Posted in: Comics | Tagged: dennis o'neil, denny o'neil, how to write comics and graphic novels, How to write comics and graphic novels by Dennis O'Neil

How To Write Comics And Graphic Novels by Dennis O'Neil #23 – Take Notes

He's already written a string of columns in line with his teaching on Bleeding Cool. And now he's writing some more…

Last week, I promised that this week we'd look at what has become the dominant narrative form in comics, and damn near everything else. We're referring to continued stories, here, or serials, or arcs, all of which have pretty much the same meaning. Rather than perpetrate what could be a lengthy riff on the subject, I'll cop out and simply give you my lecture notes for next week.

LONGER STORIES

I. Terra incognita. No one much thought out structure for multi-part

stories.

A. Continuing characters only exist 150 years. First, self-contained stories or short novels.

1. Dime novels.

2. Penny dreadfuls.

B. Serials only since Dickens' time–mid 1800s.

1. First were not really serials. Were novels, cut into chunks.

2. Movie serials since 1912.

a. What Happened to Mary serialized simultaneously in screen and in McClure's Ladies World magazine.

b. The Adventures of Kathlyn released in 1914–first true serial.

c. Perils of Pauline (1914) First biggie. Twenty chapters.

d. Blazing the Overland Trail, 1956, Columbia, last serial ever produced.

REVIEW STRUCTURE FOR LONGER STORIES IN COMICS.

[Arcs and/or miniseries]

No rules, but…

NONRULE 1: HAVE ENOUGH STORY TO FILL THE ALLOTTED NUMBER OF PAGES.

Don't pad or stretch

Melville: To write a mighty book you must have a mighty theme.

NONRULE 2: THERE MUST BE A MAJOR CHANGE, DEVELOPMENT OR REVERSE IN EVERY ISSUE.

Useful to break story into sections.

Example:

Issue 1.Hero learns of/defines problem.

Encounters first opposition.

Issue 2: Hero begins to seek solution. Opposition

intensifies.

Issue 3: Hero finds solution. Opposition

intensfies.

Issue 4: Hero solves problem.

Each must have one turning point/surprise. In each, hero must accomplish something.

End on reason for reader to continue buying series. Usually cliffhanger.

A. End on cliffhanger or unanswered question.

B. Beginning with issue 2–

1. Enough exposition to permit reader to understand immediate

situation.

2. If something hasn't been mentioned for a while, reintroduce.

a. Cf. subplots and evolving plots in normal continuity.

II. Multiple plot approach.

A. Several plots resolved in bits as series progresses. Example: John Ostrander's Gotham Nights.

1. Must have something unifying them

2. Most dramatic resolution at end.

III. Mosaic approach.

Forerunner: Hammet's Dain Curse.

A. Several complete stories that add up to one "mega-story."

B. Several complete stories that set up a final story.

IV. RULE 3: KNOW ENDING WHEN YOU BEGIN.

Always important, most important in this form.

A. Dangers.

1. When you figure out best ending, previous installments too far along to change.

2. Bored readers because material has nothing to do with narrative spine.

NB.: Spine: sequence of events leading to inevitable conclusion.

Movie example: A Bridge Too Far.

Short story example: Perfect Day for Bananafish.

V. Ask yourself: What is series to accomplish?

1. Sometimes there's a goal in addition to entertainment.

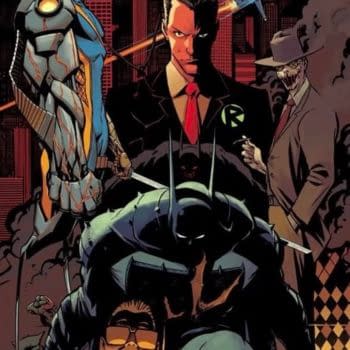

a. Azrael miniseries is an example.

i. Set up something in other continuity.

ii. Intro new character.

b. Similiarly: Seduction of the Gun and Vengeance of Bane

Make readers aware of social problem.

Uberarc Structure

Sense of closure in every episode plus reason to come back,

Most common in TV

Problem hero must solve that continues through season.

But every week smaller problem solved

- TV's Mentalist: find wife's killer

- Similarly: Fugitive

- White Collar

- The Following

- Burn Notice

- Lost

- 24

Comics did it first.

- Iron Man drunk.

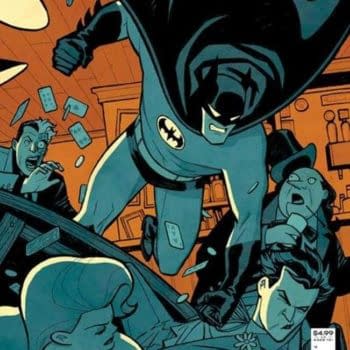

- No Man's Land

- Alan Moore's Swamp Thing

- Superman in Space

- Spider-Man clone

- Thiese are not miniseries–one story continued over several issues.

Levitz model.

Several plots continuing simultaneously.

One ends in every issue and another is introduced.

"B" plot graduates to "A" plot, etc.