Posted in: Comics, Vintage Paper | Tagged: abner sundell, alex hillman

The FBI, Comic Pros and the Fake News Controversy of the 1964 Election

This post started as a Chilling Adventures of Sabrina article, largely about MLJ/Archie comic book editor and writer Abner Sundell — with maybe a footnote or two about Sundell's weird blunder into the political realm in 1964, which I've been meaning research further ever since I stumbled across it in 2017. A couple of WTF-inducing stretches of research later, it's something else entirely: a forgotten example from American history of how pop culture and the people who make it influence politics. There are way more such examples of this magnitude than you'd think, from the realm of comics, pulps and dime novels. Virtually all of them are little-remembered by history — despite numerous instances of court and/or Congressional testimony, investigative files, and other evidence. The elections of 1880 and 1896 are two other particularly good examples, and we'll get to those and more in time.

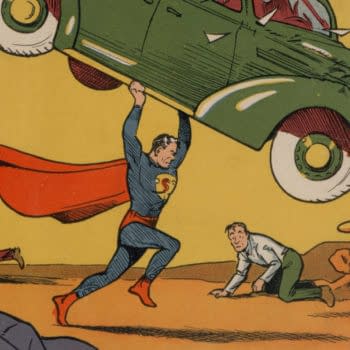

The Chilling Adventures of Sabrina character Madam Satan, played by Michelle Gomez in the recent tv series from Netflix, was created for comics in 1941 by artist Harry Lucey and writer Abner Sundell. Madam Satan first appeared in Pep Comics #16 (note: this comic book is in the public domain), cover-dated June 1941. Abner Sundell co-created other MLJ (The publisher now known as Archie) comic book characters such as Steel Sterling (with artist Charles Biro), and became the publisher's managing editor — Archie debuted under his tenure, as did many other foundational MLJ properties of that era.

Sundell had a fascinating and wide-ranging career as an editor across pulps, comic books, and magazines. He got his start writing and editing for the pulps, where he eventually crossed paths with Louis Silberkleit — the man who put the "L" in MLJ. He hired Charles Biro during his tenure at MLJ — who went on to become a notable comics editor himself at publisher Lev Gleason (Daredevil Comics, Silver Streak Comics, Crime Does Not Pay). Sundell also worked for Victor Fox, as writer and editor for Fox's comic book and magazine lines.

Madam Satan creator Abner Sundell's career as an editor eventually landed him a central role in a Congressional hearing investigating the truthfulness and purpose of some specific media activities in the United States election cycle of 1964. But before that, another little-remembered figure from comic book history made a startling leap from minor comics industry player to major league political operative, to help set the stage for that election. About the changing media climate that this era represents, it was noted during that hearing:

Mr. Chairman, when it comes right down to it, irresponsible attacks on Members of Congress are not simply attacks directed at human beings… They are attacks on our political system.

This is a new phenomenon that technology has made possible. It has been a factor in more and more campaigns. The great ease of editing [media] has opened a whole new realm of distortion to the unscrupulous political campaigner or to the unscrupulous or irresponsible individual or organization outside the realm of politics that wants to abuse or, indeed, to annihilate a responsible political figure.

—Bruce L. Felkner, Fair Campaign Practices Committee, Hearing before the Special Committee to Investigate Campaign Expenditures, December 17, 1964

J. Edgar Hoover and the Comic Book Publisher

Following a successful career as a comic book writer and editor, Abner Sundell became an editor for Pageant Magazine, during the 1960s. Pageant Magazine was launched in 1944 by comic book, magazine, and book publisher Alex Hillman. The magazine was composed of what had become a typical mainstream men's magazine formula along the lines of the earlier Esquire Magazine and similar titles — fiction, politics, and news wrapped up in covers and photo features of attractive women.

