Posted in: Comics, Recent Updates | Tagged: batwoman, brian k vaughn, brian wood, Comics in the Classroom, education, fiona staples, greg rucka, jh williams iii, john bultena, Lazarus, matt hawkins, saga, The Massive, think tank

Bringing JH Williams To Class Sparks Using Creator-Owned Comics In Education – The Bleeding Cool Interview With John Bultena

When I reported on JH Williams III's panel at San Diego Comic Con this past summer, replete with mind-bending artwork from his numerous projects from Batwoman to preview art of The Sandman: Overture, I noticed what a stellar job the moderator and interviewer, John Bultena of the University of California, Merced, was doing. I was delighted when we struck up a correspondence by Twitter and e-mail about his experiences using comics in education at the university level, since I'm also an educator.

Bultena pushed the envelope by bringing in JH Williams' Batwoman as a central text for teaching, and followed that up with a surprising move. Since he knew Williams personally, he asked the comics creator to pay a classroom visit. The results were pretty extraordinary. Considering the success of what he had accomplished for students with Batwoman, Bultena is now setting out to do something even more challenging: bringing a wide swath of creator-owned comics into education. It's a course of action that's going to bring with it some headaches for him, since very few educators are making such a bold move. But it's also a plan that could reap massive rewards for students and pave the way for diversity when using comics in curriculum. Here's a recap of Bultena's experiences and plans in his own words:

Hannah Means-Shannon: What's your background academically and in comics? How did you arrive in a position to bring comics into an academic setting?

John Bultena: I hold two Masters Degrees, one in Philosophy and Literature obtained at CSU Stanislaus, where I did my undergraduate work in Philosophy. The other is a Masters of Library and Information Sciences from UCLA. Undergraduate work was largely on continental Philosophy, dealing with questions of language, art, and literature; spending a lot of time on Gadamer, Nietzsche, Bataille, Derrida, among others. My initial graduate studies, I focused on Philosophical concerns of literature, which culminated in a thesis on H.P. Lovecraft discussing the relationship of fear and wonder. After instructing developmental English at Merced Community College for four years, I went into the Library and Information Sciences program at UCLA. There I did work on information seeking behaviors in file sharing communities along with critiques of digital comic books regarding human computer interaction.

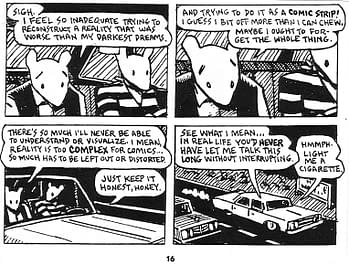

What really set me off on wanting to use comics and graphic novels in class was an incident at UCLA. So there I was, at a great institution, having a Masters Degree stemming from deep readings and writings on Philosophy and fours years of English instructional experience. In a class were doing cataloging, writing descriptions and entries for books. No problem, old hat for me. I am then presented with a lithograph to catalog and I realized I was never asked to really write about an image in any of my English or Philosophy classes, nor had I ever had students do something similar. I had done Philosophy of art, but that involved a lot of engagement with texts. It was a shock and something I wanted to remedy for other students involved in an increasingly visual learning environment.

HMS: What kind of comics are usually used in courses that incorporate graphic narratives? What kind of courses tend to be open to using comics in the classroom?

HMS: What are the pros and cons of using well-known graphic novels?

JB: Pro – support. This entails support on a multitude of levels. The established canon of graphic novels (Maus, Watchmen, Persepolis, etc.) are on lists of books for some departments. If not there, then there are varying bibliometrics that can be looked up to see if one of these is appropriate for a course. This means that a department has justification regarding their curriculum standards for a text. Also academic popularity means that other established faculty may be more approving.

Further support comes from the amount these texts have been used. That can mean looking at a syllabus from another course at another school, lesson plan availability, pedagogical studies of the respective texts' use, and plenty more. I could approach at least two other instructors at Merced College about what sort of exercises they did using Persepolis without an issue. It should also be mentioned that publishers and even Diamond Comics Distributors, Inc. provide newsletters about relevant graphic novels and some even have lesson plans provided.

