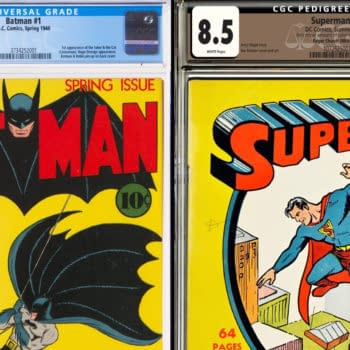

Posted in: Comics, Vintage Paper | Tagged: blue book, pulps, Red Book, spicy history stories

Pulp Publisher Louis Eckstein, "The Munsey of the Western Field"

Magazine and Pulp pioneer Louis Eckstein launched important titles Red Book and Blue Book and had an expansive career beyond the newsstand.

Article Summary

- Louis Eckstein, a Chicago publishing pioneer, launched influential titles Red Book and Blue Book.

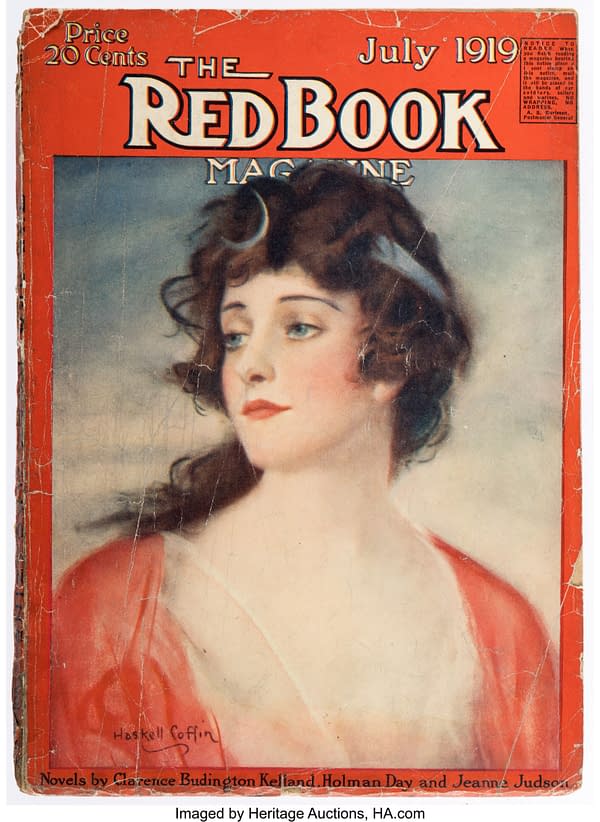

- Red Book used market research and unique photo features for its early success in the pulp market.

- Eckstein's diverse ventures included railroads, real estate, and the Ravinia Festival.

- His legacy spans pulp publishing and operatic endeavors, influencing cultural and literary scenes.

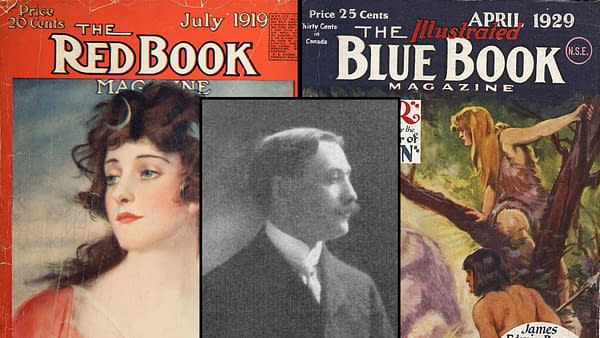

Blue Book is considered a foundational early pulp title with contributors that eventually included the likes of Edgar Rice Burroughs, Zane Grey, Robert A. Heinlein, Agatha Christie, and countless others. Still regarded as an important pulp series by collectors and historians today, the Blue Book title was launched in 1905 by its publisher in the wake of the earlier success of Red Book. As we discussed in our previous installment about the Daily Story Publishing Company, Red Book itself had been launched specifically due to the success of that publisher's 10 Story Book. All of these developments took place in Chicago in the late 1890s and early 1900s, involving a number of business and newspaper figures of that city. By 1910, the success of Red Book had its publisher Louis Eckstein being hailed as "the Munsey of the western field" (by which they mean he was based west of New York City) by industry trade magazine Printer's Ink., a reference to foundational pulp publisher Frank Munsey, who had already achieved great success in this era.