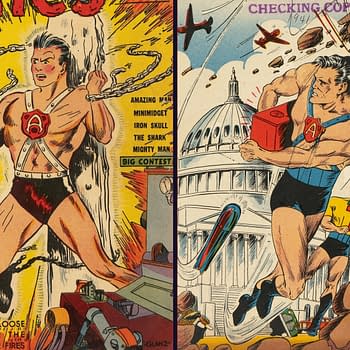

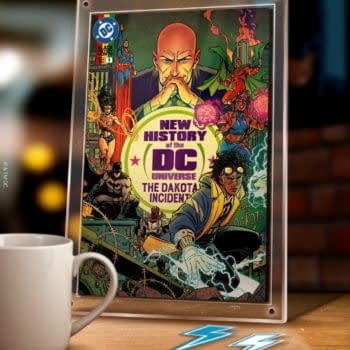

Remembered today as the publisher of comic books titles such as Air Fighters Comics, Airboy, and Rocket Comics, Hillman's life, and business operations ranged well beyond comic book publishing, and his career as a publisher and political raconteur of sorts took some odd twists and turns.

Hillman was a law student at the University of Chicago during the dawn of what became known as the Chicago School of Economics at that university, which encompassed teachings in related academic areas such as business and law. The Chicago School became known for applying economic theory to other fields such as politics. In later times, Hillman was among those who helped fund the Economics Department there via endowments after the Ford Foundation halted their funding. The Chicago School has produced some 30 Nobel Prize winners in economics, including most famously, Milton Friedman. Friedman attended Chicago a short time after Hillman, and the school's economic theories have been influential on conservative politics.

Hillman's interest in a spectrum of fields including publishing, economics, art, and politics seems very informed by his time at the University of Chicago, but employing what he learned there in the publishing business soon brought him to the attention of J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI.

In January 1939, the FBI opened an investigation into Hillman regarding "Interstate Transportation of Obscene Matter" for the Hillman magazine Crime Detective. Investigating agents quickly determined that the magazine was not obscene and that the investigation was seemingly politically motivated. It had been instigated by an Assistant U.S. District Attorney at the behest of associates of Pennsylvania Governor George Earle, whose administration ended in scandal that year. Earle and various associates in the city of Philidelphia had been the subject of the issue of Crime Detective in question. The investigation was ultimately dropped.

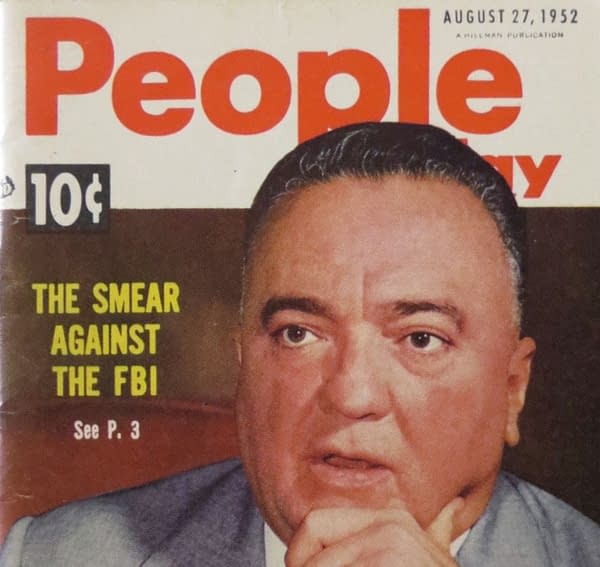

Hillman was back on Hoover's radar again in 1952, for an article regarding the FBI in his magazine People Today, which also featured Hoover himself on the cover. Of note, the memo regarding this matter refers to an unincluded 1943 memo that recommended that "the Bureau steer clear of any relations whatever with Hillman Periodicals, Inc" due to what it termed as Hillman's unsavory reputation.

The 1952 memo is a fascinating microcosm of the FBI under Hoover. Noting that "Although this article was not derogatory, it was unauthorized", the investigation subsequently found that People Today had run a number of other FBI articles that were likewise positive but unauthorized. But "since Hillman bears a bad business reputation" it was recommended that the company again be investigated for possible violations of the Interstate Transportation of Indecent Literature statute — in seeming reprisal for having the temerity to run such unauthorized articles.

The subsequent investigation (which includes the fascinating tidbit that the FBI had used a former agent now working at rival Fawcett to gather info on Hillman) again turned up nothing illegal, and the matter was dropped. However, the FBI did note with some interest that in 1950, Hillman had picked up an important (and controversial) business associate: Senator Styles Bridges became a member of the Hillman Periodicals board of directors.