Further support comes from the amount these texts have been used. That can mean looking at a syllabus from another course at another school, lesson plan availability, pedagogical studies of the respective texts' use, and plenty more. I could approach at least two other instructors at Merced College about what sort of exercises they did using Persepolis without an issue. It should also be mentioned that publishers and even Diamond Comics Distributors, Inc. provide newsletters about relevant graphic novels and some even have lesson plans provided.

Finally, book ordering. Book ordering can be a hassle. If I want to use Persepolis at Merced College, no problem, the school's bookstore has them from other classes, used in many cases. This means students will have easier access and many options for access (whether used sales or textbook renting).

Con – The titles mentioned as canon are all good, but because they have such huge penetration in academics there is an ever increasing chance that a student has engaged that text before. Often this means that a student may not be engaging the text for the current class to the degree they should be.

Another con is part of using any popular text: academic dishonesty. The more popular a text and longer it has been around the more likely a student will be to pull something off the Internet. I recall using Shirley Jackson's "The Lottery" for a class and having nearly one-third of the papers come back with some sort of plagiarism.

I really try to keep my classes fresh. This makes sure the material is new and dynamic, the students love the idea of being trailblazers. But it also means I am keeping on my toes about what is going on in the class. It is easy to get locked into using texts repeatedly and assigning the same stuff as a college instructor.

HMS: What do you think the benefits would be of using indie or creator-owned comics in the classroom?

Because of the stagnation in the major houses (DC specifically) I will be primarily using indie/creator-owned books for my classes in the foreseeable future.

HMS: Have you approached indie creators about this? What is their reaction or what do you think it would be?

JB: Not directly. I did tweet that I was going to be using The Massive next semester for my critical thinking class and mentioned Brian Wood in the tweet. I said he "writes an ethically complex world that is all too possible" and I got a favorite from him. But I think the creator's side of things would aide students in understanding the significance of these issues.

HMS: If you want to bring indie comics into a course, do you think there would be distribution problems? Would it be an issue getting course books for students?

JB: Not really. I have never had an issue with the bookstores on campus getting copies. Also with the abundance of means to obtain both physical and electronic copies of books there is little issue with it. Having a background in library sciences, I always investigate the capacity to obtain enough copies of a text for my classes. However, one of the bookstore at one of the institutions I work at only allows instructors to introduce so many new texts to their classes ever so many years. So if I pick something, it needs to be relevant for a while and even useful across multiple classes.

HMS: Tell us a little bit about working with Batwoman in the classroom. What was student response like?

All these are enlightening for students. Finally, having access to Williams was a big thing regarding the use of this text. Interview is an often overlooked research resource. Before the semester began, I asked Williams whether he would be willing to take a few student questions via e-mail. He said this was not a problem. Well, as when I started telling him how the class was going and inquiries the students had, he offered to come to the class and be interviewed. I believe he viewed this as a new challenge professionally. That one class session turned out to be one of the highlights of my career in higher education

One reaction of a student's stands out especially. While reading the part of Hydrology when La Llorona attacks the children in the church, one student who was usually quite vocal was silent. When I asked him what he thought of the section, he said that he was awe struck by just how the church depicted looked exactly like the one he attended with his grandmother in Mexico. There was a deep connection made there. Relevancy can be very difficult to establish with students and Batwoman just hit it home with nearly all the students, whether the use of La Llorona, LGBT culture concerns, or just enjoying a good crime fighting story.

HMS: What did it add to your course to have JH Williams visit? Did that change student perspectives on comics?

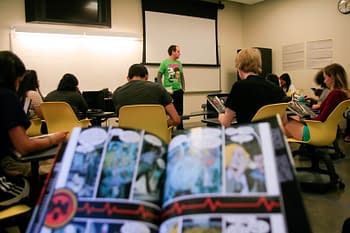

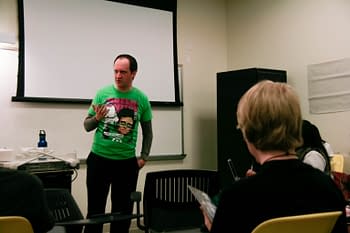

Alongside this, it added to the student experience. That was a class session they would not forget. I did not let the students know that Williams was coming to the class that day. What I had told them was to come up with two to three questions to pose to Williams, then I would select 10 to submit to him via e-mail. Instead, Williams came to the class, portfolio of Batwoman original art in hand, and answered questions for the students for almost two hours. The questions ranged from how he did his research on La Llorona to his methodology as a writer. A professional writer taking time with a class of 20 freshman really gave the students confidence in what they are doing and definitely showed them the significance writing can have in someone's life.

