Posted in: Comics | Tagged: Alan Moore, brian bolland, Comicraft, Comics, dc, elephantmen, entertainment, John JG Roshell, killing joke, lettering, marvel, richard starkings

From The Killing Joke To Age Of Apocalypse – Richard Starkings And John JG Roshell Talk Twenty-One Years

Ferran Delgado: Richard, When did you start to appreciate the lettering art? Was it your main interest or just one of the creative process behind a comic book?

Richard Starkings: I remember as a kid reading Marvel UK Spider-Man reprints and noticing Artie Simek's little outline capital letters in caption boxes… I didn't know they were called Drop Caps back then but I appreciated that they were cool looking and somehow added to the overall reading experience. Any time that kind of subtle addition to the pleasure of reading a comic book is present, I'm aware — especially now — that all the creators working on the book are having fun and feel free to do so. I've worked with creators and editors who rein you in when you're having fun, and it's usually a sign that the book is going to look boring. I've always loved all the elements that we tend to think of as Lettering elements — cover copy (IN FINAL BATTLE!), sound effects (KRAKATHOOM!) title pages (THIS MAN! THIS MONSTER!) and footnotes (*See ish 36 of Spidey, continuity vultures!) — and consider them essential to comic books as an artform.

FD: How did you start to work for Marvel UK, and how did your role evolve while you were there?

RS: I was hired to do design and paste up on Spider-Man Comics Weekly and then Secret Wars. I was also happy to take home as much freelance lettering work as they could throw at me. Marvel UK is best remembered now for Transformers, Doctor Who and Captain Britain but the bread and butter publications in the 70's and early 80's were weekly reprints of Marvel US superhero titles. Transformers was so successful — outselling 2000AD at one point — that it was necessary to generate original material so we didn't run out of material from the US. That opened up opportunities to generate original material for other weeklies such as Action Force –– GI Joe for Brits — and The Real Ghostbusters. I was given editorial responsibility for Action Force and then Ghostbusters, which proved very successful and earned me the trust and respect to do wholly original titles such as Dragon's Claws, Death's Head and The Sleeze Brothers. I was also the editor of the Doctor Who comic strip for two years and wrote, and lettered, strips for Doctor Who, Ghostbusters and, my favourite, Zoids!

RS: Yes, I think that The Killing Joke remains the work with which I'm most proud of being associated, and probably my best work as a pen lettering artist. James Hill, a writer who was working with me on Thundercats, asked me what my dream lettering assignment would be and I answered, "Script by Alan Moore, art by Brian Bolland," I think I added that it would never happen, so when it did, I just had to offer my talents to Brian when I found myself sitting alongside him at the Birmingham Comic Art Show in 1985 or 86, I think. He was great, and it was largely down to Brian that it actually did happen. Working with him was a joy and one of my fondest memories of working in comics. At around the same time I was lettering Detective Comics for Alan Davis and Paul Neary, and I learned a great deal from both of them as well. I feel very, very fortunate to have worked with so many heavyweights in my field on both sides of the Atlantic. I also benefitted from working under the tutelage of Steve McManus, Simon Geller and Robin Smith, who gave me enormous amounts of feedback and encouragement when I was still very wet behind the ears. I was very lucky. Did I already say that?

FD: What pushed you to cross the ocean to NY and afterwards, to LA? Did you feel that it was a backwards step to work as a letterer after your experience as group editor in Marvel UK?

RS: I wasn't pushed — I was pulled! I chased a girl out to California! We broke up after a few months, but I realized that America was the right place for me to live and grow in my career. I was able to do so because I could earn money as a freelance letterer and that kept me involved in comics until I found work at Graphitti Designs in 1990.

That said, I never think lettering is in any way a backwards step if I'm working on a project involving creators who are passionately committed to their book. I love the collaborative process of making comics and seek it out whenever possible. Because of my background in editorial, I never thought twice about picking up the phone and talking to the writers and artists with whom I was working. That to me is very much the joy of working in comics — bringing different skills to the table and bouncing ideas back and forth. Working with Joe Madureira on Battle Chasers, J Scott Campbell on Danger Girl and Tim Sale and Jeph Loeb on Batman Dark Victory, Spider-Man Blue and Hulk Gray were high points in the 90's and early naughties. Very exciting.