Bridges was the Senate Minority Leader 1952-53, and President pro tempore of the Senate 1953-55. He was an ally and defender of Senator Joseph McCarthy during the period when McCarthyism became synonymous with witch-hunting. Bridges is perhaps best remembered today for his alleged role in threatening fellow Senator Lester Hunt with publicizing the fact that his son was gay during the then-upcoming election campaign. Hunt withdrew his bid for reelection and shot himself in his Capitol Hill office.

Apparently quite impressed with his comic book and magazine publishing associate's business acumen (not to mention his Chicago School credentials), Styles sent Alex Hillman to France in 1953 to lead an investigative team for the Senate Appropriations Committee regarding a proposed $5 billion economic aid package for that country under the Marshall Plan. Hillman's report was sharply critical of the French government and concluded that they were using American aid to avoid raising taxes.

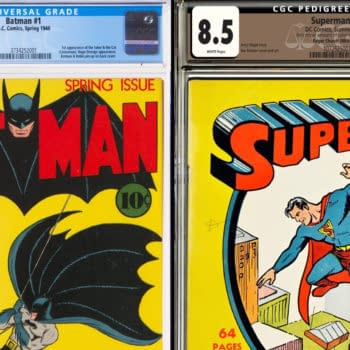

It appears that the relationship between Bridges and Hillman was beneficial to both parties. The December 29, 1952 issue of Newsweek made note of the fact that Hillman had pulled all of the comics out of the display case in the Hillman Periodicals office lobby. He was getting out of that end of the business, he'd told them, to focus more on magazines. The last Hillman Periodicals comics were cover-dated March 1953.

The timing of that exit from the comics business turned out to be a remarkable bit of foresight on Hillman's part. Because a few months later, the last Hillman comics were being pulled from newsstands during the same month that two of Hillman board member Styles Bridges' colleagues on the Senate Armed Services Committee — Estes Kefauver and Robert Henrickson — publicly floated their intention to form a committee to investigate juvenile delinquency in the United States. The subsequent hearings included a highly public grilling of comic book publishers by the Senate, which in turn ultimately led to the Comics Code.

Being spared the embarrassment of having to defend his publishing line in front of a Senate Subcommittee seems to have done wonders for Hillman's reputation — at least in the eyes of a certain other government agency. By the time Alex Hillman resurfaced in available FBI files a few years later, it seems that they'd done an about-face on their opinion of the comics and magazine publisher. In a memo seeking more info about the author of a Pageant Magazine piece covering FBI Agent Melvin Purvis, a publicity-friendly agent of the 1930s who is best remembered for being the man who took down John Dillinger, the investigating agent notes:

We have had favorable relations with Pageant Magazine, and they have printed a number of favorable articles regarding the Bureau. The Director [J. Edgar Hoover] saw Alexander Hillman of Hillman Periodicals on 5/6/60

Hillman would exit the publishing business entirely shortly after that, but it was the popularity of his publishing swan song, a paperback titled Conscience of a Conservative, which became his most noteworthy contribution to the direction of modern political history. The success of Conscience of a Conservative is said to have convinced its author, U.S. Senator and eventual Senate Intelligence Committee Chair Barry Goldwater, to run for President. The blurb on the current edition of the book says, "It influenced countless conservatives in the United States, and helped lay the foundation for the Reagan Revolution in 1980." Hillman's fellow University of Chicago alumni Milton Friedman would become one of Goldwater's policy advisors during the 1964 election campaign.

Along the way, Hillman accumulated a noteworthy circle of political associates — including conservative commentator William F. Buckley Jr, who worked with Hillman on various magazines, and who occasionally name-checked his old comic book and magazine publishing associate in books. That's all quite a foray into politics (and I've left out a bunch of it. I'll write more about Mr. Hillman another time) for the nearly-forgotten publisher of comic book characters such as Valkyrie, Airboy and The Heap. But Hillman was not the only individual from the comic book industry whose career path brought him to an important contributing role in the 1964 election.

The Comic Book Editor's Political Moment

Under Hillman, Pageant Magazine became well known for its presentation of polls and other data. The April 1949 issue polled the nation's top economists, who predicted an economic slump in the face of a potential decline in Cold War spending by the government, for example. On a lighter note, the next issue that year informed us that they had determined that there were 20,000,000 dogs living in the U.S. at that time (I couldn't resist looking up the current number — it's 89.7 million dogs as of last year, according to Statista). In its later years, the magazine advertised itself with the rather creepy tagline "The Magazine that Reads You."

