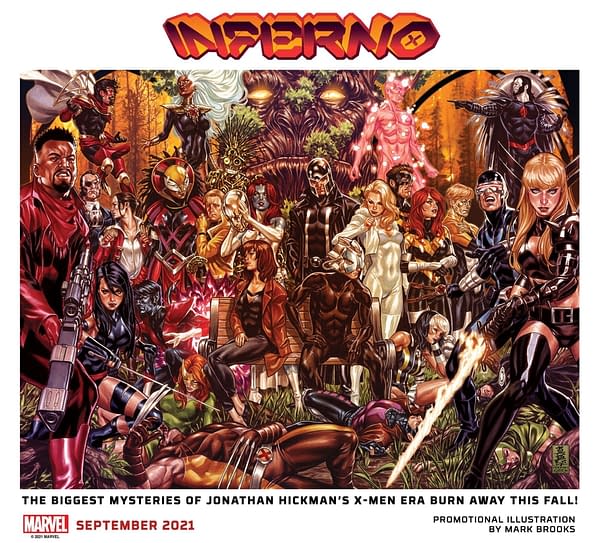

Posted in: Comics, Marvel Comics | Tagged: inferno, jonathan hickman, marvel, x-men, X-ual Healing - The Weekly X-Men Recap Column

On the Illusion of Change and Jonathan Hickman Leaving the X-Men

Is there anything more "comics" than Jonathan Hickman leaving X-Men because nobody — writers, editors, and readers included — is willing to move past the first act of his planned story? In an industry where characters never age, where any significant change, even death, is eventually undone, and where readers must be dragged kicking and screaming toward any form of progress, there's no better metaphor for the business as a whole than a writer planing a three-act story and finding that everyone wants to live indefinitely in the first act. That's comics in a nutshell.

In a 1983 essay lamenting the state of Marvel comics, esteemed comics creator Alan Moore wrote, "You see, somewhere along the line, one of the newer breed of Marvel editors … had come up with one of those incredibly snappy sounding and utterly stupid little pieces of folk-wisdom that some editors seem to like pulling out of the hat from time to time… 'Readers don't want change. Readers only want the illusion of change.' As I said, it sounds perceptive and well-reasoned on first listening. It is also, in my opinion, one of the most specious and retarded theories that it has ever been my misfortune to come across."

A lot could be said about Hickman's X-Men reboot and whether or not it was doomed from the start. Many fans optimistically believed that HoXPoX would kick off an epic story akin to Hickman's run on Fantastic Four. Others, like myself, worried that it would be an overly long, meandering mess like Hickman's Avengers run that ended with the chronically-delayed Secret Wars super-mega-crossover event. What nobody saw coming was that Hickman's X-Men reboot would be more like his run on S.H.I.E.L.D. — full of potential and ideas that, thanks to comically long delays, prevented them from coming to fruition until long after everyone stopped caring.

But that may be too harsh an assessment for Hickman, who, other than the fact that he ought to have known better, isn't really to blame for any of this. One could argue that every period of substantial change in comics is immediately met with an equal reaction of anti-change to restore things to that "iconic" state. Grant Morrison's X-Men run, which turned mutants from a feared and hated minority to the inevitable triumph of evolution with some serious sex kink, was followed up by Astonishing X-Men and the House of M, which reset things back to normal.

"I appreciated that House of X resonated with them to the extent that they didn't want it to end," said Hickman in discussing his departure, "but the reality was that I knew I would be leaving the line early."

And it isn't just the X-Men that suffer from this predicament. J. Michael Straczynski's oft-criticized but undeniably bold run on Spider-Man was so jarring to readers, writers, and publisher accustomed to only the illusion of, and never the actuality of, change, not only ended with an event designed solely to undo one of the character's biggest actual changes, One More Day, but also was immediately followed up by Brand New Day, a nearly year-long initiative involving multiple creators working together to put Spider-Man back in the essential state he was in during the 1980s.

That's not to say that all change is good or that change is inherently a good thing. JMS had his flaws. We all remember Sins Past. But like Chuck Austen's run on X-Men, perennially maligned for its worst parts (She Lies with Angels, The Draco, Havok offering his urine to Iceman to reconstitute his body), it avoided comics only truly unforgivable sins: boredom and stagnation.

"Who says readers don't want change?" Moore asked in that essay almost forty years ago. "Did they do a survey or something? Why wasn't I consulted?"

None of this is to say that the current state of the X-Men comics isn't enjoyable for what it is. But it does lend credence to my original assessment of the whole thing back when it originally started: the style and hype of Grant Morrison's X-Men reboot devoid of the actual revolutionary substance. Unless, of course, you count canonicalizing Wolverine, Cyclops, and Marvel girl in an ongoing three-way sexual relationship and fueling years' worth of articles about Wolverine's penises. I'll always be grateful to Hickman for that one.

To be clear, I'm not upset that Hickman is leaving the X-books or that his X-Men reboot may forever be stuck in second gear. To some extent, the fact that I can read today in middle age stories about the same characters, set in the same universe, that I was reading about as a child is a large part of the appeal of comics to me, and particularly the X-Men. I read the X-Men through thick and thin, through good times and bad, through Claremonts and Lobdells and Liefelds and Simonsons and Morrisons and Austens and Gillens and Brubakers and Bendises and Rosenbergs and Hickmans and everyone in between. If Victor Gischler's X-Men run didn't make me give it up, Gerry Duggan, Tini Howard, and the gang spinning their wheels a bit in Krakoa, which I largely enjoy for what it is (a trashy soap opera populated by the world's horniest mutants), certainly isn't going to do it. But I can see why some readers might take issue with being promised a story with a beginning, middle, and end, and getting only the beginning. To them, I would simply point out: it's comics — you ought to have known what to expect.

A side note on the origin of the phrase "the illusion of change." It's frequently attributed to Stan Lee, including in a 1998 essay by Peter David in Comic Buyer's Guide, but I can't find the actual original source of the quote from Stan Lee. David as well did not appear to be a fan of the concept.

In any case, we'll have to wait and see how things turn out. Maybe Inferno will provide an abridged version of Hickman's original plans for a story, and if it does, that wouldn't necessarily be a bad thing given the man's well-known aversion to brevity. Or maybe he'll return later to finish what he started once the current crop of creators get bored or start their own Substacks. Or maybe we'll have to rely on interviews decades from now to learn what was originally meant to be, and the X-Men will have moved on to several brand-new status-quo-altering reboots by that time, all of which will have been immediately undone as soon as they ended.

But there's no need to worry about that now because there's nothing any of us can do about it. All we can do is continue to enjoy the current state of the X-Men books for what they have now been confirmed to be: the epitome of all of comics' worst, yet simultaneously most beloved, tendencies.