And with that, welcome back and it's time for Spicy History Stories #7, the seventh installment of a regular column about pulp magazine history that we've launched to coincide with Heritage Auction's weekly pulp magazine auctions. Unlike other auction-centric posts we've done here, this column is not necessarily designed to be closely tied to any particular items up for auction. Mostly, it's this: if you enjoy the nerdy details of comic book history, you're going to love the astounding (and yes, sometimes weird) history of the people and companies that made the pulps.

To recap what we learned last time, the sequence of events leading to Red Book and beyond started with the Chicago retail, restaurant, real estate, and mail order partnership of Stumer, Rosenthal & Eckstein, which provided financial backing for the Daily Story Publishing Company. Daily Story was initially a syndicator of short stories for newspapers, but then launched the fiction periodical 10 Story Book. Stumer, Rosenthal & Eckstein parted ways with Daily Story and its founder Dwight Allyn, and decided to use what they learned from the early months of 10 Story Book to launch their own fiction magazine. On the advice of Chicago Daily News managing editor Charles M. Faye, they hired one of Faye's newspaper correspondents Trumbull White to be the editor for this new magazine, which would be called Red Book. The new magazine's offices were in the Stumer, Rosenthal & Eckstein partnership-owned building at 158-165 State Street in Chicago.

Rail Lines, Real Estate, and a Magnate of the Musical World

According to Herbert Fleming's 1906 overview of the Chicago publishing scene, Stumer, Rosenthal & Eckstein partner Louis Eckstein was tapped as the head of Red Book's original publishing entity Red Book Publishing Corporation, as it was felt he had the most first-hand knowledge of the periodical publishing business among the partners due to his prior position of general passenger agent of the Wisconsin Central Railway, where he dealt regularly with advertising in an enormous array of newsstand periodicals. Eckstein had also dabbled in publishing to promote travel on the Wisconsin Central lines, and in 1885 launched a monthly periodical called Wanderer, which has been described as a Wisconsin Central in-house publication for its employees (and possibly customers), supported by advertising from its business partners.

Louis Eckstein (1865-1935) was born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, the son of clothing merchant Samuel Eckstein and his wife Anna. According to one source, in his early days he aspired to be a concert violinist, but decided he did not have the gift for it. Eckstein's first job was as a messenger boy for the Wisconsin Central, and he worked his way up from there at that railroad over the next several years. Eckstein, Louis M. Stumer, Abraham R. Stumer, and Benjamin J. Rosenthal formed a partnership in 1891, launching The Emporium in Chicago that year and quickly expanding into other businesses.

As with the rest of the partners, Eckstein was involved in a dizzying array of business interests, in his case prominently related to a major cattle car company, real estate, and restaurants, among his other endeavors. During his lifetime, he was best known for his substantial involvement in what is now known as the Ravinia Festival. In 1911, Eckstein and others acted to save the 36-acre Ravinia site from the bankruptcy of its previous owners, as Eckstein guided it into including opera performances. Ravinia began in 1904 as a sort of tourist attraction, including a music pavilion, theater, casino, and athletic field initially created by the Chicago & Milwaukee Electric Railroad. About his involvement in Ravinia and particularly its now-famous musical component, one 1925 profile that also noted his tendency to avoid publicity would say, "One of the most enterprising and least known of the magnates of the musical world is Louis Eckstein, director of the Ravinia Opera Company. Few operatic directors exert so independent or complete a sway over their organizations; few impresarios are so much responsible personally for the success of their seasons, and few operatic chiefs are so absolutely removed from public scrutiny as Mr. Eckstein. The Ravinia Opera is the project of an individual who stands responsible for it because of his own delight in maintaining an opera company."

Putting the Red in Red Book

When Red Book debuted in 1903, literary magazines with colors in their names had been a trend over the prior decade. This started most famously with London's Yellow Book, followed quickly by the equally influential Black Cat in America, and soon came to include the likes of Gray Goose and Frank Tousey's White Elephant. According to an editorial in its debut issue, the color red was chosen here to reflect the nature of the magazine's contents. "Red is the color of cheerfulness, of brightness, of gayety. It is the most brilliant color in the spectrum, and the one which is chosen — so scientists tell us — as the most beautiful, by four out of five persons. It is the color of the most brilliant displays in nature, from sunsets to autumn foliage. Therefore, The Red Book."