But by 1961, Pageant had been acquired by another company with a deep history in the pulp and magazine publishing industry, Macfadden. The publisher had merged with Bartell Broadcasting Corporation in 1961 to become Macfadden-Bartell. As an aside, Macfadden's historical output is considered highly influential on the origins of the American comic book industry, right down to playing an incidental role in the "discovery" of Superman. Macfadden-Bartell would continue to be a major player in the newsstand periodical field for decades, acquiring well-known magazines such as Us, and even a partial share in the National Enquirer.

All of which is to say that by the time that former MLJ/Archie Comics editor Abner Sundell arrived at Pageant in the early 1960s, the magazine's political, polling and data bona fides had been established — at least among the public.

What happened next requires some context: the 1964 election is almost universally considered one of the most brutal elections in U.S. history. Its strategies and tactics echo through our elections to this day.

For Goldwater's part, his campaign marked the beginning of what became known as the Southern Strategy. His supporters called the media "the rat-fink Eastern press", and his rallies were a startling departure from the norm:

The aim of the revellers was not so much to advance a candidacy or a cause as to dramatize a mood, and the mood was a kind of joyful defiance, or defiant joy. By coming South, Barry Goldwater had made it possible for great numbers of unapologetic white supremacists to hold great carnivals of white supremacy. They were not troubled in the least over whether this would hurt the Republican Party in the rest of the country.

As for Lyndon B. Johnson, his successful candidacy was considered a certainty. Having assumed the presidency just a year prior due to the assassination of John F. Kennedy, Johnson had stepped into the role at an extremely difficult time — Vietnam, the threat of nuclear war with the Soviet Union, and civil rights issues all loomed large — but he'd done well in the eyes of most of the country, and had passed the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964 earlier that year, banning discrimination by race, religion, or sex.

But Johnson was a man who left no detail to chance. Often described as adept at manipulating the media, Johnson employed a spectrum of tactics during the campaign that ranged from hardball to frankly shady. Then Special Assistant to the President Bill Moyers captured the intent of the campaign in this August 17, 1964 memo:

This is no time for me to be tactful with you. There is too much at stake.

No one knows better than you why we took on the Presidential campaign. There is only one reason. We are ardent Democrats who are deadly afraid of Goldwater and feel that the world must be handed a Johnson landslide.

…

We agreed that a very necessary part of the campaign is that part devoted to the voting public the absurd, contradictory and dangerous nature of the opposition candidate… It is already apparent Barry Goldwater is making every effort to adjust his extreme position to one more acceptible. Knowing the short memory span of the average person, it is entirely possible he might succeed in creating a new character for himself if we are unable to remind people of the truth about this man.

This memo is in reference to what's known as the "Daisy" television spot, which was part of what is considered one of the most controversial political television ad campaigns ever. But the campaign's strategies across print media were also comprehensive.

For example, there's the curious case of now-infamous CIA Agent E. Howard Hunt. Remembered by history for his central role in the Watergate scandal, Hunt also infiltrated the Goldwater campaign during the 1964 election cycle and fed information to the Johnson campaign, which could be used to anticipate and counter Goldwater's moves in the press. While it's impossible to take Hunt's statements on the matter at face value — one of his main tasks at the CIA was to create propaganda for domestic consumption, after all — he nevertheless merits a mention here for his documentable multiple connections to publishers which are familiar to comic book historians. Dell, Fawcett, and David McCay Publications are among those who published material (paperback fiction, in the case of Fawcett and Dell) that Hunt wrote himself or had produced via the CIA. Hunt also recruited and supervised comic book publisher Alex Hillman's political associate William F. Buckley, Jr. into the CIA.

Despite the difficulty in separating fact from fiction when it comes to Hunt, his potential influence over paperback and periodical publishers of this period is woefully under-researched. The New York Times got it right way back in 1973: his work is an example of "covertly political novels; propaganda… designed to influence feelings about real events by evoking the unpurged portions of the unconscious", explaining further:

Obviously a vast domestic and international cultural struggle went on, both overtly and secretly; novel against novel, comic strip against comic strip, television play against…. Hunt's books are one manifestation of this struggle; cultural disinformation.