FD: When did you first start working with a computer? What pushed you to get in the digital world: a new challenge or a need for shortcuts to improve your quality of life?

RS: I had made attempts to work with PCs before finding myself at Graphitti Designs in Anaheim, where the Mighty Bob Chapman was working with a Mac to create his Shirt Tales newsletter. He reluctantly taught me what he could about Quark Xpress and allowed me to create bits and pieces on the Mac for shirt designs and books. I was amazed at how intuitive and easy it was to work on a Mac and around that time I noticed that John Byrne was working with "computer lettering" on Namor over at Marvel. That to me was "the pen lettering on the wall." If artists were working with fonts, my days were surely numbered.

I ran into Byrne at San Diego Comic Con that summer and grilled him on how he was creating fonts and applying the lettering to his artwork. I think I bought my first Mac — a IIci — and a monitor, keyboard — they used to be sold separately — and printer that Fall. I think they cost me $4500 back then. I maxed out my only credit card. I was committed.

FD: What did you think about Batman Digital Justice by Pepe Moreno done 100% with computer including lettering in 1990? Did it influence you somehow? Who was the first one to letter digitally in American comics?

RS: I was aware of it, and I was aware of Shatter by Michael Saenz.They really didn't register with me, although I recognize both Pepe and Michael as pioneers of digital art. However, both books had a very specific "digital" bitmapped style; what I wanted to replicate was the pen-lettered look of comic book lettering. In my mind, the first person to do that was David Cody Weiss who created a font to letter a Shadow graphic novel for DC back in the 80's. I think that preceded Byrne's lettering fonts.

FD: What was the reaction of the editors to digital lettering?

RS: Hesitant to say the least. Very early on, after I'd lettered two pages at the back of an issue of X-Factor with my first font, Bob Harras called me and told me never, never, to letter any X-titles with computer fonts. That didn't stop me, and a couple of years later we were lettering 17 X-Men books in one month, with "computer fonts." I was very lucky, again, to have enthusiastic support from editors Gregory Wright and Rob Tokar; they were very open minded and helped me troubleshoot the early versions of my font.

FD: What was the reaction amongst other letterers?

RS: Mostly Fear and Loathing! I don't think they were worried at first, but as time went on and my digital work improved, I started getting concerned phonecalls from pretty much all the top letterers at Marvel and DC. Letterers like Phil Felix, Bill Oakley and Todd Klein had a very complimentary and interested approach; others either acted as if I was, in the words of the late, great Mark Gruenwald, "the anti-christ!" and refused to acknowledge me, or sought to undermine my studio's success by stealing away employees or trying to replicate the Comicraft setup. When Robin Spehar, of Dreamer Design, started up his digital lettering shop, I made a very conscious decision to extend the hand of friendship to him at Comic-con that year, one which had been denied to me by the leaders of the Old Guard.

FD: What motivated you to hire an assistant?

RS: The first assistants I hired were the roommates of the wonderful Neil Sofge, the guy who was helping me learn Fontographer. I basically needed help inputting scripts, and I hired Janie — I forget her last name back then but she's married now to former Top Cow editor and writer Dave Wohl — and Brett Sonenschein. Learning all the various Mac programs — and dealing with the dreaded bomb that came onscreen every time the system crashed — was taking up enormous amounts of time, so getting help with typing in scripts was a huge help at that stage.

FD: Why didn't you restrict the volume of work you could handle?

RS: As any lettering artist or freelance artist knows, volume of work and meeting deadlines don't always work well together. I didn't want to have to work through the night or rush my lettering to meet an unreasonable deadline, as I had had to when I lived and worked briefly in New York. Having an assistant taking care of ruling panel borders, cutting out and pasting lettering onto the physical artwork — which we were still doing as late as 2001 — and making Fedex runs eased the pressure on me, and allowed me to take more time on title pages, cover lettering and other aspects of graphic design which I had grown used to doing at Marvel UK.

FD: How do you think your life would be different if you hadn't hired assistants and expanded the Comicraft studio?

