Posted in: Comics, Vintage Paper | Tagged: pulps, spicy history stories

Shudder Pulp Decade: The Emotional Effect Produced by Extreme Fear

Weird Menace: The 1930s rise of the Shudder Pulps followed by the rise of the forces that ended them and transformed horror on the newsstand.

The article Horror on the Newsstands by Bruce Henry in the April 1938 issue of the American Mercury appears to be the first known usage of the term shudder pulp, at least by inference. Henry begins the article by staking out the territory he's going to be talking about here, at a time when horror pulps were booming, and their critics were coming for their cold, dead hearts: "This month, as every month, some 1,580,000 copies of terror magazines, known to the trade as 'the shudder group,' will be sold throughout the nation. Between their frankly lascivious front covers and their advertisements for masculine pep tablets in the rear, these titillating contributions to American belles lettres will contain enough illustrated sex perversion to give Krafft-Ebing the unholy jitters. Never, in fact, since the popularity of the Marquis de Sade, has civilization seen such a plethora of Frankensteinian literature as is now circulating in this land of peace and goodwill."

With that rather lurid opening paragraph from the heart of the Shudder Pulp era, it can only be time for Spicy History Stories #5, the fifth installment of a weekly column about pulp magazine history that we've launched to coincide with Heritage Auction's weekly pulp magazine auctions. Unlike other auction-centric posts we've done here, this column is not necessarily designed to be closely tied to any particular items up for auction. Mostly, it's this: if you enjoy the nerdy details of comic book history, you're going to love the astounding (and yes, sometimes weird) history of the people and companies that made the pulps.

That 1938 American Mercury piece, bolstered by a mention in Reader's Digest that year as well, is an often-referenced touchstone in articles and books about the Shudder Pulp era, but for the wrong reasons. In recent decades, it has been held up as an attack on pulps, and it almost certainly is not that. American Mercury was known for its scathing satire, of which Horror on the Newsstands is an obvious example. As Frank Luther Mott notes, "readers must have been impressed with the prominence of satire in the magazine, a satire that often ran into iconoclasm and 'debunking,' as the term went in those days."

In the prior decade, American Mercury had itself been the target of the kind of attack that Shudder Pulps were subsequently facing in the 1930s. In 1926, American Mercury co-founder H.L. Mencken stood up against would-be moral gatekeepers by selling a copy of an issue of his magazine containing a profile of a prostitute directly to his primary critic, thus triggering his own arrest for distributing immoral literature. Mencken and American Mercury's eventual victory in that case left its mark. Months later, the magazine chose to pulp the print run of an issue featuring an article titled Sex and the College Girl rather than risk further problems. And in 1927-1928 when U.S. Congressmen such as Thomas W. Wilson began proposing legislation for a National Board of Magazine Censorship, American Mercury was prominent among the magazines drawing his outrage, alongside the likes of Film Fun, Pep, and Burten's Follies.

That 1926 American Mercury matter (called the Hatrack case) had not been Mencken's first brush with the attempted suppression of magazines and pulps, and he played an undeniable role in the early development of what became the spicy pulp market. Also the co-founder of iconic crime pulp Black Mask, Mencken had chosen a successor to be the editor of American Mercury before 1938, but it's difficult not to wonder if Bruce Henry is a pseudonym for Henry Louis Mencken. Mencken obviously had a deep familiarity with pulps and was known to employ dozens of pseudonyms throughout his career, while Bruce Henry has no other bylines in American Mercury. This aside, it has also been noted that "The Mercury was not only political; it was fierce, especially in its attacks on Puritanism."

Horror on the Newsstands

Horror on the Newsstands in American Mercury appears to be lampooning the frequent overreaches and tactics of such moral watchdogs, and likely of one watchdog in particular who was at that time leading a large organized campaign against pulps and magazines which he believed had "diabolical intent" to destroy the fabric of American society. To make his satiric point, writer Bruce Henry outlandishly compares the effects of horror pulps to the Marquis de Sade, the Grand Inquisitor of the Spanish Inquisition, and the horrific torture and other wartime atrocities of the (then ongoing) Spanish Civil War, as he works up his mock outrage over pulps. He then carefully avoids leveling specific criticisms against any real pulps by instead spending the next seven pages (!) of the American Mercury making up a hypothetical Shudder Pulp, which he calls Squirm Stories, and explaining the contents of each story it contains in lurid detail. The stories described were said to be written by a hypothetical author, "Fructon Mahanowell, a hollow-chested fellow from up Boston way who used to write basement store ad copy and answer to the name of Bill Johnson. He has a wife, two fine children, and a passion for burnt almonds, but he can whip out the most blood-curdling fiction on the market."

The piece ends on a more realistic note by suggesting that readers will tell you that it's the pulp writers (and presumably, the strength of their work by extension) who get them to buy such magazines and that not only does the article author agree with that, but he himself used to be involved in the pulps. This again seemingly opens the door to the possibility that Bruce Henry is really Mencken, though obviously there are other possibilities. Notably, the article author's phrase "the shudder group," and later in the piece, "shudder magazine," is a detail that cannot be found in the magazine publishing industry trade magazines of the day. Despite that, it's difficult to interpret if this too is an element of the satire, or if it really was a term commonly used by publishing insiders in that day. The more straightforward phrase "horror pulp" did occasionally make its way into the newspapers of the era. As with the rest of it, perhaps Henry thought "shudder magazine" would be a more startling and memorable turn of phrase. In that at least, he would prove to be on the nose.