We'll ponder the implications of that rather eyebrow-raising tidbit another time, but suffice it to say that the 1964 election cycle represented a level-up in terms of sophistication and tactics across all media, including print.

"Designed to Effect the Outcome of the Election"

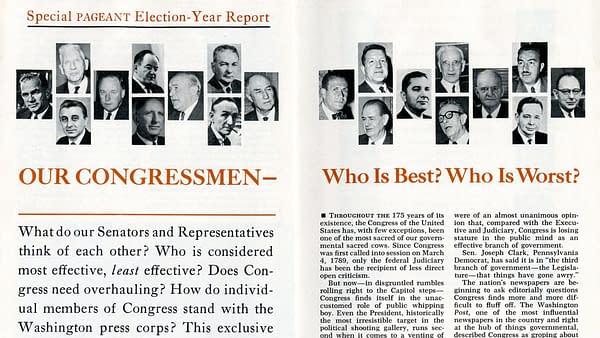

In the middle of this election-year chaos, former MLJ/Archie editor and Madam Satan creator Abner Sundell took part in developing a feature article for Pageant Magazine consisting of a list of the most-effective and least-effective members of Congress as chosen by (as he would later respond to Congressional inquiries) respondents to a questionnaire sent to 100 Senators, 435 Representatives, and 220 members of the Washington press corps.

The poll results were published by Pageant Magazine less than three weeks before the November 3 elections that year. Almost concurrently, the article was excerpted in newspapers across the nation, and reprinted and distributed by various political operatives in numerous Congressional districts — setting off a firestorm of controversy as to the veracity and aims of the poll, followed promptly by a Congressional Committee hearing on December 17, 1964.

As the editor of Pagent, Abner Sundell was one of the people in the crosshairs of Congress's wrath. We have a catch-phrase in the current era for this genre of circumstances that applies pretty well here: Life comes at you fast. One week you're working on a magazine which had by that time become a combination of glamour models, sensationalized politics, and tabloid headlines — as seen through a Beatnik filter — and a couple of weeks later you've got an angry United States Congress Special Committee breathing down your neck in the wake of Lyndon B. Johnson's re-election.

Representative Roman C. Pucinski's (D, Illinois) letter to the Special Committee sums up the thrust of the inquiries:

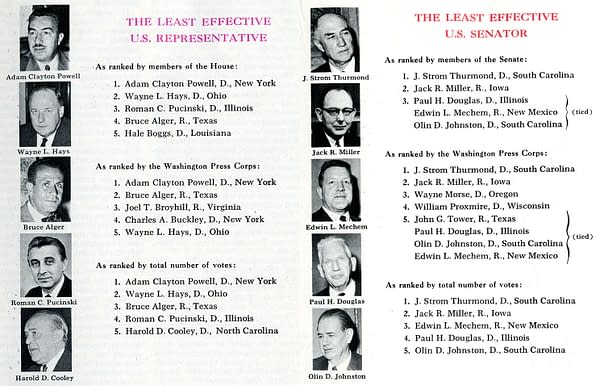

There is no question in my mind that publication of the results of this alleged survey less than 3 weeks before the election was designed to affect the outcome of the election in the districts and States of those Members of Congress involved in the "least effective" category.

I am making this request of your committee because, on the basis of my own inquiries among a large segment of those Members of the House whom I could contact, and on the basis of similar inquiries conducted by other Members of the Congress of the United States and the Washing press corps, I am unable to find a single Member of the Congress or member of the press corps who had participated in this alleged survey.

A reading of the testimony and evidence presented that day leaves one with the almost inescapable conclusion that the poll had been falsified. Of course, the evidence presented is largely one-sided, but that's because the entire staff of Pageant had avoided U.S. Marshalls attempting to serve them with subpoenas to testify.