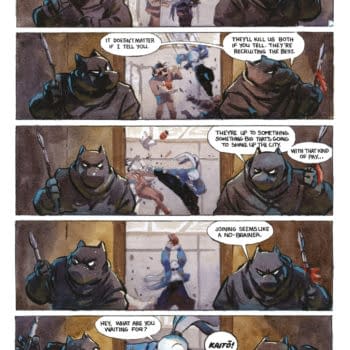

RS: Well, I don't think I would have spent many more years working alone lettering comics, if that's what you mean? Again, I enjoy the collaborative process. It was fun working on staff at Marvel UK, it was fun working at Graphitti Designs and I had enormous amounts of fun running the Comicraft Studio. Creatively it was one of the most rewarding periods of my life. I have been described as a Mover and a Shaker and I guess that's true — I don't like to sit still, I like to make things happen and see things move, change and grow. Right now I enjoy working with Axel Medellin and other artists on Elephantmen; I love going to shows and hand selling my Elephantmenbooks, meeting people who dig it and meeting other creators who are doing their thing.

As a group editor, I had worked with a staff of nine people at Marvel UK, so it was easy for me to take in work and operate a studio. I don't think I consciously sought to expand, but as our fast turnaround time and high quality grew more popular with writers, artists and editors, I took on letterers as our workload increased. John Roshell was the first guy I hired and he was sometimes reluctant to see the studio grow, but as it did, it allowed him to focus on font, logo and publication design, which kept him growing and learning and kept him interested. We hired Dave Lanphear away from Malibu Comics and his skills and abilities allowed us to take on a large volume of work from Acclaim in the late 90's with which I was only tangentially involved. Dave was a pen lettering artist who learned digital lettering very fast thanks to our studio setup, and really there was nowhere else to learn those skills back in the 90's.There are still a lot of letterers working in comics today who acquired skills at Comicraft — Dave, Troy Peteri, Wes Abbott and Saida Temofonte to name a few.

All in all, we hired maybe 30 people over a ten year period, with never more than 16 people working in the studio at any one time. We were always crazy busy and we all learned a lot very fast, through necessity. My goal was never to keep things that way in perpetuity, very early on I wanted to work towards self publishing fonts and comics. Comicraft was a rewarding way to reach that goal. I modelled the Comicraft studio on Studio Hergé, which took in advertising work in order to support the creation of Hergé's TINTIN comics.

FD: How do you think the lettering world would be different if you hadn't created Comicraft?

RS: Someone else would have done it; I was just the quickest to bat, and perhaps the most passionate about it. John Roshell matched me in enthusiasm and spurred me on, but if we hadn't figured out all the mechanics and tiptoed through that creative minefield, someone else would have, I'm sure. But they didn't! We did! Huzzah for us!

FD: John JG Roshell, when and how did you develop an interest in typography?

John JG Roshell: I was pretty young, maybe six or seven, when I started recognizing typefaces, seeing the same ones on store signs and package labels. In my teens, I thought the font Stop was the coolest thing I'd ever seen, and made a couple of attempts to re-create the rest of the alphabet from the few letters I knew. Which isn't much different from how I create fonts now — most of them start with a handful of letters from an initial idea or a logo, and then I have to figure out how the rest of it will work.

Soon after that I discovered Letraset rub-on letters, and used Eurostile (because what's better than Eurostile? Nothing) to create flyers and stickers for my band and for cute girls who were running for student office. Yes, it's true, you can be a font geek and get girls! Or at least talk to them.

FD: How did you meet Richard, and were you doing at that point in your life?

JG: I was just out of UCLA with a degree in design, and was working a couple of part-time jobs, trying to figure out what to do next. Richard's friend Marc Siry, later of Electric Crayon fame, called my girlfriend looking for someone who could type up scripts into QuarkXPress for Richard. I heard her say "…you want me to letter comic books?!" and practically tore the phone from her hand. "Hi! I love comic books! Can I work on SPIDER-MAN?" Richard hired me anyway.

I had a couple of years experience using Illustrator, Photoshop and Quark on the Mac, but when Richard introduced me to Fontographer — just to see if I could fix a troubled "8" in his font — I took to it like crazy and started digitizing all of his pen lettering styles and more. Creating my own fonts? It was like a dream come true.

Oh, and the girlfriend married me anyway, too.

FD: What were your professional goals before you got involved in Comicraft?

JG: Rock star. Lead guitar. Or rhythm. I wasn't picky.

FD: When did you discover the work of the great masters of comic book lettering?

JG: I was indeed a Spidey fan growing up, so I pretty much equate comic book lettering with Sam Rosen and Art Simek, though I wasn't really aware there was such a job, or even had any ambition to work in comics, until the day Richard called. I still have a real soft spot (as you can likely tell) for the '60s and '70s Marvel look that Art and Sam's work defines.