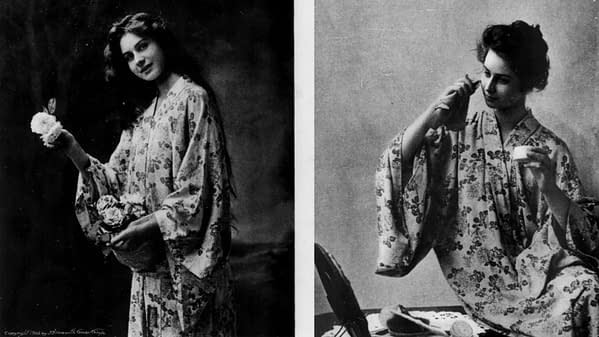

There is some confusion among pulp histories as to the original nature of Red Book, due to its much later incarnation as a women's magazine. But Red Book launched as a general audience fiction-focused magazine that also prominently included "photographic art studies" of beautiful women. This photo feature was key to the magazine's early success. While the photos are not nearly as scandalous as contemporary descriptions of this regular photo feature made them sound, they did raise eyebrows, with George Bernard Shaw reportedly asking if there were any Chicago magazines that featured photos of beautiful men, when the magazine asked if he would write 12 articles for Red Book's first year. Shaw declined the offer.

Eckstein likely got the idea for this photo feature from Western News Co.'s Elias A. Shepler. According to Fleming's account: "First the publishers prepared a small preliminary edition, of which only twenty copies were completed and taken to the Red Book office. They were never circulated. This preliminary number contained only a meager collection of stories and no photographic illustrations. A sample copy was taken to Mr. Shepler, the Western News Co. manager, experienced in seeing Chicago publications die on the news-stands. Mr. Shepler told the publishers that, as it then appeared, their book was no better than any of the many ten-cent story magazines, and therefore it would not go. They stopped the binders. They enlarged the magazine, and added an illustration feature. The illustrations of the stories in the experimental number, as in the first six regular issues, were zinc etchings which looked cheap. For this reason some half-tone feature was especially desired. In the enlarged initial number a series of pictures in a 'photogaphic art' department filling the first pages of the book was inserted."

Beyond this sort of shrewd market research, Eckstein showed the same resourcefulness in marketing and soliciting feedback. Per Printer's Ink in 1910: "Each month advertisers and agents all over the United States receive a special Red Book box, containing a copy of the magazine itself and a handsome photogravure of an actress. In the beginning this monthly box went out with a copy of the Red Book and a miniature set of ten-pins, used to emphasize some advertising moral. Next month some other trinket was sent to make a point, and the following month something else, until, by a process of learning the demand, it was discovered that everybody liked handsome pictures of popular actresses, and these were adopted as a staple souvenir. Mounted, ready for hanging, they are not only given places in offices and homes, but convey something of the Red Book's character."

Cheap Paper and the Theater

Eckstein and his partners were willing to absorb significant costs to make Red Book a success. Printer's Ink would later quote a figure of $1 million in expenses, including printers' bills and top rates paid out to contributors before the tide turned and the title became profitable. But the tide did turn, and Red Book's success quickly spawned imitators, most notably Street & Smith's Smith's Magazine. Eckstein soon followed up on his own success with Blue Book in 1905, which was launched under the initial title Monthly Story Magazine using unused and/or unsuitable story contributions from Red Book. And unlike Red Book, Blue Book used "the cheapest kind of paper" but featured a higher page count. Green Book (initially Green Book Album) followed in 1909, featuring photos and coverage of theater actors and novelizations of plays.

While not achieving quite the historical reputation that Blue Book would, Red Book would come to include fiction from Edgar Rice Burroughs, Booth Tarkington, and F. Scott Fitzgerald, among others. In 1929, magazine publisher McCalls Co. acquired control of Consolidated Magazine Corp (the corporate shell that owned Red Book and Blue Book at this time). As reported by Time Magazine, Eckstein received 25,603 shares of McCall stock valued at over $2 million in the deal. Louis Eckstein died on November 22, 1935 at his apartment in the Drake Hotel in Chicago. He had continued to pursue his passion for music late in life, becoming a director of New York's Metropolitan Opera Company in addition to his stewardship of Ravinia.