Comprehensive efforts revealed that no members of the press and only one congressional staffer would admit to answering the poll. In the absence of their live testimony at the hearing, registered letters from various Pageant Magazine staffers including Sundell were introduced into evidence. A prevalent point driven home by many of these letters was that the returned poll forms had been destroyed "to protect the anonymity of participants". Further, the congressional staffer who had previously been identified as responding to the poll flatly denied it under oath — and made the obvious observation that it's unlikely that any member of Congress would vote a colleague of the same party as ineffective for a national media poll in an election year. That line of thinking would make the Democrat-heavy "least effective" lists an odd result at best since Democrats held the majority in both the House and the Senate at that time.

And beyond the poll itself, an analysis of the accompanying article is fascinating when examined in the light of the subsequent 55 years of history.

A quote from Walter Lippmann early on in the article catches my attention: "reason to wonder whether the Congressional system as it now operates is not a grave danger to the Republic."

One of the most influential columnists of the 20th century, we now know that Lippmann was also covertly involved in America's propaganda efforts (pdf) in both World Wars — and beyond. He literally wrote the book on the use of propaganda to further the stability of democratic nations, coining the term "manufacturing consent" in the process. Most infamously, Lippmann utilized his techniques and considerable influence to nudge public opinion towards accepting the internment of Americans of Japanese descent during World War II. At the dawn of the era which led to this 1964 election, he also popularized phrases such as Cold War, and fascinatingly enough helped mainstream the term… True Believers.

All of which is to say that his inclusion here feels like a tell. But is this yet another example of the LBJ campaign's comprehensive efforts to ensure a landslide for Democrats, in the same way that another controversial poll in a publication called Fact Magazine seems to have been? The fact that Macfadden-Bartell publisher Gerald Bartell was then LBJ VP running mate Hubert Humphrey's radio-TV campaign director — and begged off questions about the poll by saying he hadn't seen the data because he'd been on the campaign trail with Humphrey — would tend to support that conclusion.

But an examination of the article itself tells a very different story. The tenor of the piece can be summed up in the undisguised symbolism used to discuss the Member of Congress supposedly named as least effective by the poll:

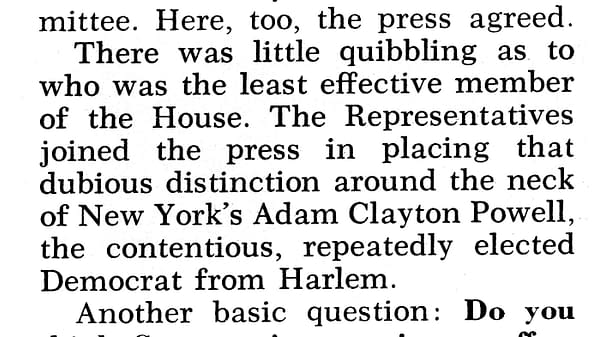

There was little quibbling as to who was the least effective member of the House. The Representatives joined the press in placing that dubious distinction around the neck of New York's Adam Clayton Powell, the contentious, repeatedly elected Democrat from Harlem.

There's no question that the "around the neck" phrasing was purposeful. Powell, the fourth Black person to be elected to Congress in the 20th century, was instrumental in getting an anti-lynching bill approved by the House of Representatives. The bill was defeated by the Senate at that time — and incredibly, similar bills were subsequently defeated almost 200 times in later decades.

Although most of the Senators and House members who testified felt at the time that the Pageant Magazine poll did not affect the outcome of the election, it did create considerable controversy around the country and seems to have been designed to target Congressmen who would create the maximum amount of furor. In addition to the obvious messaging against Adam Powell, the poll also targeted Senator William Proxmire (who replaced Joseph McCarthy upon that Senator's death, and angered many by breaking with protocol and calling the notorious Senator a "disgrace to Wisconsin, to the Senate, and to America"), Wilber D. Mills (Arkansas Democrat who chaired the House Ways and Means Committee), Hale Boggs (House Majority Whip), and the always-controversial Senator Strom Thurmond.

If the poll seemingly had little hope of changing the outcome of the election of such individual members of Congress, what was its goal? A reading of the article itself in the context of subsequent political history leads to some possible conclusions. In addition to the attack on Powell, the article hits some very specific themes in regards to Southern Democrats:

Thus ten of the 16 standing committees in the Senate are headed by veteran southern [Democrat] Senators, who rarely have more than token Republican opposition at the polls. Critics of the seniority rules are quick to point out that the 39 states not in the South hold only six chairmanships.