Richard turned me on to Tom Orzechowski, who is pretty much the master of fitting maximum text in minimum space with style. And I remember early on in the Comicraft days, Richard and I stopping work one afternoon just to pore over Todd Klein's beautiful calligraphy in Sandman #50.

FD: What is the origin of the Comicraft name?

RS: When I lived in Venice Beach, one of my roommates, Griff Rowlands, was a carpenter, in fact he has since built all the beautiful shelves in the Comicraft Studio… He had a business card at the time upon which was written his business name, "Proudcraft." When JG asked me how he should answer the phone, I threw out "Comicraft," and it stuck.

FD: Your growing library of fontstyles allowed you a versatility that must have been a dream come true for editors, because they only needed to deal with just one team instead of multiple letterers, and your work could match perfectly the style of any artist. Did your experience as an editor help you understand the needs of an editor?

RS: Sure, but I think primarily understanding that an editor only needs to know that his or her book is your number one priority and that they would get it tomorrow – or even today now that shipping lettering is all digital too – was the real key. Editor Greg Wright had a sign in his office that I took to heart – "Courtesy means Business and Business means your job!" No matter what your role in the comic book making process is, the most important thing is communication; courteous communication. Having lots of different fonts, and being prepared to make new ones also helps.

FD: What did you think about Gaspar Saladino's work in Batman: Arkham Asylum? He did a terrific job giving different voices to the main characters, merging perfectly with the stunning art by Dave McKean. Did he influenced you to work on this direction or did you have other references?

RS: I was originally slated to letter Arkham Asylum, and before that, Black Orchid, as I'd got to know Dave McKean at the Westminster Arms meets in London. I even lettered most of the first issue of Black Orchid before letting Karen Berger know I couldn't finish it. I was just about ready to leave London for New York, so it was the right decision for me at the time. I love both Dave McKean and Grant Morrison's work but neither Arkham Asylum nor Black Orchid were the kind of comics I enjoy lettering. They were very introspective comics, very controlled. I do think Gaspar is one of the top letterers in comics, and I thought he did a great job on Arkham Asylum, but I wouldn't site him as an influence — Orzechowski, Simek and the Rosens were much more important to me — Marvel letterers!

FD: JG, very early on you specialized in typographic design, full package graphic design and web design, you weren't just lettering comic books. How did this splitting of assignments with Richard come about?

JG: As we got onto better-selling titles, the stories we lettered were getting re-packaged in terrible-looking paperbacks. I kept telling Richard, "we could design them so much better than this!" so he pestered editors until Mark Powers finally gave us a shot on the first edition of the X-Men: Mutant Genesis trade, and once we broke through that wall we started getting a lot more.

Around that same time, Kurt Busiek came to us looking for help in assembling Astro City from the ground up. So we got to establish the look of the series, from logo to lettering fonts to letters page, and it was a ton of fun.

FD: What is your criterion for designing fonts? Do you try to recreate specific comic book lettering styles from different eras, or do you try to create a diversified catalog of as many styles as possible, or did you simply create what you enjoy?

JG: All three, really! Early on, everything came out of need — we need a title font for Batman, or J. Scott Campbell wants a handwriting font, or we're redesigning the X-Books — so I was constantly cranking them out just to keep on deadline. I still have folders of Illustrator files of letters, and half-finished fonts, so sometimes (like recent releases KillJoy and KillSwitch) I'll browse through those and work on a few until something gets rolling. I also keep an eye on what we've released recently, and try to keep a balance between the different styles and categories, to hopefully keep things interesting and useful for our customers.

FD: You went through a stage wherein you worked with 3D programs, designing logos of the Annuals in 1995 and the A and X icons for the corner boxes on the Marvel books. What pushed you to explore this technique, and what was the reaction of editors?

JG: I think we did those just because we could, to a certain extent. There was an urge to show that we could not only re-create comic pen lettering as it had been done, but to do things that no pen ever could. So it was showing off, but it was also pushing the limits of where digital lettering could go. And sometimes you have to go too far to find where the sweet spot is.

FD: Why did you stop it?

JG: Oh how I HATED working in those 3D programs! I never could get the feel for controlling 3D space on a 2D screen. I would get everything to where it was lining up almost right, then rotate the view a few degrees, and discover objects were actually miles away from each other. It was maddening.

