream, on Creepy and Eerie), and a range of artists with unique styles and old-school illustrative talent. I think that with me, Garth Ennis, Max Brooks, Kieron Gillen and Christos Gage we have some serious writing muscle behind this book, and with Kevin and Raulo and the other highly distinctive and individual artists involved we are never going to be putting out an issue that is anything less than visually fascinating and innovative. In certain respects, I think our anthology promises the same things promised by the sinister, flickering fleapits that were our inspiration: strange and possibly shocking features that you are never going to see in any of the more brightly-lit and hygienically-maintained multiplexes of the comic medium, and a lingering atmosphere that clings to you long after you've stumbled out blinking into the daylight.

BC: This is the first major project you and Kevin have undertaken since League, how does it feel to be switching gears with such a long-term creative partner?

AM: I suppose the short answer would be "necessary". The realisation that we'd been working on The League for fifteen years just kind of crept up on us – for all of the huge amount of work that the series entailed it didn't seem like a decade and a half – but once that fact had occurred to me, I saw straight away that it must have been a different experience for Kevin than it had been for me. During that time, simply by virtue of the difference between how writers and artists work, I had been able to work on a whole slew of other projects including Jerusalem, Dodgem Logic, the Showpieces film project, the Unearthing album, film, book and performances, and the other comic book projects that I handled in that period. By contrast, and even though The League is a strip that allows a tremendous amount of variety, Kevin had been working solely on that for fifteen years, and it must have occurred to him that if he'd actually murdered somebody he'd be out by now. While we have a final volume of The League planned for a year or so's time, and while we were both really enjoying the different scenarios, eras and locations of the Nemo trilogy, we felt it was necessary to take a break and do something radically different, in order to return to the finale of The League with all of the freshness and new ideas which that climax deserves and demands. And Cinema Purgatorio, whatever else it is, is about as far from The League thematically and stylistically as it is possible to get. Without the brilliant Ben Dimagmaliw's spectacular colouring, Kevin is working in the extraordinary range of black and white styles and techniques that made his 2000AD work such a joy, and with the basic "different movie every month" premise of our section of Cinema Purgatorio we can explore a whole new spectrum of story possibilities, without the necessity for them to be meticulously worked into a pre-existing tapestry of continuity that already contains pretty much the entirety of fiction within it.

As to how it actually feels to be making such a radical move after our lengthy stint on The League, I'd say that it obviously felt daunting and exciting in equal measure, the way that these things generally tend to do. When we were just launching into the strip and the idea was still in its formative stages, I think both of us were slightly worried that we might have come up with a concept that simply didn't have enough implicit ideas or fresh material to go the distance. By the time that we were starting the second eight page instalment, however, we'd both had the realisation that in story terms we'd inadvertently stumbled upon a diamond mine. Just making a small shift in the way that we were approaching the medium of film (via the medium of comics) seemed to open up an entirely new way of looking at things, with a resultant dazzling array of new narrative possibilities. By episodes three and four – "The Flame of Remorse Returns" and "A King at Twilight" if you're interested, fear-fans – we were both becoming quietly convinced that these were about the best stand-alone pieces that we had ever done in our respective careers. Considering how fleeting and ephemeral some of our source material is, I think we've both been a bit startled by some of the profoundly human statements that have emerged, as if from nowhere. Also, given that our brief and our intentions are to create horror stories, we've both been pleased to discover a new breadth in that remit. Each issue we're able to work with a genre that we may never have worked in before, and we find that we're playing all of the notes on the horror piano rather than bashing out the same dark, heavy chords down at one end of the keyboard. In the grimmest of pieces there is always at least an incongruous humour, while it's in the most ostensibly light-hearted pieces – like our romantic comedy, "The Time of Our Lives" – that the most dreadful and gut-wrenching impacts are concealed. We're finding that horror has a lot of different flavours, and in Cinema Purgatorio we're hoping to extend and educate both our own and the readers' palates. And you never know, the reader might discover that they're looking at forgettable old films completely differently and becoming aware of some of the uncomfortable shadows in the background. That has certainly been our own experience thus far, and there are an awful lot of movies or movie devices that I personally am never going to see in the same light again.

BC: You have some massive projects coming out and off your mind with Jerusalem and Providence. Does that fuel your excitement for something new, and radically different, like Cinema Purgatorio?

AM: I'm not sure that's how it's working with me these days. For one thing, although the first draft of Jerusalem was finished the October before last, I still have quite a lot of work to do on the book before it's completely finished, and even then I'm not expecting it to be ever entirely off my mind. In my experience you can have finished writing a book decades ago and still find that it is taking up an inordinate amount of time in your ongoing present day life. Even with Providence, where I'm still finishing the last of Robert's commonplace-book entries, I think I'll probably be answering questions regarding the work for some considerable time to come, if only those of hardcore Lovecraft scholars, or conceivably occultists uncertain of the provenance of Hali's unusually authentic Booke. Each of these projects – and the other ongoing projects that I'm still involved with – is like a steep hill or a mountain, depending on their scale, and while I'm still apparently capable of mounting several big, slow mountaineering expeditions at once, I'd be lying if I said that I accomplished things these days as easily as I pulled off the perhaps less ambitious projects of twenty or thirty years ago: these days, I find juggling a number of projects to be far more exhausting, and if anything explains my undoubted enthusiasm and excitement regarding Cinema Purgatorio, it is purely to do with the inherent qualities of the strip itself, and with all the startling new possibilities that the work is suggesting to us, rather than because of any burst of energy on my part. I also think that one of the big attractions for me and Kevin is the largely non-continuing basis of the strip. Yes, there is an overarching story being told obliquely and slowly in the first/second-person narrative captions of our mostly-unseen cinema-going protagonist, but the meat of each episode is clearly the individual pieces of film that this character is watching, and it's there that the two of us are having the most fun. We can leap from one mood or approach or genre to another in little six page jumps, and in the nine or ten that we've completed so far we've been able to make surprisingly concise and pointed observations about the Western, the Roman epic, model animation, the animated cartoon, the adventure serial, the screwball romantic comedy, the silent film, the murder mystery, the Marx Brothers-type comedy… pretty much everything, in fact, except for the horror movie. This allows both of us to indulge a different artistic or storytelling whim with every issue, and while it also involves the additional work of coming up with a different world, characters and style every six pages, the benefits in terms of freshness and variety will, I think, be glaringly evident. Also, the fact that we're avoiding the horror genre seems to be forcing us to unearth entirely new disturbing narratives from all of these unlikely other sources, and that sense of new ground being broken and a sudden surge of innovation is very heady and exhilarating. Certainly for me, and I suspect for Kevin, that rush of discovery in itself is what is providing the burst of impetus and energy for Cinema Purgatorio, and in my case that energy is despite the fact that I'm a wheezing wreck of a man crawling towards the finish line of several consecutive marathons, rather than because of it.

Cinema Purgatorio is currently the highest funded comic book Kickstarter underway right now, with 800% of its goal achieved.