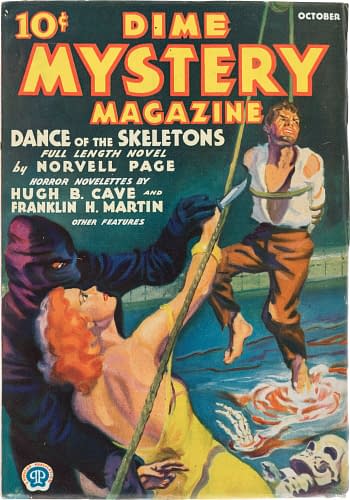

- Dime Mystery Magazine – October 1933 (Popular)

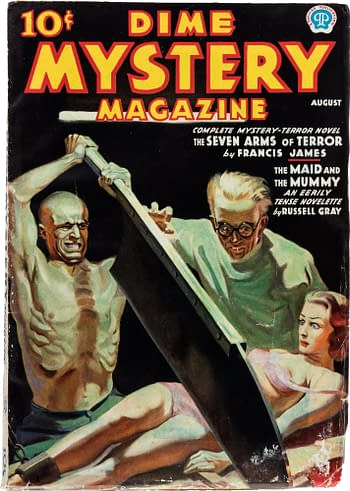

- Dime Mystery Magazine – August 1937 (Popular)

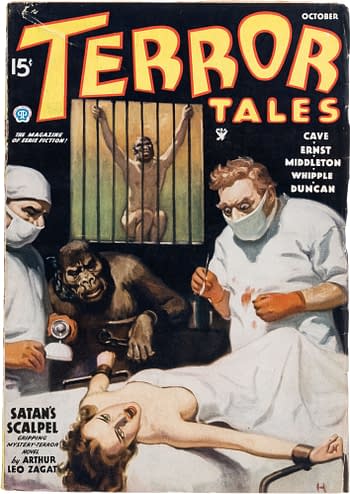

The Emotional Effect Produced by Extreme Fear

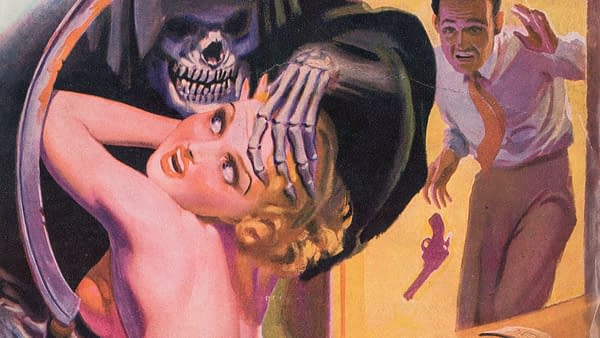

By many accounts, the Shudder Pulps began with the October 1933 issue of Dime Mystery Magazine, launching a new era of what pulp fans now also call weird menace. According to The Shudder Pulps: A History of the Weird Menace Magazines of the 1930's by Robert Kenneth Jones, an editorial in that October 1933 issue notes, "There were good mystery stories and good terror stories appearing in half a hundred different publications long before this magazine ever reached the newsstands… but no magazine, to our knowledge, had ever combined these two elements of mystery and terror and devoted its pages exclusively to stories of this one heart-quickening type."

Popular Publications publisher Harry Steeger was inspired to this shift by a trip to France, which included a visit to the Grand Guignol Theatre. A look at the theater posters [1][2] and photographs [1][2] from the 1920s-1940s era of the theater makes this influence clear. As quoted by the book Danger is My Business by Lee Server, Steeger later recalled, "They had the Grand Guignol Theatre there, with these violent situations, and the audience was very enthusiastic. I thought, we could do a magazine like that with the same sort of emphasis."

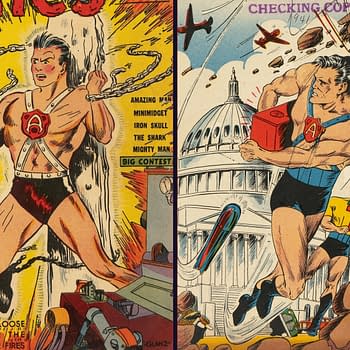

While it's obvious that Popular Publications was the early driver of this trend, calling firsts can be tricky business, and there are numerous issues of Popular pulps before October 1933 that might call that exact starting point into question. For example, the July 15, and September 1 1933 issues of Dime Detective and the August 1933 issue of Dime Mystery among many others are going to be considered Shudder Pulps by most modern collectors based on their cover elements alone. Some earlier pulps from other publishers may also come close to the necessary look and feel as well. And even if Steeger didn't enact the changes inspired by the Grand Guignol for interior stories before October 1933, based on the evolution of those covers, it's clear the shift had been on his mind for a while before that.