I also don't recall there being any great demand for them after that initial push. There was definitely a backlash against computer lettering in general — we were regularly accused of "ruining" comics…fortunately this was pre-internet days. Still, I remember telling Richard, "don't worry, someday people will be nostalgic for Comicraft lettering," and lo and behold, it's true today. We have people come up to us at comic cons all the time now who think our work on Age Of Apocalypse was the greatest thing ever.

FD: You've often designed the full package of a few of the Hero Initiative and CBLDF editions. Why do you give support to these projects, and what do you think that they contribute to the industry?

JG: It's so easy to get totally wrapped up in your own thing and forget about everybody else, so it feels good to be able to contribute my abilities to serving a greater cause once in a while. Plus they're fun — the HERO and CBLDF people are some of the nicest people in comics. Although, nearly everbody in comics is nice, actually.

When and why did you make the jump to web design?

RS: JG had learned HTML in order to publish promotional materials for his self published Waste LA comic book online. Shortly thereafter I think we started building a website to sell our comic book fonts online too. In the late 90's, Kurt Busiek asked me if we could help launch Gorilla Comics with a website and email newsletters and I think an online forum, so, of course, I eagerly volunteered JG! I think that was a great learning experience for both of us. It made no financial sense whatsoever, and in fact, Gorilla did not last very long, but Kurt is always an enthusiastic and patient collaborator, so it was a great experience and I think JG learned a lot about web design do's and don'ts.

FD: Did you consciously want to break your dependency on comic book lettering — were you deliberately seeking out new challenges?

RS: Yes, definitely, both JG and I don't like to sit very long on our laurels… but we have also been very fortunate to have people like Kurt and Jeph Loeb and J Scott Campbell pushing us and pulling us along. Jeph arranged for us to build the website and forum for the Heroes TV show and that led to work with Tim Sale on the show itself, and around the same time we started publishing Hip Flask, Strange Embrace and Tim Sale's Black And White. Never a dull moment!

FD: Do you have opportunities to work closely with artists as Richard did on Daredevil: Yellow, whereby Rich lettered the splash page and credits before Tim Sale penciled the page?

RS: That was a very specific situation wherein Tim wanted the look and feel of the credits he liked in an old Steranko book, SHIELD, I think. It's fun when artists have a very specific idea about what kind of lettering they want for their book, because you know that they're aware that the lettering is part of the package. When I was working on a run of Xtreme X-Men with Chris Claremont and Salvador Larocca, I designed a fancy little creators credit box for them… I'm not sure if they appreciated it, but, Kurt Busiek called up and said, "Hey, I want one of those for Avengers!" Those are fun little things, I always enjoy titles and credits and tag lines… they help create the grandeur and melodrama of comics, it's a shame we don't see them too much any more. There are plenty in Elephantmen. I consciously use all the various tropes we associate with comics — sensational next issue pages, cover copy, thought balloons, sound effects. Comics should be fun!

FD: You put a lot of emphasis about how lettering directs the reader across a page, but when the artist designs the page, he also considers a path for the reader's direction. Do you think that both paths might clash? How do you solve this problem when it appears, if it appears?

RS: All disciplines in comics serve the same purpose — telling the story. Tim Sale actually told me one time to cover the back of the head of a character, he didn't care. Often times I would go out of my way to stay off figures and heads, but Tim saying that made me re-think that philosophy. The best place for lettering is the place that serves the story, and I definitely enjoy the push and pull between words and art; a comic isn't really a comic until it's lettered, until the words and pictures are joined together. I enjoy being in the position of joining those elements and helping direct the reader across the page, but as a lettering artist, you really do need to seek out and complement the intentions of the artist and the writer on the book. Alan Davis once pointed out to me a sound effect — drawn by another letterer — that suffocated one of the panels he'd drawn. Alan gives a lot of thought to the placement of lettering in his work and more often than not draws the sound effects himself so that he has total control over how much of his art it does or doesn't cover. I totally understand that and try to be as considerate as I can to all the storytelling elements in every panel.

