Posted in: Comics | Tagged: before watchmen, Comics

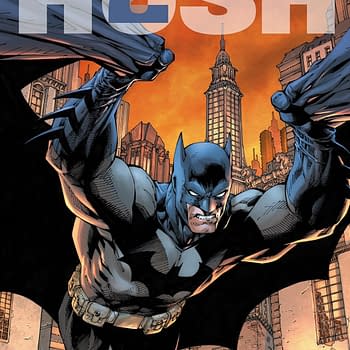

Defending The Indefensible: Before Watchmen

The world hadn't seen a comic quite like Watchmen until it first hit the stands. While it wasn't the first comic to posit that the men and women behind the masks had their own personal failings, it was one of the first to do it in a capital-L "literary" way. It appears on Time magazine's top 100 novels of all time alongside works by James Joyce, Ernest Hemingway, and Kurt Vonnegut. In a medium historically dismissed as kiddie stuff, Watchmen popularized a new intellectual standard for comics. For a lot of people, Before Watchmen is a violation of the canonization of the original classic.

Dave Gibbons recently made a few headlines when he said Before Watchmen was "really not canon." Alan Moore turned down a "couple of million dollars" to give the prequels his blessing.

That's fine, it's evident the creators involved in Before Watchmen project aren't trying to write Watchmen 2.0. They're using their talents to produce an inventive and cutting-edge elaboration on the original series. They're good comics, plain and simple.

My favorite part of Before Watchmen thus far is in Nite Owl #2 when Dan Dreiberg gets bitten by a radioactive owl and decides to devote his life to fighting crime. Or maybe it's in Doctor Manhattan #1 when a young Jon Osterman high fives Robert Oppenheimer, changing the lives of both men forever.

Neither of these things has happened. But if you ask a lot of comic readers out there, this is about what they expect out of Before Watchmen.

However, comic fans who pick up these books with a bit of good faith and optimism will find their interest rewarded.

Before Watchmen doesn't play fast and loose with continuity—that's not its purpose. These books are executed with a certain liberty from their source material. The creators are forced to walk a tight rope of allegiance and respect to Watchmen, while still making the books their own. Any misstep is glaring. But when handled correctly, they're simply great comics.

It obviously helps that these are some of the most reliable and foremost talents working on comics today.

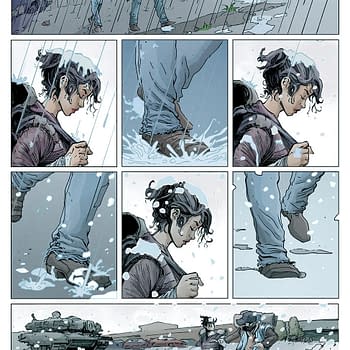

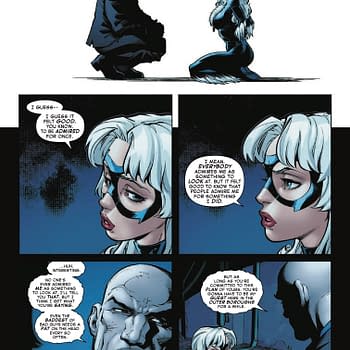

Amanda Connor's art on Silk Spectre is arguably the best artwork of her career thus far. The first issue takes on the feel of Archie Comics as teenage Laurie Juspeczyk tries to formulate her own identity in the overbearing shadow of her not-so-gracefully aging former superhero mother. In Darwyn Cooke and Connor's script, Laurie daydreams throughout the issue. This is something you'd never see in Watchmen, but it works wonderfully.

Cooke's own Minutemen is essentially Watchmen: The New Frontier. The actual content is taken mostly from the excerpts of Hollis Mason's Under the Hood included in the first three issues of Watchmen. Cooke is able to take this well-established history and present it in his own acclaimed style. I can think of no one better to be making this book.

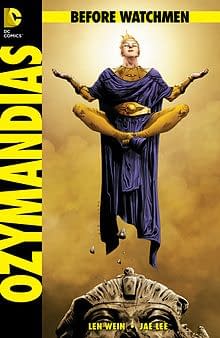

Ozymandias reads like a tribute itself, but not to the work of Moore and Gibbons. Len Wein's epically pompous script and Jae Lee's statuesque artwork combine to form a comic that reads more like a nod to Herodotus than anyone in the comics world. And it's still based firmly in the established continuity: the book takes most of its schematic content directly from an Adrian Veidt monologue in Watchmen #11. Despite its relatively direct adaptation, Ozymandias has been an inventive and highly enjoyable title.

Another thing that works well is that Before Watchmen isn't really a mini-series. It's seven separate mini-series under one banner. There's no continuity raised, say, in Silk Spectre #2 that you have to know to be able to understand Rorschach #1. This shows remarkable restraint by DC—ever lovers of the event, the crossover, and the tie-in. So if you wanted to skip reading Nite Owl (arguably the weakest of the bunch so far) altogether, you're still perfectly able to enjoy Minutemen. DC has, however, included a largely ignorable incentive to pick up every issue.

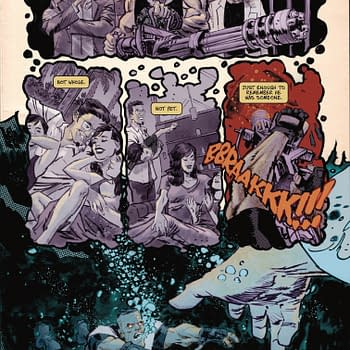

The one stab at linking each title is Len Wein and John Higgins's The Curse of the Crimson Corsair, an attempt to produce a tribute to Tales of the Black Freighter in the original Watchmen. Black Freighter worked in Watchmen because it mirrored the various ongoing schemes at play. CrimsonCorsair doesn't have anything to do with the books in which it appears. The purpose Black Freighter served is completely ignored here. It's a pretty pointless endeavor.

A few other tropes efficiently spread across Watchmen have popped up at the forefront of these books, causing me to question if perhaps a little more cross-editing might have been a good thing. BDSM (a slight theme in Watchmen) seems to have shoehorned itself into most of these titles rather prominently as source of thematic gravity. By the time the topless dominatrix villainess (mentioned in Watchmen) appears in Nite Owl, the whole thing feels pretty goofy. And how many times can Moloch pop up? But in the grand scheme of the project these are slight quibbles.

Before Watchmen is something largely different from the average superhero book on the stands and it's something special. It's A-list talent doing something new with a revered mythology. They might not be completely perfect and they certainly aren't Watchmen, but that doesn't mean they're not worth reading. The quality is there and the books are getting made regardless of the arguments. I see no reason not to take a look.

If you see the Comedian having a drink with Lenny Bruce, you may consider everything I've said here null and void.

Tom Gronkowski spent five years at the front lines of comic book retail. He lives in Chicago, Illinois. This is his first (hopefully, of many) contributions to Bleeding Cool.