Posted in: Comics, Recent Updates | Tagged: Comics, entertainment, gary frank, geoff johns, liam sharp, peter david, sam kieth, The Incredible Hulk

Social Activism In Peter David's The Incredible Hulk

By Bart Bishop

Peter David has always injected his politics into his work. As early as his third issue into his 12-year long run on The Incredible Hulk, #333, he explored domestic violence and gun control. In 1994 and 1995, however, within nine months of each other he tackled AIDS and abortion in overt manners obviously meant to provoke reactions. In the long view of comic book and pop culture history they've slipped under the radar in terms of recognition, but 20 years later looking back at "Lest Darkness Come" and "A Little Death" reveals that while neither issue is particularly subtle, they are brave and progressive at a time when few other mediums engaged with the same subject matter. Those that did often came across as cloying or pedantic. David clearly bled all over his typewriter, because he's angry here and yet evenhanded. It's appropriate that a character that stands in for hounded or repressed minorities is the one to take a stand for those grinded down by hate and ignorance. What's more refreshing is that David isn't afraid to instill his own personality and voice in the Hulk, creating a well-rounded and consistent character whose lack of a "clear win" in both issues makes for a melancholy yet eye-opening read.

#420 comes in at the tail end of the Hulk's tenure with the Pantheon, the team inspired by Greco-Roman myth. In it Hulk saves Jim Wilson, a former sidekick introduced in 1970, during a protest rally in which Jim has been hit with a brick. In the hospital Jim begs Hulk for a blood transfusion to save his life (he'd been living with AIDS, as revealed in #388, December 1991), much like Bruce Banner had done for his cousin Jennifer Walters that transformed her into She-Hulk, but Hulk refuses on the grounds Jim may become a monster. While Jim succumbs to his disease, Betty Banner is working at a call center attempting to talk down a man that has called her confessing to thoughts of suicide after learning he is HIV-positive.

There's eloquence and heart on display in this issue, even if the intersection between Hulk and Betty's storylines is a bit heavy handed. The cover, entirely black except for a spotlight over Hulk at Jim's bedside, is accompanied by a red ribbon showing solidarity of people living with HIV and AIDS. Every aspect of the story is heightened by Gary Frank's gorgeous artwork. His clean lines and expressive "acting" on the part of his characters was usually utilized to great humorous effect, but here makes for truly heartbreaking sequences of human frailty. It's clear why Frank has gone on to do high-profile work with the likes of Geoff Johns over on Superman.

Jim was a well-rounded character with a unique voice and a full if not nearly-forgotten history with the title character. He had already been reintroduced during David's run and established as HIV-positive, possibly kept on the back burner for just such an occasion, so this feels like the culmination of a plot thread rather than a cheap gimmick. Betty's story, by contrast, feels reactionary. The man she talks to, Chet, is a white man, a football player driving a Ferrari, that is scared to tell his friends because they'll think he's gay. This is didactic storytelling, as if David was prematurely reacting to any criticisms of stereotyping African-American men with AIDS with Jim, but the insistence on having two straight characters with AIDS feels like a cop-out, screaming, "It's not just gay men!" Luckily a balance is found during a brief scene with Hector and Ulysses, brothers and members of the Pantheon together, as Hector laments the association between AIDS and gay men. An already openly-homosexual character, this reads like an authentic gripe rather than the dramatized mouthpiece of David.

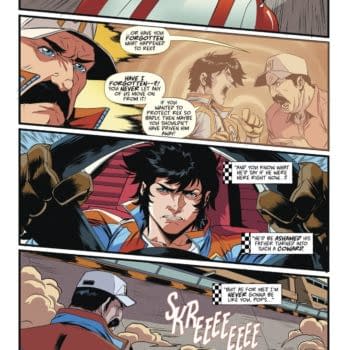

While #420 is designed and presented explicitly as dealing with an important issue, #429 is a little more coy. The cover claims that it is "A Tale That Will Make You Angry", but the issue at hand, abortion, is never laid out. Hulk and Betty, who have been living incognito after things with the Pantheon didn't work out, discover a young pregnant girl rooting through the trash. Betty takes Kate (who is never given a last name) to the local clinic where it turns out a riotous demonstration is taking place. When Hulk learns of this he races to intervene, but not before the clinic has been lit on fire and Kate gets shot (ironically in the stomach) during the chaos.

There's a similar minimalist component to the cover, with an all-black background and an enraged Hulk cradling a hurt Betty in the foreground. The aforementioned text accompanying this image is desperate to get attention, but in a misleading way that pulls punches. David may have achieved success with his previous socially conscious issue, with #420 even including letters from the comics community who have dealt with AIDS, but #429 is rushed and more concerned with furthering the ongoing, serialized narrative rather than confronting taboo subject matter. It doesn't help that artist Liam Sharp is widely inconsistent compared to Frank. His Hulk is a grotesque exaggeration, with swollen biceps in direct opposition to the incognito lifestyle he and Betty are living. Reminiscent of the baroque, dream-like quality of the likes of Sam Kieth, Sharp makes for dynamic images under different circumstances that just aren't appropriate for this grounded, grim tale.

The story itself suffers from a weightless take on heavy matters. Hulk and Betty stumble into meeting Kate, with the latter taking it upon herself to look out for this girl she barely knows and Kate herself reduced to a plot point. She immediately trusts Betty, with any character development happening off-screen, and dies without having made a decision about her own body. She's not karmically punished for wanting to have an abortion: she's a random victim of violence and mob mentality. If she had been introduced earlier her death would be tragic, but as is it's barely felt. It's also insensitive to attempt a thematic connection with Betty and Hulk sleeping together (in Banner form but with the mind of the savage Hulk…confusing times), perhaps for the first time in years, with what? The physical act of love as some sort of counterpoint to the previous brutal act?

Not many comics creators attempt to deal with such important, delicate issues but David has always been a bravado champion of the little guy. The only other creator that springs to mind is Judd Winick, who kicked off his career with the beautiful Pedro and Me about his friend that died of AIDS, and subsequently interwove stories of the perils of cigarettes (Morph discussing his mother's lung cancer in Exiles), hate crimes (a homophobic attack on a friend of Kyle Rayner's in Green Lantern) and HIV (Mia as Speedy, the most prominent superhero dealing with the disease, in Green Arrow). Unfortunately Winick's attempts at education reeked of shock value, with Winick himself getting national attention and appearing on CNN. David, who received little to no attention for his earlier thrusts at cajoling change, was much more successful at communicating his intent without coming across as preachy.

Although issue #420 is certainly more successful in terms of drama and ground breaking, #429 can't be completely dismissed. It has the best of intentions, but feels like it's holding back. Still, 20 years later it's eye opening to realize that this kind of quiet bravery and compassion in mainstream superhero comic books is a rare thing indeed.

Editor and teacher by day, comic book enthusiast by night, Bart has a background in journalism and is not afraid to use it. His first loves were movies and comic books, and although he grew up a Marvel Zombie he's been known to read another company or two. Married and with a kid on the way, he sure hopes this whole writing thing makes him independently wealthy someday. Bart can be reached at bishop@mcwoodpub.com.