HMS: Do you think creators themselves benefit from visiting a classroom and getting involved in education?

JB: Williams has expressed to me that the encounter was excellent and "fascinating." He is use to fielding questions from fans, but the types of questions students doing research were different. Sure, a few of the students asked some fan-type questions ("who's your favorite comic book artist?") but the vast majority of the questions were about his methods of researching topics and how he co-created such a fantastic multi-cultural narrative in Batwoman. This really gave him some insight into how his stories come off outside the world of comic book fans. Some students were doing research about women in law-enforcement (a theme in Batwoman) and asked Williams about why he depicted so many women in law-enforcement when in reality women make up a very small percentage of law-enforcement.

[John Bultena and J.H. Williams III after their panel at SDCC 2013, photo by Aaron Devrick]

Another question was, "Taking in account that you are not a lesbian or of the Hispanic culture, what responsibilities did you feel you had as a writer when writing Batwoman in regards to how they were portrayed?" These are critical questions that hopefully will help Williams in his future narratives. He was able to field all the questions and had more than satisfactory answers for all of them, but they definitely gave him a pause of self-reflection and consideration both that, I hope, strengthen his future work. Seeing what a different type of readership that really poured over and had varying agendas got out of his work certainly left an impression on Williams.

So yes, I do believe creators can benefit from a classroom or campus visit. Even as a writing instructor, professional writers blow my mind, especially all the plotting, planning, coordinating, and understanding of visual arts that go into it. And when a writer has like four or five titles they are doing concurrently, mind boggling! A level of writing discipline goes into that and I hope to enable that sort of discipline in my students, but for the comic creator encountering a class I hope they can see some of those fundamental aspects of their craft they may have come to overlook. At the sametime it is good to see what sort of messages a critical audience is getting out of it, especially one that is going to be formulating genuine academic arguments about their points of view on a respective story.

HMS: What's your game plan so far? How do you hope to tackle this issue in upcoming courses?

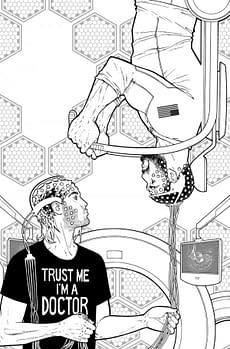

JB: My current plan is move more towards using creator owned comics in classes over stuff from the big two. As aforementioned, I am instructing a critical thinking/writing course at Merced College next year and will be using three comic book related texts, The Massive Vol. 1, Saga Vol. 1, and Understanding Comics, alongside traditional critical thinking textbook. The plan is to look at traditional argument and fallacies, but then lead into Understanding Comics to examine visual argumentation (something often overlooked in coursework for lower division students and more relevant than ever in our culture). With that background, the students will then transverse two major topics throughout the semester: environmental policy impacts on geopolitics and corporate censorship.

But that is all only for my classes. I think this ability to connect students to issues, culture, and other things via comics if fascinating. The students have fun, I have fun, but at the same time we are developing dialogues among ourselves and with the texts. But when a creator, like Williams, can step into that dialogue and answer questions for us it helps us create new questions, concerns, and paths of critical exploration. To move these opportunities into the future, into bigger and broader horizons, I would like to put the call out to comic creators to engage with faculty at universities and colleges about the use of their work in classes. I think a partnership of the like could produce some really great conversations about pedagogy, writing, professional writing, and just be an all around fun experience.

Anyone interested in these topics or who just want more information should feel free to contact me.

E-mail: bultena.john@gmail.com

Twitter: @OnlyPlayWizards

*[All other photos provided courtesy of Mark Paragas]

Hannah Means-Shannon is Senior New York Correspondent at Bleeding Cool, writes and blogs about comics for TRIP CITY and Sequart.org, and is currently working on books about Neil Gaiman and Alan Moore for Sequart. She is @hannahmenzies on Twitter and hannahmenziesblog on WordPress. Find her bio here.