When I letter Elephantmen, it's great to be in the position, as a writer, of reworking lines and adding sound effects in reaction to what the artist has drawn. When I worked as an editor and letterer at Marvel UK I often tweaked the writing as I was lettering it, and some writers I've worked with, who have come to trust me, encourage me to tweak or edit captions and dialogue if I see something that doesn't work or flow. I don't recommend letterers do this, but I do consider it to be part of a vital collaborative process. Most of the projects that I've worked on that were successful were created by teams who valued all creative input and saw the work as something that could always be polished or improved.

FD: Have you ever been in a situation whereby an editor or creator restricted or controlled your input?

RS: Many, many times… there was one particular writer who wanted no variation in size or emphasis on bold words or exclamations, another who wanted no emphasis whatsoever, and an editor who mailed me a two page letter because I changed the placement of ONE balloon. Good Grief! But I think you're referring to the edict made by the publisher at Marvel some years ago… all balloon and caption lettering had to be Upper and Lower Case, rather than ALL UPPER CASE. He felt that the Upper Case tradition made it look like everyone was Shouting, and that Upper and Lower Case was more mature like proper books for adults. To my eye, the lower case lettering looked more childish.

At around that same time, cover copy was dropped completely and title pages were replaced by story so far pages. For my liking, these were all terrible decisions akin to telling TV producers to drop title sequences and theme tunes and tell the actors to talk in a monotone. But that's just me, I'm sure everyone else thought it was a great idea, right?

FD: You mentioned in the past that Brian Bolland gave you the chance to pick out a couple of pages of original art from Batman: The Killing Joke, spectacular collection of original art. Can you tell which are your favourite pieces and why did you decide not to make them public?

RS: This is one of those questions I'm asked the most — "Do you own any of the artwork from The Killing Joke, and are you willing to sell it?" Sadly, I sold the page I had, the penultimate page on which The Joker tells The Joke, many years ago. The other page I had, the one where Batman smashes through the mirror toward The Joker, I'd traded with John Higgins, the original colourist on the book, for the colour art of the other page I had. I still have an original piece Brian created for me of Hip Flask, though, and Brian created a beautiful digital cover for Elephantmen #3 for me. My feeling in regard to original art is that we are all merely holding them for a short while as they make their way across the decades into museums and art galleries. I have some pieces of original art, but they are all Elephantmen pieces that have yet to realize their true worth!

FD: In the past, pen letterers had the privilege to work on and enjoy the physical pencil art before it was inked. Did you have the time and opportunity to make xeroxes of it? I imagine a full set of pencils of The Killing Joke, and I start to drool. Since Marvel released a few editions of issues in pencil form in the 90's and DC recently published the pencil version of Batman: Hush, maybe they could produce a new pencil edition of The Killing Joke?

RS: I had the opportunity to make xeroxes, but not the foresight! Joe Melchior, Brian's agent, knows that it might be possible to track down Brian's thumbnails for the book, but I'm not sure Brian made copies of the actual pencils. I have a set of A4 high quality xeroxes of the inked book, which I have kept carefully for all these years, but I didn't even keep my copy of the script. What an idiot I was — and I was a huge fan of Brian's work! In my defence, I was always crazy busy back then.

FD: The Comicraft studio is known throughout the world for high standards of lettering and graphic design, and yet your studio's work is constantly overlooked by the Eisner and Harvey Awards? Does this trouble you at all.

RS: Are we? Well, receiving an award is always nice in recognition for a job well done, but it was much more significant to me that Ladrönn won an Eisner award for his work on the Hip Flask: Mystery City in 2005. As far as awards for lettering are concerned, I do think there's some suspicion about work created with fonts in a studio, and that can never really be dispelled. I think it's a testament to the quality of our fonts when letterers who have bought them — and use them well — are nominated for awards for Best Lettering. All too often, letterers — and colourists — are nominated for an award when they have worked on a title that has collected all the other available awards, for best series, best writing, best art and so forth, so sometimes you win by association I think. What does bother me is that great creators like Dave Sim and Chris Ware are awarded the Eisners and Harveys for Best Lettering — their work is so much more than the lettering, but perhaps it's the only part of the work that judges can identify as significant, so it's kind of like a consolation prize.

I'm also of the opinion that the best lettering is really the lettering that is so much a part of the artwork that you don't really notice it; kinda like not noticing that the sound editing on a film is really good… we only really notice sound editing, foley work or music in a film when it's really bad — or absent perhaps — not when it feels like it's a part of the whole experience. That's my story and I'm sticking to it!