More or less the same situation applies to the House. Several key committee chairmanships are held by southern Democrats, including the powerful Ways and Means and Armed Services committees.

Many lawmakers were in favor of a change in the rule permitting unlimited debate in the Senate — a rule that enabled southern Senators to stage a two-month talkathon on the Civil Rights Bill before the rest of the Senate, in an historic move, voted 71 to 29 to invoke cloture and shut off the flow of windy rhetoric.

An Alabama lawmaker said "Rule changes are not needed to make for a better job by Congress. Less pressure from minorities would be instrumental in getting legislative programs acted upon."

A New Jersey Representative said, "You may think I am being facetious, but I would say a change in administration and for the first time in years and years have a Republican majority."

That supposed New Jersey Representative didn't get his wish in 1964. LBJ won the presidential election by a record margin, and gains in both the House and the Senate maintained a supermajority for Democrats in Congress. The subsequent era saw the passage of Medicare, Medicaid, the Voting Rights Act, and the Fair Housing Act.

That level of mandate from voters perhaps made this Congressional Committee in December 1964 less attuned to some of the details here than they otherwise might have been. For example, this election was the first since the 1870s for which Republicans dominated the deep South. And then notably, Thurmond switched parties to become a Republican after this election and went on to become the longest-serving Republican member of Congress in U.S. history. Senator Lindsey Graham is the successor of Thurmond's South Carolina Senate seat.

The Pageant Magazine article's focus on Southern Democrats and its virtually undisguised commentary on race, along with Goldwater's rally tactics in the South, lead one to one possible conclusion. The Goldwater campaign of this election cycle brought the dawn of what later became known as the Southern Strategy. With the benefit of hindsight, aspects of the Pageant Magazine controversy feel like a harbinger of things to come.

In the interest of completeness, I should note that Barry Goldwater and one of Abner Sundell's former employers, John L. Goldwater (the "J" in MLJ/Archie) were typically described as "distant relatives" in mainstream media reports over the years, though I took a quick glance at ancestry.com and didn't spot the connection. In this case, it's unlikely to be meaningful in any event — except in the broader sense that some of the other connections presented here likely are: print media was both much more influential and a much smaller world 50+ years ago. Familiar and forgotten comics publishers like Fawcett, Dell, Hillman, Ace, Martin Goodman's various imprints, and countless others developed highly successful paperback and magazine lines. Such conditions are likely to lead to strange connections and alliances, both intended and otherwise.

Gerald Bartell's motivations for seemingly going against his party in this controversy never became clear, and the 1964 election matter quickly vanished amidst what became a series of controversies that both he and Pageant Magazine seemed to generate. For example, in 1968, Pageant found itself a target of federal prosecutors for a story that year that boldly promoted a cure for cancer invented by the Rand Development Corporation (not to be confused with this other RAND Corporation). And just because this story isn't strange enough… yes, Rand Development Corporation was subsequently shown to have numerous documentable ties to the CIA.

These bizarre twists and turns that Pageant took through the 1960s also bring the road not traveled to mind: EC Comics and Mad Magazine founder Bill Gaines would later state that Pageant had offered comics industry legend Harvey Kurtzman the job of running the magazine as its editor. Gaines said he changed Mad's format from a comic book to a magazine in part to help him retain the astoundingly talented Kurtzman.

That also provides some context for the magazine choosing another editor with deep comics industry experience in Abner Sundell. Throughout the country's earlier history, cartoonists had done much to shape public opinion about politics and current events. For example, comic artist Thomas Nast was likely the most formidable political commentator of the 19th century. That print media seemed to be looking to expand that sort of meme magic beyond the panel border a century later is perhaps unsurprising.

"I Got to Wondering was it Worth it"

Former comic book publisher Alex Hillman died in 1967, having amassed a stunning and world-class collection of fine art including works by Matisse, Braque, Miró, Manet, Renoir, Degas, Toulouse-Lautrec, and Picasso. In 1984, The New York Times noted that Hillman "came to art collecting through the artists that he, as a publisher, commissioned to illustrate new editions of the classics".