The target for this type of material continued to evolve. As competitors caught on and Popular Publications themselves expanded, Popular editor Rogers Terrill explained in the January 1935 issue of Writer's Digest what it was looking for in this area. "To describe accurately the emotional effect we seek in Terror Tales and Dime Mystery, it is first necessary to make clear the difference between horror and terror. Horror is the emotion we feel when we see something hideous, gruesome, sordid; something that we find extremely disgusting or revolting. Terror is the emotional effect produced by extreme fear; it is horror brought home to us personally, the knowledge of something horrible about to happen to us or to someone dear to us, and which menace we are almost powerless to combat."

In that same 1935 commentary, Terrill also made the obvious point that "We will permit a fairly heavy sex angle; in fact, our villains are often sadistic. Risque situations are permissible provided they are handled tactfully and are a logical, necessary part of the horror-menace situation."

Rival titles like Thrilling Mystery, Spicy Mystery, Mystery Tales, and many others soon entered the field. But all periodical fiction eras must come to an end. In one early signal that the Shudder Pulp era had passed its peak, when Rogers Terrill again explained his requirements in Writer's Digest for September 1937, where it was noted that he was "cutting down on the sex element."

- Terror Tales – October 1935 (Popular)

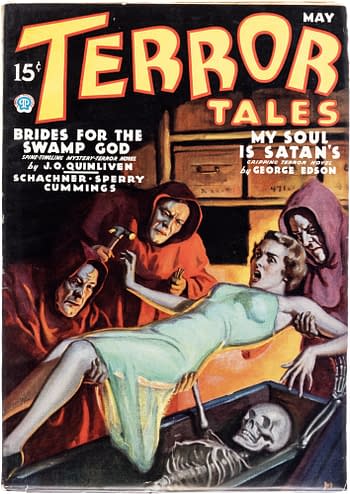

- Terror Tales – May 1936 (Popular)

An Evil of Such Magnitude

What happened? Campaigns against pulps and other magazines on claims of obscenity had long been part of the newsstand periodical landscape, and had continued to come and go throughout the 1930s. For example, in 1934, the New York City Commissioner of Licenses Paul Moss ordered 59 magazines off the newsstands there, including a number of pulps, such as Harry Donenfeld's Pep Stories, Spicy Stories, and Gay Parisienne. Similar actions in other cities on the part of local leaders and police forces around the country continued steadily throughout the decade.

By 1937, church groups were getting involved, and by the next year, they were getting organized. If the Shudder Pulps had their version of the Pre-Code comic book era's Fredric Wertham, his name was Bishop John F. Noll of Fort Wayne, Indiana, who is likely the true target of American Mercury writer Bruce Henry's satiric venom. Noll headed the National Organization for Decent Literature (NODL) to tackle what they viewed as the problem with pulps head-on. As laid out in the paper The Esquire Case: A Lost Free Speech Landmark by Samantha Barbas, Noll believed that "traffic in pulp magazines was 'an evil of such magnitude as seriously to threaten the moral, social and national life of our country.' He saw 'diabolical intent' on the part of magazine publishers 'to weaken morality and thereby destroy religion and subvert the social order.' Noll believed that it was the Catholic Church's duty 'to organize and set in motion the moral forces of the entire country' to protect Americans, especially the young, from the menace of immoral magazines."

According to Barbas, the NODL was extremely effective via its ability to enlist the support of Catholic churches and their members at scale around the country. She notes that, "According to the NODL, within its first two years it had cut the number of 'disgusting publications' in the country from 175 to 45. It allegedly forced at least thirty publications out of business and compelled others to clean up. In one city, NODL members persuaded thirty-seven drugstores and newsstands that it was better to forego sales and remove offending magazines than incur the wrath of the organization."

By 1940, local city officials ranging from San Francisco mayor Angelo Rossi to New York City mayor Fiorello Laguardia, were on board this push against so-called offensive magazines. Police actions around the country soon followed throughout that year. Officials of Kingsport, TN raided newsstands suspected of selling obscene magazines. The president of major New York area regional newsstand distributor Interborough News Co, Julius Stolz, was arrested on the charge of distributing obscene magazines. A woman in Buffalo, NY was arrested in her home and charged with possession of obscene magazines that police apparently found under her mattress. The cumulative impact of similar such actions effectively spelled the end of the Shudder Pulp era, or the beginning of the end, at least, as publishers scrambled to adjust their output to survive.

- Spicy Mystery Stories – November 1936 (Culture)

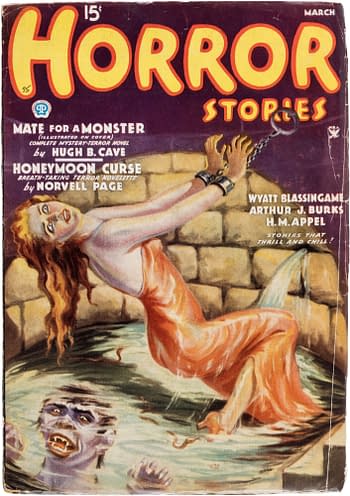

- Horror Stories – March 1935 (Popular)