In the 1970s, Hillman's wife Rita Hillman was sometimes described as one of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis's closest friends. One news item from the era has a reporter rather breathlessly noting that Hillman's arrival at an event invariably means that Jackie must not be far behind. It's hard to know what to make of the wife of one of the architects of modern American conservatism being pals with the wife of one of the most revered Democrats in American history, except perhaps that it proves that "politics makes strange bedfellows" cliche once again.

One of Hillman's legacies, the Rita and Alex Hillman Foundation, contributes grants in the areas of medical science and health care to this day.

As for Abner Sundell, all of this begs the question: did the original managing editor of MLJ/Archie, creator of Steel Sterling and Madam Satan among others, and the editor who helped oversee the debut of Archie and his gang knowingly play a contributing role in a political propaganda campaign that would presage something notorious in subsequent years?

While that's far from clear, the circumstances are eyebrow-raising. Evidence presented that day in December 1964 revealed that the original draft submitted by a freelance writer was substantially altered at the Pageant Magazine offices — notably, the "placing that dubious distinction around the neck of New York's Adam Clayton Powell, the contentious, repeatedly elected Democrat from Harlem" line was added at the Pageant offices, according to the Special Committee report. Not by Sundell, but it happened on his watch. All told, it's hard to imagine that he didn't have a sense of the methodology and intent of this piece in one of his magazines.

And ironically from the present-day perspective, the same pre-election issue of Pageant also contained a piece called "Farewell, Paper Ballots", which noted the gradual rise of mechanical voting machines while waxing nostalgic about what good fun could be had by making funny remarks on hand-marked paper ballots. While admitting that this could lead to ballots being thrown out, the piece concluded "And truthfully, nobody was really ever harmed by what was clearly innocent fun."

That said, sifting through the available evidence, it also seems clear that Sundell's superiors at Macfadden-Bartell had nudged their managing editor into being the public face of the controversy. He was the one answering angry letters from powerful members of Congress and getting torched in newspapers around the country. The big picture here — as much of it as I can see, anyway — leaves me with the impression that he may have been tip-toeing among the political giants of his era, was pulled into something over his head, and found himself hoping not to be noticed too much. He still likely deserves a portion of the responsibility for the 1964 Pagent controversy, as it's difficult to get around the fact that he was the magazine's editor.

Still, a subsequent news story seems revelatory in this regard. The controversy took its toll on Sundell, and he had resigned from Pageant Magazine by the next summer. He then announced to great fanfare in the press that he intended to become a painter. Sundell's surprisingly raw stream of conscious statement to an AP reporter in 1966 feels like an account from someone who'd gone through something and was unburdening himself:

"I got to wondering was it worth it", he explained. "I used to sit on the commuter train and ask myself why — why the hell am I killing myself."

"…seeing my blood pressure go way up, working until 8 or 9 or later every night, watching my relationship with my family deteriorate, all kinds of pressures. You lose your freedom of choice, freedom to do and be what you want. It's a rat trap. You have to cut it off, live with yourself, measure up to your own values."

"You know, it's the old question, what have you ever done in your life? What good are you? At some point you have to answer it. And this way I can answer that maybe I've added a little beauty, a little joy."

"[My boss] was surprised all right, but he could see my point. He knew I had to do this thing. I had to really live before it came my time to die."

It appears that Sundell didn't quite make it financially as a painter. Keeping a relatively low profile, he returned to publishing-related endeavors a short time later. Among other things, he collaborated on two art history books — Art in America: from Colonial Days to the 19th Century, and Modern Art in America — which are widely referenced in educational and history texts.

As if attempting to answer those "What good are you?" questions he posed to himself in 1966, Sundell seems to have lived out a portion of his later years traveling and painting. Attempting to add "a little beauty, a little joy… before it came my time to die."

If Abner Sundell ever explained what exactly did happen in 1964, I've yet to find a sign of it. But perhaps he just poured all that frustration and stress into his art. A critic at a gallery showing of his work once said:

There is a frank admission of his sources in the past, yet these have been assimilated and absorbed into a personal expression. Evident in all these pictures is a single point of view, a common vision. They are the work of a sensitive man, who has found his means of expressing his responses to the visible world.

As far as I can tell, this writer and editor who played an important role in the early comics industry at Archie and beyond, never connected with fandom as it began to boom in the 1970s and beyond.

Abner Sundell died in 2001.